Psoriasis is a common skin condition which affects an estimated 3% of the population. Commonly considered as an adult condition approximately one third of people develop the disease in childhood (Bronckers et al, 2015; Gonzalez et al, 2016; The Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Association, 2019; Primary Care Dermatology Society, 2019). Certainly, Benoit and Hamm (2007) suggest that in one third of cases, psoriasis starts in the first or second decade of life. Juvenile psoriasis is also associated with other comorbidities such as hyperlipidaemia, obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn's disease (Augustin et al, 2010). Understanding this illness means that health-care professionals, such as school nurses can help by providing educators with appropriate information about it, educate those in the classroom and help reduce stigma for any children or young people with the condition (Olson et al, 2004).

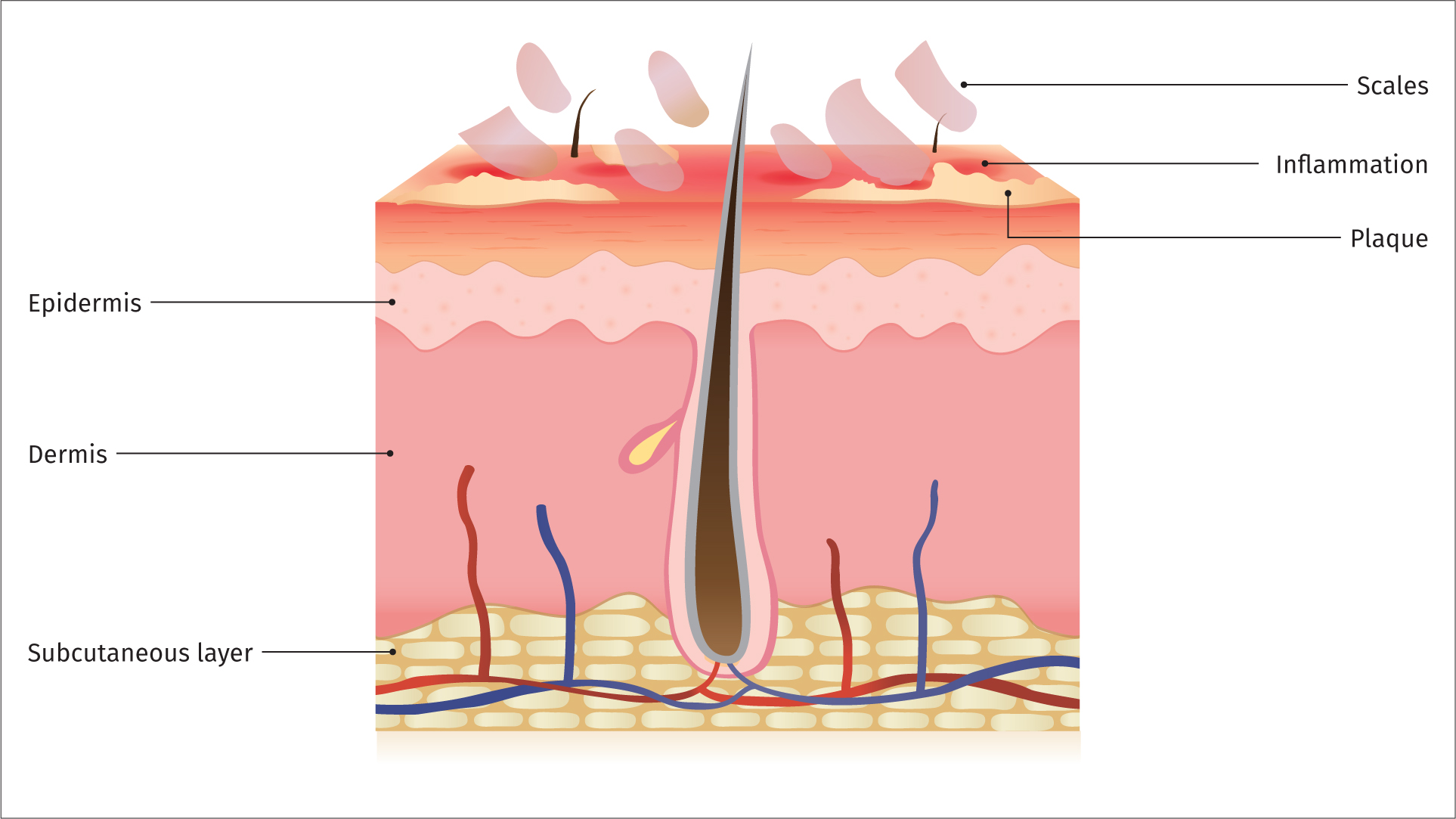

Psoriasis is a chronic, inflammatory immune-mediated disease characterised by red, flaky skin lesions with silvery scales; it characteristically follows a relapsing-remitting course (Bronckers et al, 2015). It typically affects the extensor surfaces on the elbows and knees, the scalp and the trunk. It can, however, also affect the nails and joints (psoriatic arthritis). Associated symptoms include, for example, psoriatic plaques, related secondary infection and persistent itch, as well as stigma (Dawn and Yosipovitch, 2006).

Aetiology and pathophysiology

The aetiology of psoriasis is not fully understood; however, genetic and environmental factors are significant in its development (World Health Organization, 2016). In healthy individuals, skin proliferation takes approximately 28 days, however, in those with psoriasis new skin cells are produced too quickly with a 4-day turnover (Lawton, 2018).

There are several types of psoriasis; with chronic plaque psoriasis the most prevalent in childhood, followed by guttate psoriasis (de Moll et al, 2016). Rogers (2002) suggests that guttate lesions and anogenital and facial involvement are particularly prominent in the childhood age group.

The different types of psoriasis include:

- Chronic plaque psoriasis This is the most prevalent occurring in approximately 80% of patients (NICE, 2017). The typical presentation is of well demarcated red/pink lesions with silvery scales. If scales are scraped or picked off, there is usually pinpoint bleeding, which is known as Auspitz's sign.

- Guttate psoriasis This is the second most prevalent phenotype in children. The presentation is of small, round ‘raindrop’ lesions on the trunk, which become scaly. It may also present following a group A β-haemolytic streptococcus throat infection (Telfer et al, 1992). This subtype tends to be self-limiting; resolving within 3 months. However, in some individuals there may be recurrent attacks or joining together of lesions, which become plaque psoriasis.

- Scalp psoriasis The scalp is a common site for psoriasis presenting with dry flaky well-defined patches, typically just within the hairline and behind the ears. Associated alopecia may occur but almost always resolves spontaneously when the lesion clears.

- Nail psoriasis This affects <5% of patients with psoriasis. Presentation may include nail pitting, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and yellow/red discolouration of the nail bed.

- Flexural psoriasis Flexural psoriasis may affect several sites including axillae, groin, umbilicus, under the breasts, gluteal cleft and the genitals. Presentation is usually symmetrical and may be red with a shiny surface with no scaling due to friction.

- Erythrodermic psoriasis This is a medical emergency as it is potentially life-threatening and specialist assessment is required.

- Pustular psoriasis Pustular psoriasis is a rare form of psoriasis in which there is a dramatic presentation of pustules on a background of tender, inflamed skin. It typically follows an unstable period and the patient may become acutely unwell with fever and malaise.

Management of psoriasis

The goal of treatment is empowerment and control as there is no cure for psoriasis (World Health Organization, 2016; Lawton, 2018). Decisions regarding treatment should be patient-centred, taking into consideration the preferences of the child (dependent on age/understanding) and/or their parents/carers. It is, therefore, important to take into consideration the age of the child or young person when considering treatment choices (Morris, 2002). All children and their parents/caregivers should be offered support and appropriately tailored information to ensure they understand the diagnosis and treatment options, lifestyle risk factors, how to treat their psoriasis including how and when to use prescribed treatments and follow-up arrangements. Any treatment and management plan should be patient-tailored and include physical and psychosocial care (Scharloo et al, 2000; de Jager et al, 2011). Certainly, Evers et al (2016:167) suggest that patients with a dermatological condition often report as having a lowered quality of life, feelings of stigmatisation and shame and that it impacts their psychological welbeing. Psoriasis disease can lead to feelings of disability or psychosocial stigmatisation (Schmid-Ott et al, 2005). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2017) recommends that patients are given strategies to help them cope with the impact of their disease on their physical, psychological and social wellbeing (NICE, 2017).

Topical treatment

Topical treatment is considered as first-line therapy for psoriasis (NICE, 2017). Patient preference, cosmetic acceptability, practical aspects of application, and the site(s) and the extent of psoriasis to be treated need to be considered (NICE, 2017). As most children have a mild form of psoriasis, they can generally treat it effectively with topical agents such as emollients, coal tar, corticosteroids, dithranol and calcipotriol (Dogra and Kaur, 2010; NICE, 2017).

The following are a list of different topical treatment options:

- Emollients—they are effective at moisturising areas of dry and cracked skin, they may have an anti-proliferative effect reducing scaling (Paediatric Formulary Committee, 2019; Primary Care Dermatology Society, 2019).

- Corticosteroids of moderate potency—these may be useful in small areas of flare-ups especially on the face. However, they should be used sparingly and for a limited period, therefore they are not suitable for long-term management of psoriasis.

- Coal tar preparations—these have been used for many years; however, the smell may not be acceptable to children and adolescents.

- Vitamin D treatments—these include calcipotriol and tacalcitol

- Dithranol—a hydroxyanthrone, anthracene derivative that is prescribed for chronic and acute psoriasis. Its mode of action is not fully understood but it has anti-proliferative and anti-inflammatory effects on psoriatic and normal skin (NICE, 2019).

- Tazarotene—a member of the acetylenic class of retinoids, it is approved for treatment of psoriasis (NICE, 2017),

Second-line treatment or third-line treatment options such as phototherapy or systemic therapy may be offered at the same time as topical therapy when topical treatment alone is unlikely to adequately control the psoriasis (NICE, 2017).

‘Decisions regarding treatment should be patient-centred, taking into consideration the preferences of the child (dependent on age/understanding) and/or their parents/carers.’

Phototherapy

Phototherapy is considered second-line therapy and should be offered to patients with plaque or guttate psoriasis not controlled with topical treatments alone (NICE, 2017).

Systemic

Systemic therapies such as methotrexate, ciclosporin, acitretin, adalimumab, entanercept and ustekinumab are considered third-line therapies and should only be initiated within specialist settings following a thorough assessment and having fully explained the risks and benefits to the patient and/or their parents/carers (NICE, 2017).

Comorbidities

The two most prevalent comorbidities are cardiovascular disease and psoriatic arthritis, with approximately 30% of adults with psoriasis subsequently diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis (Tucker, 2018). As with many patients with chronic diseases, quality of life and mental health may be adversely affected in those with psoriasis (de Jager et al, 2011).

TABLE 1. THINGS TO CONSIDER WHEN REVIEWING TREATMENT

Consider the following when reviewing the treatment for any type of psoriasis:

|

Psoriasis is considered as a disfiguring skin disease and may have a profound emotional effect (Raychaudhuri and Gross, 2000). Issues surrounding self-esteem and body image in children and adolescents may give rise to anxiety and depression (Gonzalez et al, 2016; Salman et al, 2018; Todberg et al, 2018).

Salman et al (2018) suggest that the management of this disease consists of time-consuming treatments and the visibility of the lesions can influence a patient's quality of life. We know from previous studies that psoriasis has a negative impact on a child's quality of life (Lewis-Jones and Finlay, 1995). De Jager et al (2011) showed in their pilot study of the effect on quality of life of childhood psoriasis that 65% of children experienced stigmatisation, 71% reported itching, and 43% complained about fatigue. Magin et al (2008) suggest that psoriasis is one of the common diseases and have been consistently associated with adverse psychological sequelae which includes stigmatisation and that children are commonly teased and bullied because of their appearance. Certainly, within the school setting, problems with self-esteem and participation may arise during several activities such as PE lessons and exposure of large areas of skin in swimming activities (Bronckers et al, 2015).

School nurses have a key role in providing education about the condition to the individual and their family. Self-management including recognition of potential flare-ups can support empowerment (de Moll et al, 2016). Nurses also need to have an understanding of how their patients cope with this stigmatising condition so that they can deliver comprehensive individualised patient care (Joachim and Acorn, 2000). Good communication between the child, parents and the school, including the school nurse, may also enable better management of potential problems (Renton, 2013; Van Onselen, 2013). Ultimately the child should be encouraged and enabled to take part in all activities, especially those they enjoy. Certainly, we know from previous studies that psoriasis may even affect their education, social relationships, family life and future career choice (Kimball et al, 2005). The school nurse can educate children, young people and their families about their general skincare, joint care and the use of topical treatments to manage the condition (Renton, 2013; Van Onselen, 2013).

Conclusions

The prevalence of psoriasis is increasing worldwide, therefore, the more informed health-care professionals are in the assessment of the individual holistically and the management options available for their treatment, the better we will be able to educate, support and advise them on psoriasis (World Health Organization, 2016). Social stigma of psoriasis and its associated impact on self-esteem in children and adolescents has the potential to lead to a greater increase in mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression; school nurses are ideally placed within this age range to offer holistic care and support to children and adolescents suffering from psoriasis and help them effectively manage their condition (Renton, 2013).

REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- What are the co-morbidities associated with juvenile psoraisis?

- Did any surprsie you?

- Will this lead to a change in practice and what will that be?

- Can you summarise the goals of treatment?