Adolescence is a critical period of development within childhood, where young people experience a range of biological, psychological, and sociological changes (Coleman, 2011). During this exciting transition young people develop a sense of self and identity, as well as new peer and romantic relationships (Littler, 2020). However, it is also a challenging period during which they may develop long-term health conditions and may be exposed to a range of risks within the wider social context (Viner, 2013) such as child sexual exploitation; self-harm, suicide, cyber-bullying, peer-on-peer abuse, gang violence (Sidebotham et al, 2016). Hence, it is of no surprise that the second highest safeguarding risks are seen within the adolescent life-course (Brandon et al, 2012).

Adolescent safeguarding is a public health issue that requires a transdisciplinary approach through partnership working between a range of professionals who support young people in practice such as nursing, policing, social work, education, and youth work (Littler, 2020). However, over the last decade, concerns have been raised about the ‘shortcomings of the current UK child protection system in identifying and responding to these risks’ (Peace and Atkinson, 2019: 3). Furthermore, safeguarding reviews (Munro, 2011; HM Government, 2018) have continually emphasised the importance of providing high-quality safeguarding education, as professionals report undergraduate education being inadequate in preparing them for their role in practice (Morgan and Spargo, 2018; Littler, 2019). This is essential to ensure professionals acquire and maintain the right knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values for safeguarding in practice (McGarry et al, 2015).

Introduction

Adolescent safeguarding education has been a key area of interest for the researcher over the last 4 years, this started in their first research study with learners on a children's pre-registration nursing programme which explored perceptions, experiences, and opinions of safeguarding education within their professional training (Littler, 2018). Two of the core categories within this study highlighted the importance of practice education in supporting learners' preparation for practice through case studies and scenarios and the need to understand multiprofessional roles and responsibilities.

The role of the school nurse in safeguarding adolescents was the focus of the second study (Littler, 2019), which magnified the disparity in adolescent development education provided to pre-registration nurses (across all fields of practice) in England. Furthermore, it emphasised adolescent safeguarding as accounting for many of the safeguarding concerns seen by school nurses in the role in practice (Littler, 2019).

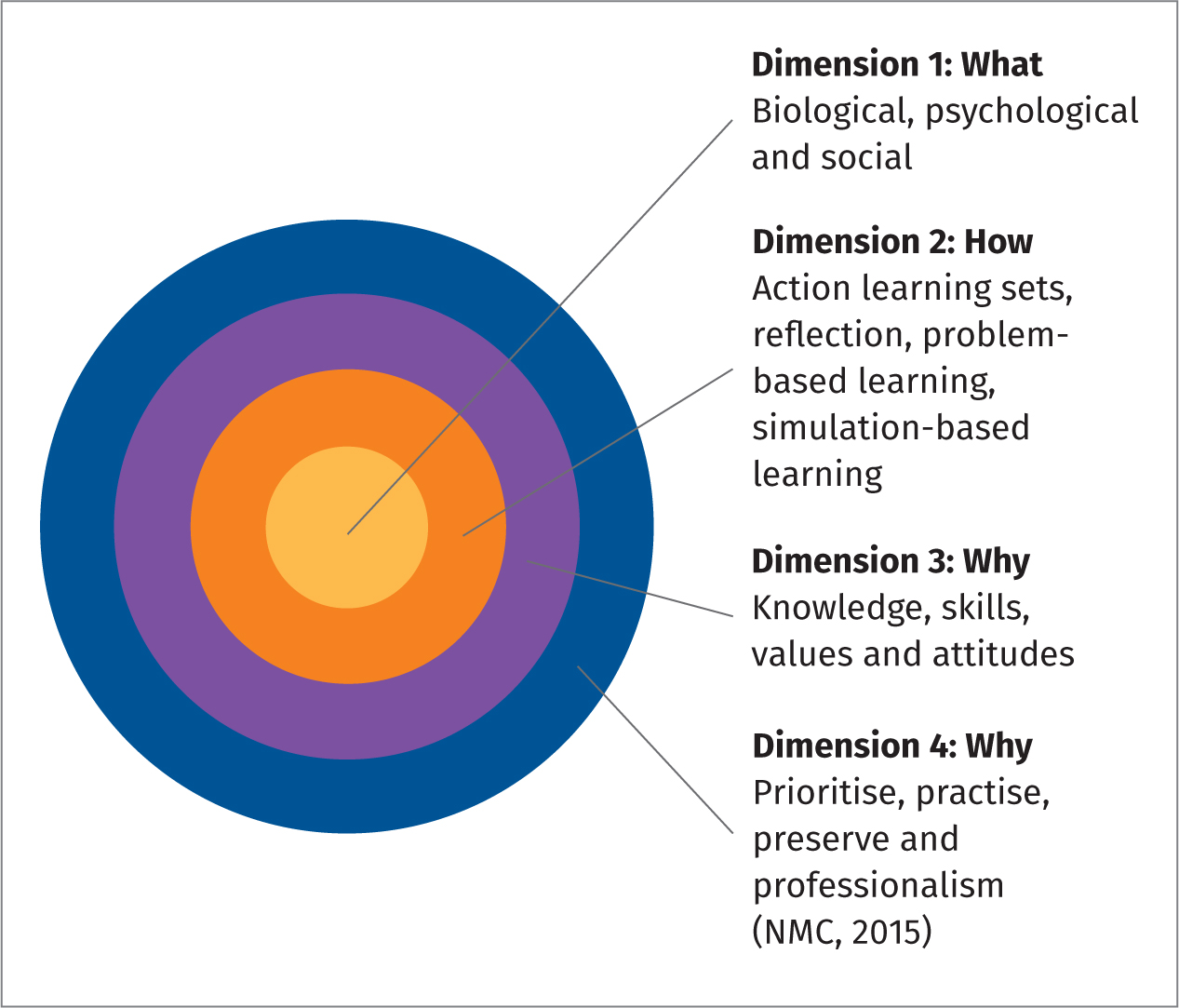

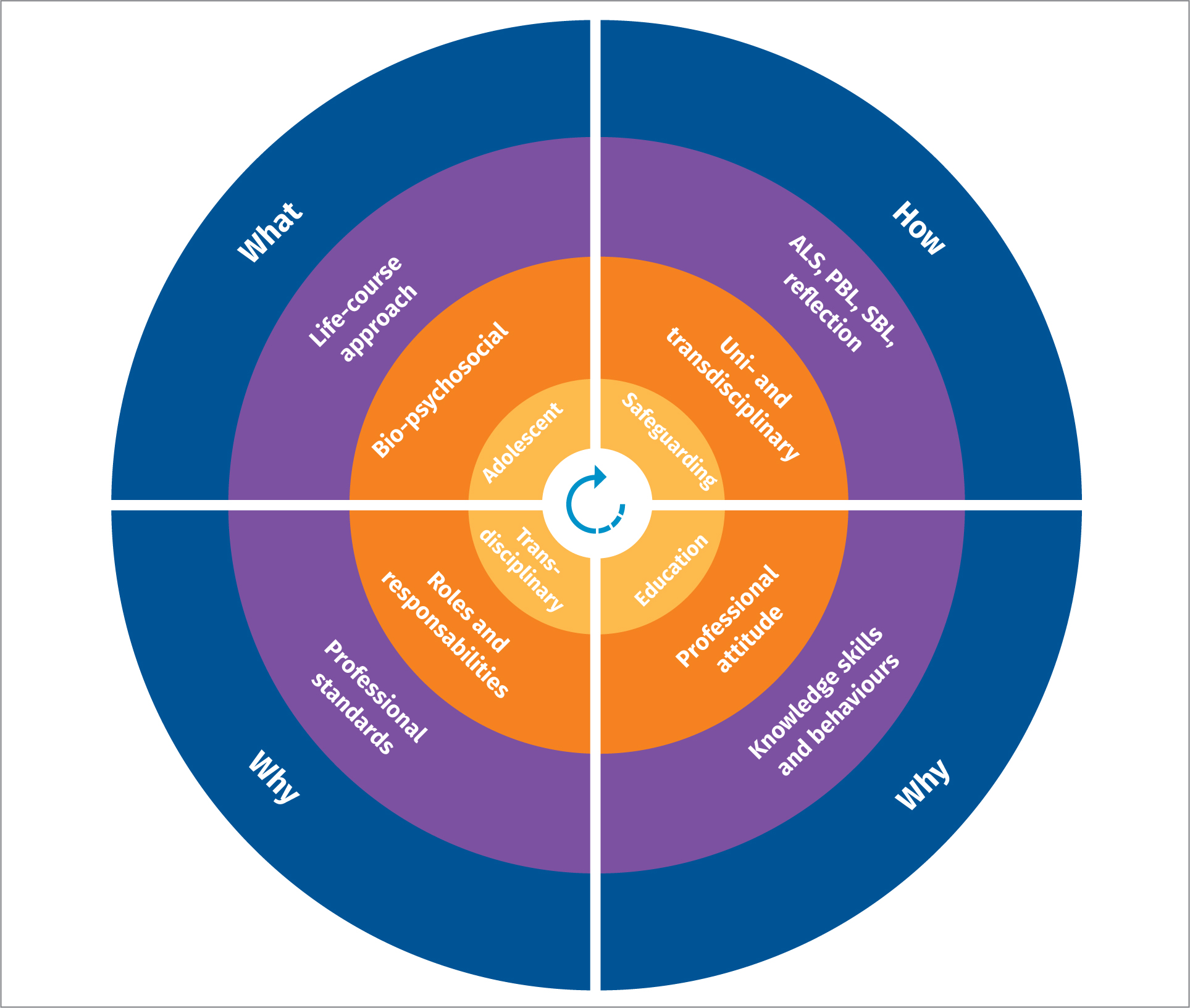

Finally, this led to the design of an adolescent safeguarding curriculum framework for pre-registration nursing (Figure 1), the aim of which was not to be prescriptive, but to support nurse educators with an outline and structure when designing or reviewing new curricula (Littler, 2020). While, the curriculum framework has been designed for pre-registration nursing, the researcher wanted to explore the need for transdisciplinary adolescent safeguarding education across all professional programmes.

Aims

‘Transdisciplinary education is an approach to curriculum integration which dissolves the boundaries between conventional disciplines and organises teaching and learning around the construction of meaning in the context of real-world problems’ (International Bureau of Education [IBE]/United Nations educational, scientific and cultural organisation [UNESCO], 2021). The aim of this research study is to explore the need for transdisciplinary safeguarding education by obtaining feedback on the adolescent safeguarding curriculum framework designed for pre-registration nursing (Littler, 2020). The original framework was designed to raise awareness of the adolescent life-course (stages of development), to align safeguarding education to training (Royal College of Nursing [RCN], 2019) and to reduce the gap between theory and practice to support professionals' role in safeguarding young people (Littler, 2020). Therefore, the purpose of this study is to continue to design and develop an adolescent safeguarding curriculum framework which can be adopted across a range of transdisciplinary professional programmes.

Methods

A qualitative descriptive research design was chosen for this study as it ‘seeks to discover and understand a phenomenon, a process or the perspectives and worldviews of the people involved’ (Merriam, 1998:11). This flexible approach was essential due to the challenges with undertaking research during the coronavirus pandemic in 2021, as this enabled data collection and analysis to be an iterative process by responding to and simultaneously adapting to new insights as the study progressed (Patterson and Morin, 2012). A purposive sampling technique was employed to identify and select individuals or groups that have knowledge and experience in the phenomenon of interest (Cresswell and Plano Clark, 2011). Therefore, the inclusion criteria for this study incorporated participants who were learners (studying) or educators (teaching) on any of the following programmes: nursing, social work, policing, youth work and teaching at an undergraduate (years 1, 2, or 3), apprenticeship or postgraduate level at a university in the North-West of England.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was requested and granted from the researcher's university ethics committee. After receiving this the researcher disseminated the study flyer to a range of sources, which included programme leaders who added this onto their virtual learning environments (blackboard) programme/module sites. This was also advertised on the university communications news webpage and newsletter. Prior to contributing to this research, participants were provided with a study information sheet and consent form, before deciding if they wish to give informed consent to take part. Participants were advised within the information sheet and consent form that taking part was voluntary and that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time, without giving a reason to do so.

Data collection

A combination of data collection methods (online survey and informal interviews) was utilised in this qualitative descriptive research study. Participants who expressed interest and consented to take part in the study were sent a link to access the webinar video, which provided an overview of the adolescent safeguarding curriculum framework. After which they were asked to complete the online survey consisting of 13 open and closed questions. These had been piloted in a previous research study (Littler, 2018) and were based upon obtaining feedback on the original adolescent safeguarding curricula (Littler, 2020).

Aligned to this, informal interviews were used to triangulate data, often an underused method in qualitative research to capture the first-hand experience and exploration of participants within a particular social or cultural setting (Atkinson et al, 2007: 4). Field notes from informal interviews were made during and soon after they were held, which incorporated information such as a summary of notes from the interview, as well as the researchers' reflections and interpretations. The informal interviews were not recorded, due to this detracting from the natural conversation, which would create a more formal data collection process (Swain and Spire, 2020). The researcher ‘summarised the data collected from the interview at the end to determine with the participant if their summaries reflected their views and experiences’ (Harper and Cole, 2012: 2).

Confidentiality was maintained by providing unique identification numbers for each participant survey response and written field notes, which were protected and stored by a password-protected encrypted file stored on the researcher's university OneDrive (General Data Protection Rules [GDPR], 2018). The data was only accessed by the researcher during and prior to the data being destroyed, within 3 months of the completion of the study.

Data analysis

The chosen data analysis method for this study was thematic analysis to identify, analyse and report patterns and themes within the data (Braun and Clarke 2006:16). This involved analysing the data through completing the following six phases: familiarisation with the collected data, generation of initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining, and naming themes and presenting and discussing findings (Braun and Clarke, 2006: 16).

Findings

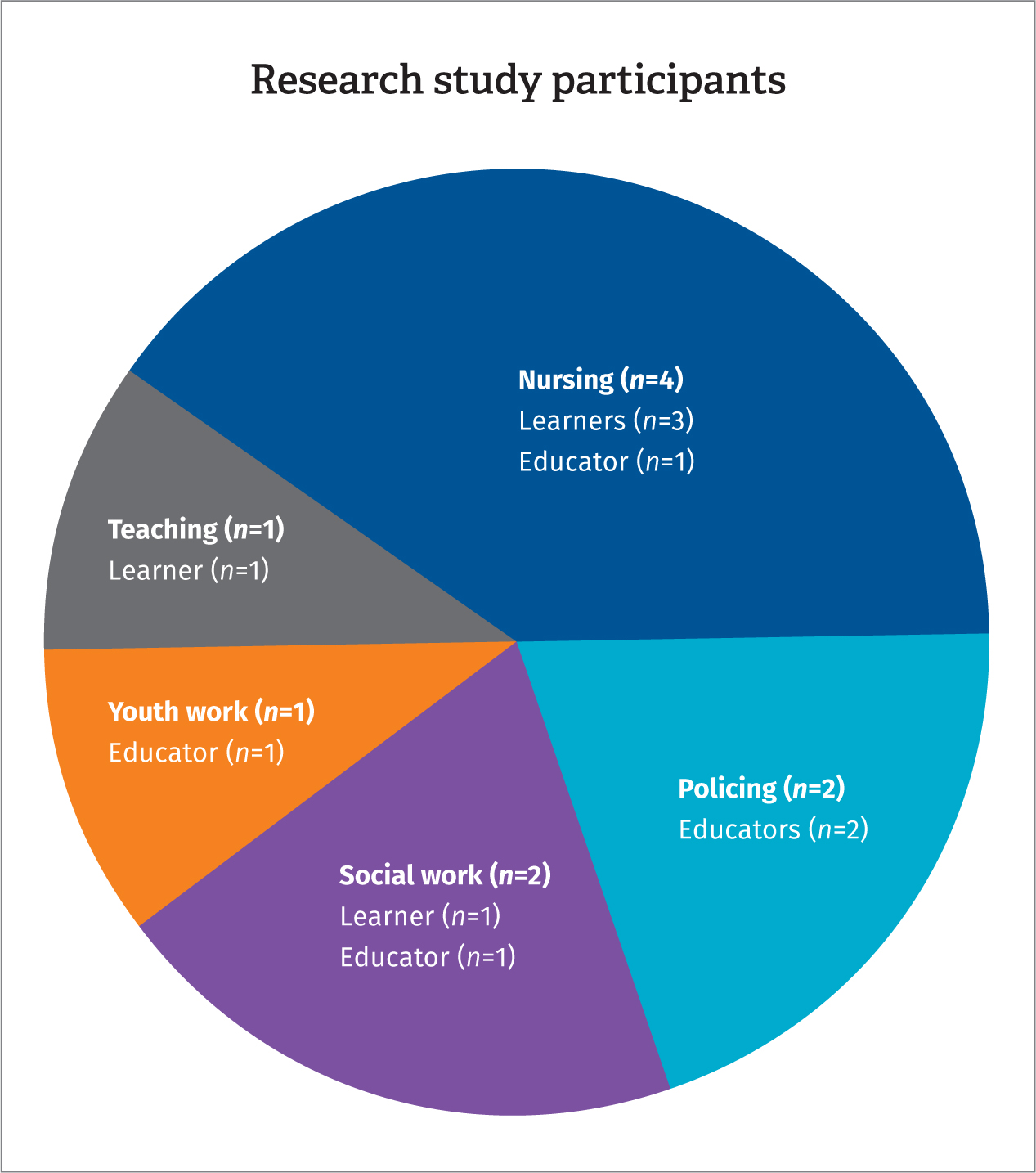

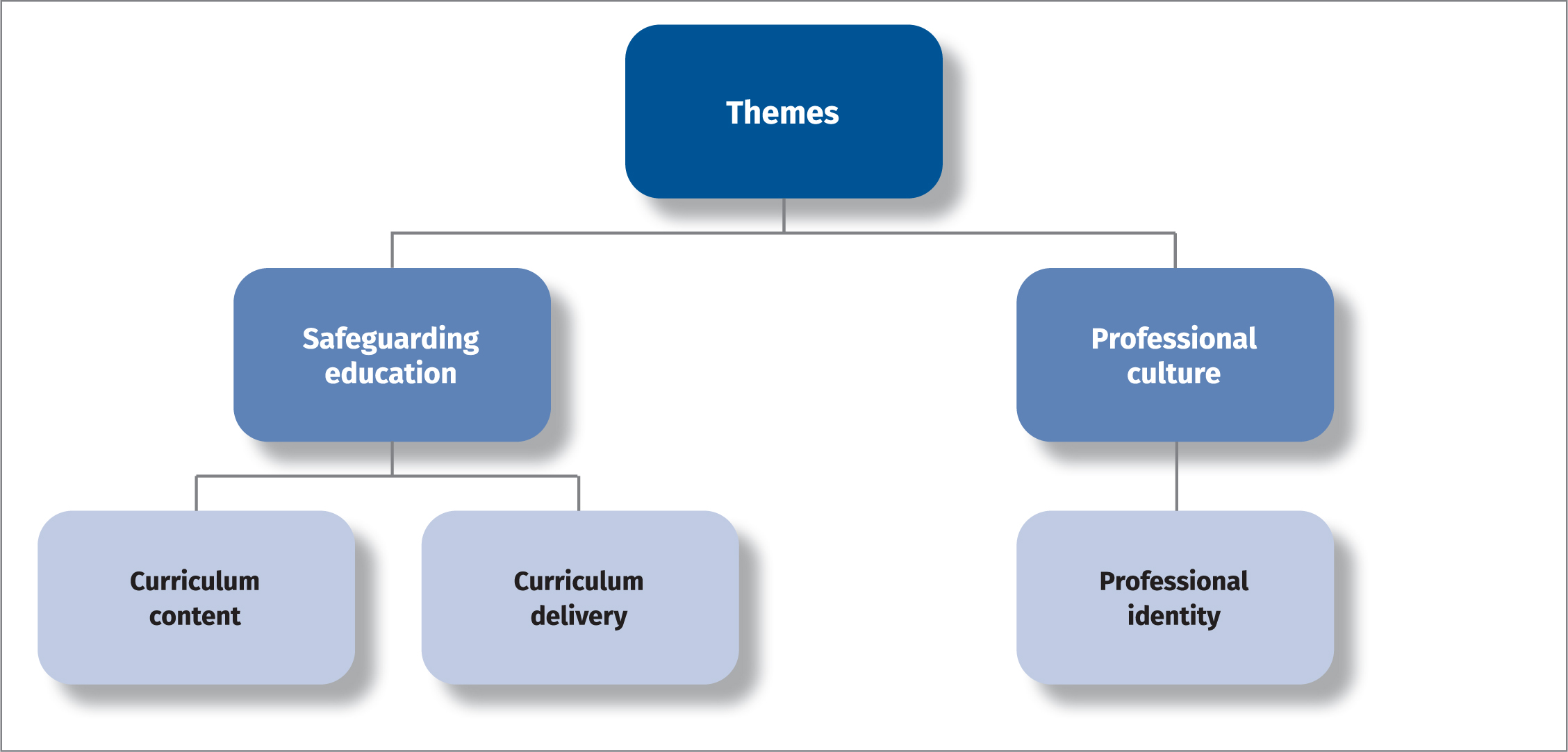

Overall, there were 10 participants who took part in the study, they were distributed as follows among the different disciplines: nursing (n=4), social work (n=2), youth work (n=1), policing (n=2) and teaching (n=1) learners and educators (Figure 2). After completing a thematic analysis of the online survey responses and informal interviews, two key themes were identified (safeguarding education and professional culture) and three subthemes (curriculum content, curriculum delivery and professional identity) (Figure 3).

Safeguarding education

Safeguarding is an overarching framework which encompasses the following key elements (HM Government, 2018: 6):

- Protecting children and young people from maltreatment

- Preventing impairment of children and young people's health or development

- Ensuring children and young people grow up in circumstances consistent with the provision of safe and effective care

- Taking action to enable all children and young people to have the best outcomes.

Curriculum content

Five participants identified the need to incorporate a broad overview of safeguarding within the adolescent safeguarding curriculum framework, which will provide the foundation for specific adolescent safeguarding issues. This includes incorporating the impact of safeguarding within the wider social context such as different levels of risk young people are exposed to, family safeguarding issues, intersectionality relating to race, gender, sexuality, and class and

‘issues of consent and deprivation of liberties’.

(Participant 7)

Parallel to this, there needs to be a clear distinction between safeguarding and protection, as the latter is just one facet of safeguarding that often focuses heavily on policies and procedures. However, it aligns to safeguarding training, which is used interchangeably with education (Lines et al, 2016). Both have distinct functions; safeguarding education focuses on the theoretical foundations of safeguarding practice, whereas safeguarding training focuses on the operational aspects of safeguarding such as policies and procedures (Lines et al, 2016). There is no single piece of legislation, rather a myriad of laws and guidance for safeguarding (NSPCC, 2012: 1). Therefore, safeguarding education should focus on providing an overview of the legislative framework (Children's Act 1989 and 2004) to provide the theoretical foundation.

‘ensures professionals understand the procedures required under legislation’.

(Participant 2)

‘Safeguarding legislation and procedures ie before a case conference there would need to be a strategy meeting’.

(Participant 2)

‘difficult to make decisions when the individual turned 16 as a lot changed in terms of consent, right to information, sharing information’.

(Participant 10)

All participants (n=10) within this study agreed that there is a need to develop adolescent safeguarding education for professional programmes such as nursing, policing, youth work, social work, and teaching. A life-course approach focuses on each stage of development within adolescence, which contains three stages (early adolescence, late adolescence and young adulthood) (Patton et al, 2016). There were (n=2) participants who felt the focus should be on situational safeguarding rather than age related and (n=8) participants agreed a life-course approach was required to support understanding of this key transition.

‘adolescents are seen in a biological sense…as young people may not be as emotionally or physically developed as others and may slip through the net.’

(Participant 6)

‘understanding brain development.’

(Participant 9)

‘theoretical underpinnings are important to understand the age range’.

(Participant 7)

‘Confusion and blurred lines between what is allowed/appropriate for children versus adults, as adolescents seem to lie somewhere in the middle’.

(Participant 10)

There were several adolescent safeguarding topics identified as requiring further education within professional programmes, this includes (n=2) participants who recognised the need for:

‘more emphasis and learning on technology-based concerns, social media and young people out at night/anti-social behaviour.’

(Participant 1)

Other safeguarding topics and risks identified for education within professional programmes to support practice includes:

‘gender stereotypes – particularly abuse against male's beliefs/religious beliefs that can manifest into extremist groups/hate crime/grooming.’

(Participant 6)

‘County lines and child sexual exploitation…there needs to be more recognition of these risks and an understanding to not criminalise young people.’

(Participant 2)

‘frequent safeguarding issues seen in young people… eating disorders, suicidal ideation and self-harm.’

(Participant 6)

‘The effects COVID-19 is having on safeguarding young adults.’

(Participant 1)

Curriculum delivery

Participants were asked about the curriculum delivery to determine whether adolescent safeguarding education should have a uniprofessional, transdisciplinary or a hybrid (combined) approach. All (n=10) participants identified the need to incorporate a hybrid approach to education within professional programmes as:

‘I think that there should be more training and awareness of the importance of working in partnership with others’.

(Participant 6)

‘Bringing different courses together to carry out scenarios, so they have different experiences and can meet new people in the sector before qualified, network/support system for learning.’

(Participant 1)

In addition to this, an example of a series of adolescent safeguarding education workshops were provided for the proposed curriculum, to obtain feedback from all participants in this study on the teaching and learning strategies used. Overall, eight participants identified that they would like the following teaching and learning strategies utilised within safeguarding workshops: classroom-based learning (face-to-face theory), problem/inquiry-based learning, action learning sets, simulation/role play and reflection. However, only two participants would like to include blended learning (combination of face-to-face and online workshops).

Overall, the face-to-face workshops were welcomed as a format for safeguarding education delivery as:

‘not all the information is given at once, so the session can be more realistic and engage the students in different communication skills.’

(Participant 1)

‘a good idea which brings individuals together… sharing from each other’.

(Participant 7)

‘the idea of multi-disciplinary teams and mock case conference.’

(Participant 2)

Another key theme identified within the data, relates to disclosure, participants (n=4) highlighted how safeguarding education should include ‘what to do when a disclosure is made in practice’, which incorporates support for the young person making the disclosure and the professional who has been informed.

‘Some form of education in what to say to children in certain situations to give advice. Role-playing so to speak would, I think be very beneficial. I am not always sure what to say to a child, use their words’.

(Participant 9)

‘Communication with young people who make disclosures could be included.’

(Participant 2)

Professional culture

Another key theme that emerged from the findings was related to professional culture, as (n=4) participants from the study identified this as being a key reason for incorporating transdisciplinary learning within safeguarding education. Practitioners' ideas, values, attitudes, beliefs, and perspectives are socially constructed which characterise their professional group (Pivaty, 2019). Consequently, this can result in different professional and legal powers, approaches, and assessment of risk in safeguarding, therefore it is essential that we:

‘Share information and knowledge between different sectors and services to learn from each other.’

(Participant 6)

Professional identity

The importance of professional identity, also emerged through the data, as two participants identified this as an area of consideration for future safeguarding education. We need to ‘recognise how learners’ own beliefs, experience and attitudes might influence professional involvement in safeguarding (RCN, 2019: 25). As four participants identified, the key role of professionals in safeguarding involves developing therapeutic relationships with young people in practice, so that this empowers them by ensuring they are supported and confident in making their own decisions and in managing risk.

‘Consent, boundaries, building relationships and ensuring they are therapeutic.’

(Participant 10)

Limitations

There were limitations within this study, such as the fact that just 10 participants were recruited to the study. This meant that for some of the disciplines there was only one participant, such as youth work (n=1 educator) and teaching (n=1 learner), all of which were from one university in the North-West of England. However, despite this, the study produced rich data and consequently closed early due to no new information coming through, thus the researcher felt assured that if further data collection had continued, it would have yielded similar results (Faulkner and Trotter, 2017: 1).

Discussion

In this research study, the aim was to explore the need for safeguarding education within transdisciplinary professional programmes. Participants were asked to provide feedback on the design of an adolescent safeguarding curriculum framework which had been designed for nursing (Littler, 2020). The curriculum framework was based upon Skeketee et al's (2014) four-dimensional interprofessional education model, which looks at the following four dimensions:

- Future orientation of health practice

- Knowledge, competencies and capabilities

- Teaching, learning and assessment

- Institutional delivery.

There were two key themes identified within the data, these were safeguarding education and professional culture. The first theme aligns to dimensions one, three and four of Skeketee et al's (2014) curriculum framework model as it is based upon education content and delivery. Participants identified the need for adolescent safeguarding education within a range of professional programmes such as nursing, policing, youth work, teaching and social work. The importance of incorporating a range of broader overarching safeguarding subject areas such as consent, legislation, intersectionality, levels of risk and specific safeguarding topics such as technology-based concerns/social media were identified. Aligned to this, the need to adopt a life-course approach to adolescent safeguarding education was highlighted in this study, which aligns to transitional safeguarding where the focus is on safeguarding adolescents and young adults across developmental stages (Holmes, 2021).

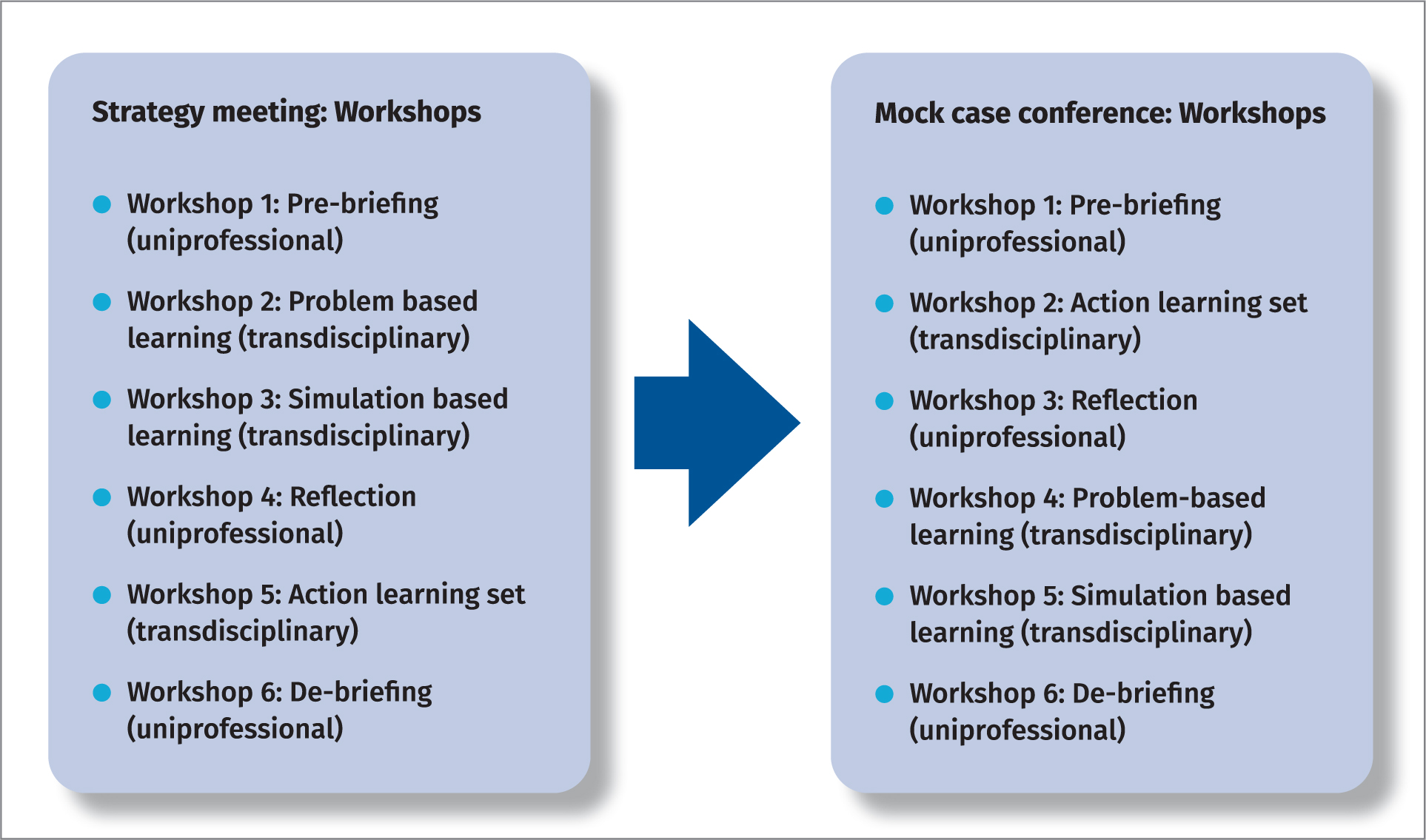

All participants in this study recognised the need for a hybrid approach to safeguarding education through both uniprofessional and transdisciplinary workshops which would be underpinned by experiential learning (Kolb, 1984) and social constructivism (Vygotsky, 1978) as the teaching and learning theories to support the strategies used to deliver education. Participants highlighted they would like to see the following strategies: face-to-face, reflection, action learning sets, problem-based and simulation-based learning. This will support safeguarding education delivery through transdisciplinary learning in specific safeguarding areas such as strategy meetings, mock case conferences and role play and scenario-based exercises for example, when a young person makes a disclosure. As the aim of transdisciplinary learning is to foster relationships, interdependence, collaboration, while enhancing the contribution of each discipline in the learning environment (Tsimane and Downing, 2019: 95).

In dimension two of Skeketee et al's (2014) curriculum framework model, the focus is based upon developing knowledge, skills, and behaviours, which is underpinned by the professional standards and code of conduct for each discipline. This is parallel to the second theme of this study – professional culture, which focuses on ‘the values, ceremonies and ways of life characteristic of a given group’ (Giddens, 2006: 1012). Hence, as part of designing the transdisciplinary adolescent safeguarding curriculum framework, pre-briefing and debriefing workshops have been incorporated at the beginning and end of each phase of the strategy and case conference workshops, to support expectations, ground rules, self-analysis, and reflection in and on action (Schon, 1991) (Figure 4) as learning continues after the debriefing (Dekker et al, 2013).

Overall, through undertaking this research study, the adolescent safeguarding curriculum framework designed for pre-registration nursing (Littler, 2019) has been developed and extended further to incorporate these findings which can be used as an outline and structure for a range of transdisciplinary programmes (Figure 5). A recommendation from this study is that this curriculum framework is adopted for other transdisciplinary programmes from other universities across England. Furthermore, another recommendation from this study, aligns to a recommendation made in Littler (2020), that both intercollegiate documents (RCN, 2018; 2019) should be a single document to incorporate adolescence and a life-course approach and be extended to incorporate all professions working with young people in line with the ‘working together to safeguarding children’ guidance (HM Government, 2018).

Conclusions

This study explored the need to incorporate adolescent safeguarding education with participants at a North-West University in England, who were either studying or teaching on one of the following transdisciplinary programmes: nursing, youth work, policing, social work and teaching. Findings from the data collected, highlighted the importance of adolescent safeguarding education that adopts a life-course approach. Furthermore, it has been found that further education is required on technology-based safeguarding issues, and what to do when a disclosure has been made, for both professionals and young people. The key takeaway message from this study is that learners and educators recognised the value of learning with other disciplines, therefore recommending a hybrid model of delivery (uniprofessional and transdisciplinary) within adolescent safeguarding education.

KEY POINTS

- Safeguarding education should incorporate a life-course approach, in this study the focus has been on adolescence.

- To encourage transdisciplinary working, a hybrid approach (uniprofessional and transdisciplinary) should be adopted to support the delivery of safeguarding education across a range of transdisciplinary professional programmes.

- There is a need to utilise a range of teaching and learning strategies to support application to practice through action learning sets, reflection and problem and simulation-based learning through role play.

- Safeguarding education workshops should incorporate pre-briefing and debriefing workshops to support pre- and post-learning.

REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- Why should adolescent safeguarding education be delivered transdisciplinary?

- How can school nurses work collaboratively with other professionals working with young people?

- What have you learned by reading this research article?