It is estimated that cardiovascular events are the third cause of death in the world (Berdowski et al, 2010), with about 420 000 out of hospital cardiac arrests occurring in the USA and 275 000 cross Europe each year (Atwood et al, 2005; Go et al, 2014).

Although most cardiac arrests occur at home, a considerable number still take place in public places (Berdowski et al, 2013; Marijon et al, 2015) where the intervention of a member of the public trained in basic life-support (BLS) could potentially make the difference (Sanghavi et al, 2015). However, from all these witnessed arrests, only in a third BLS manoeuvres have taken place with many others having to wait for the arrival of the emergency services (López et al, 2018).

In the case of a cardiac arrest, the human body can survive for only 3–5 minutes without any consequences. However, on average, pre-hospital emergency services of any kind will usually take no less than 8–10 minutes to arrive at the scene, depending on the country, emergency system, location of the event, etc. (Böttiger, 2015).

For this reason, it is generally agreed and scientifically proven that the most important measure to increase the chances of survival with minor or no neurological consequences is the immediate (or as quick as possible) start of BLS manoeuvres (Böttiger, 2015) by a member of the public that is properly trained and able to provide immediate support to the victim.

It is therefore generally accepted by all the main health organisations dedicated to this topic that increasing the number of potential public members that could intervene if necessary will lead to an increase in the survival rate in case of cardiac arrest (Dîrzu et al, 2018). To achieve this goal offering effective training courses to as many individuals as possible, on a large scale and at a low cost, is recommended (Beck et al, 2015). Schools are by nature one of the ideal places for implementing this type of large-scale training programmes (Finn et al, 2015).

The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) recommends that BLS training and familiarisation with an external automatic defibrillator should be an essential part of all curricula for secondary schools (Cave et al, 2011). Moreover, the World Health Organization (WHO) offered its endorsement to a document from the European Council of Resuscitation ‘Kids Save Lives’ where increasing the number of trained children in BLS within the school environment is highly recommended (Böttiger et al, 2015).

‘Cardiac-respiratory arrests secondary to a cardiovascular event are still common and […] the implementation of BLS manoeuvres as quickly as possible followed by ADE are fundamental to increase survival chances and to improve the quality of life in case of cardiac arrest…’

In spite of these recommendations, across Europe one can find considerable differences in terms of programme reach, methodologies, type of trainers and time dedicated to the BLS training in schools (Salciccioli et al, 2017).

While in countries such as Norway this training has been part of the curricula in schools for many years, in other countries like Spain or the United Kingdom, even though it is recommended to be included in the annual school plan, in reality, for various reasons these have not been effectively implemented (Miró et al, 2008; Real Decreto, 2014).

In Portugal, although a BLS programme is not regulated by law, the government created the National School Health Programme (PNSE) in 2015 with the goal of having 10% of their teachers and other school employees competent in first aid/basic life support by 2016, a percentage which should increase to 20% by 2020. However, according to the health institute in charge of the programme (INEM), only a small minority of school professionals (569 out of 140 000 in total) had had any kind of training by the end of 2018 (Capucho, 2018).

It is therefore fundamental to increase awareness regarding the importance of BLS and to provide training to all members of the school community (from students to teaching and non-teaching staff (Böttiger et al, 2017). With such training programmes in place, the number of members of the public competent in BLS and able to act in case of need would increase quite significantly in all parts of the country, wherever schools are present (Wissenberg et al, 2013).

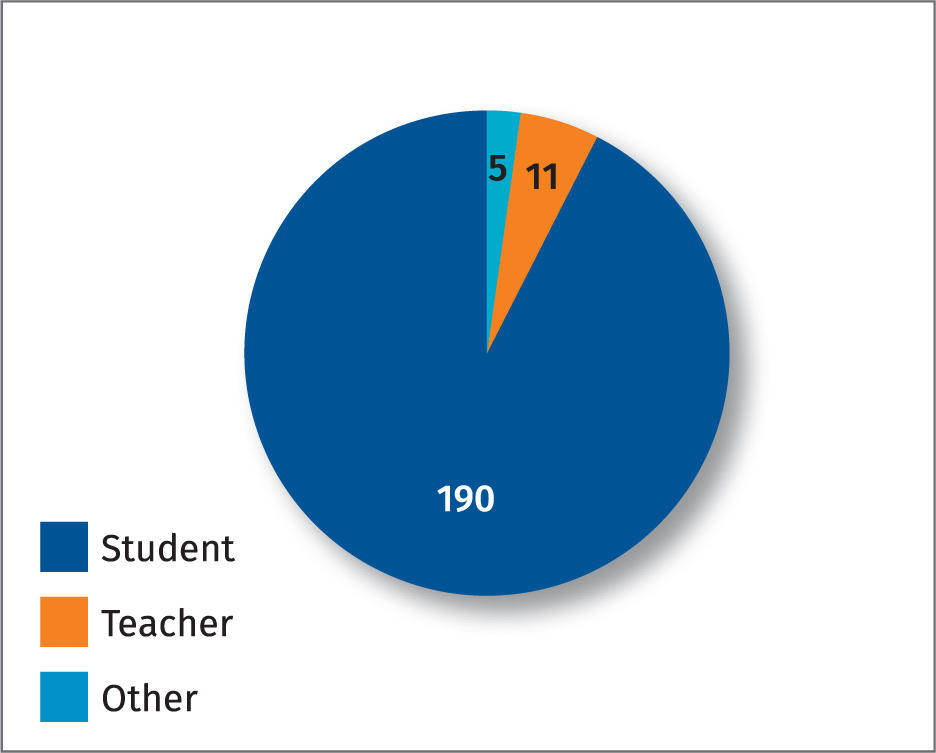

Figure 1. Distribution of trainees by ‘category’

Figure 1. Distribution of trainees by ‘category’

Methods

In the context of the European programme World Restart a Heart Day (European Resuscitation Council, 2019), a team of three nurses and two non-health professionals, present for logistic support, have organised in conjunction with a team of teachers from a secondary school in Porto, a day of briefing and training sessions in BLS for students, teachers and non-teaching staff (sign language translators, school assistants).

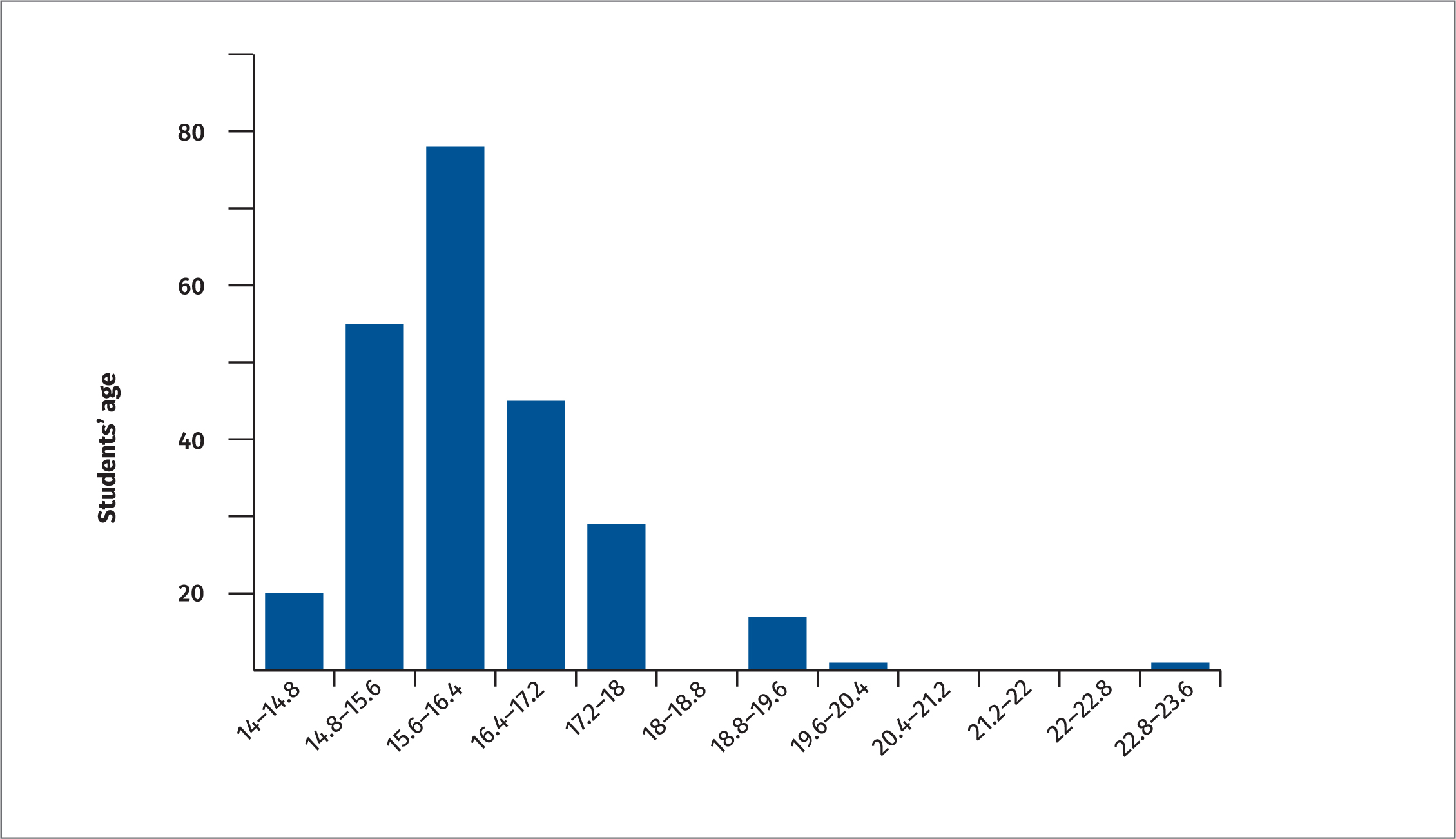

Figure 2. Distribution of students by age

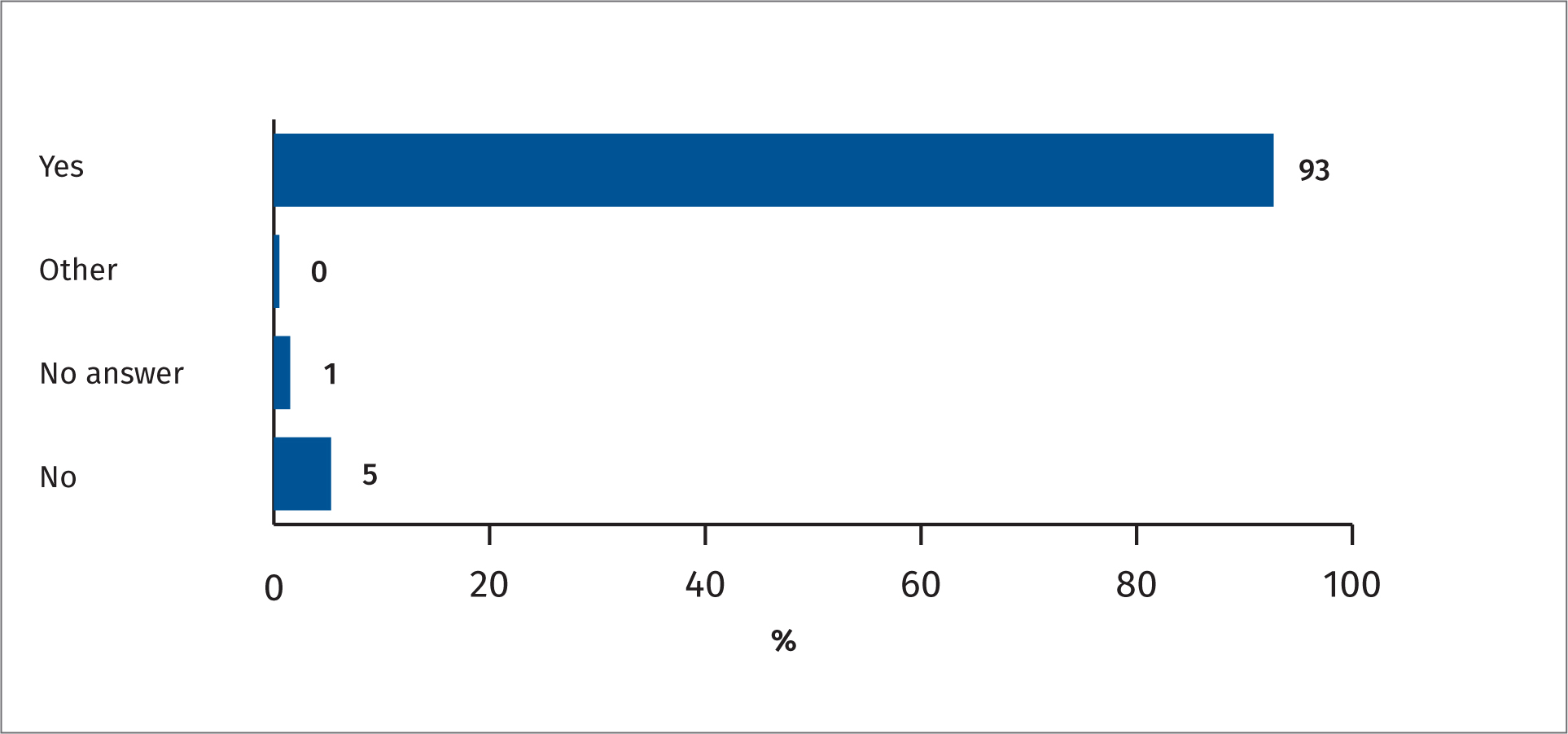

Figure 2. Distribution of students by age  Figure 3. Had you heard about BLS before today?

Figure 3. Had you heard about BLS before today?

A total of 206 individuals, divided in classes of 7 to 20 participants, had access to a short theoretical session with the support of a PowerPoint presentation conducted by a certified trainer in BLS, with the following topics discussed: definition and causes of out of hospital cardiac arrest, the importance of calling for help and starting immediate BLS, the chain of survival and its theoretical basis.

Each session was then followed by a practical presentation following the four steps method:

- See

- See and listen

- See and explain

- Do.

Each group was then divided into smaller groups where the three nurses with the assistance of two BLS mannequins would support students during their own training in BLS.

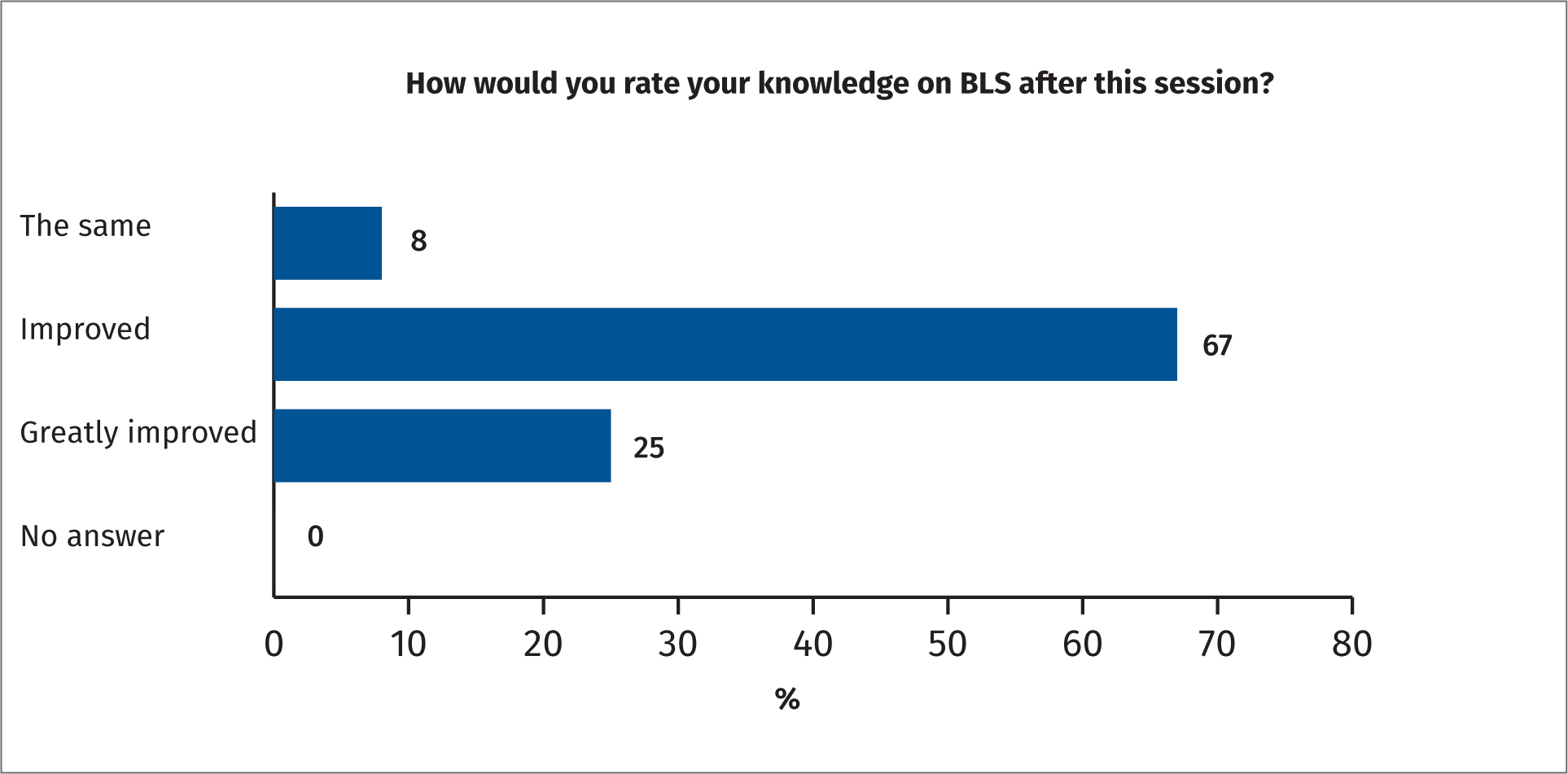

Figure 4. Knowledge on the topic after the session

Figure 4. Knowledge on the topic after the session

Each session lasted about 40 minutes, divided in 10 minutes for the theoretical presentation and answering questions and the last 30 minutes for the individual practice in groups where each student was able to practice all the BLS steps and perform cardiac compression manoeuvres at least twice. Within the smaller groups, there was the chance for the students to ask questions or share their experience with colleagues and the trainer. The students were also encouraged to work in teams and to pay attention to the context given by the trainer – cardiac pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in school, at home or in the street, for example.

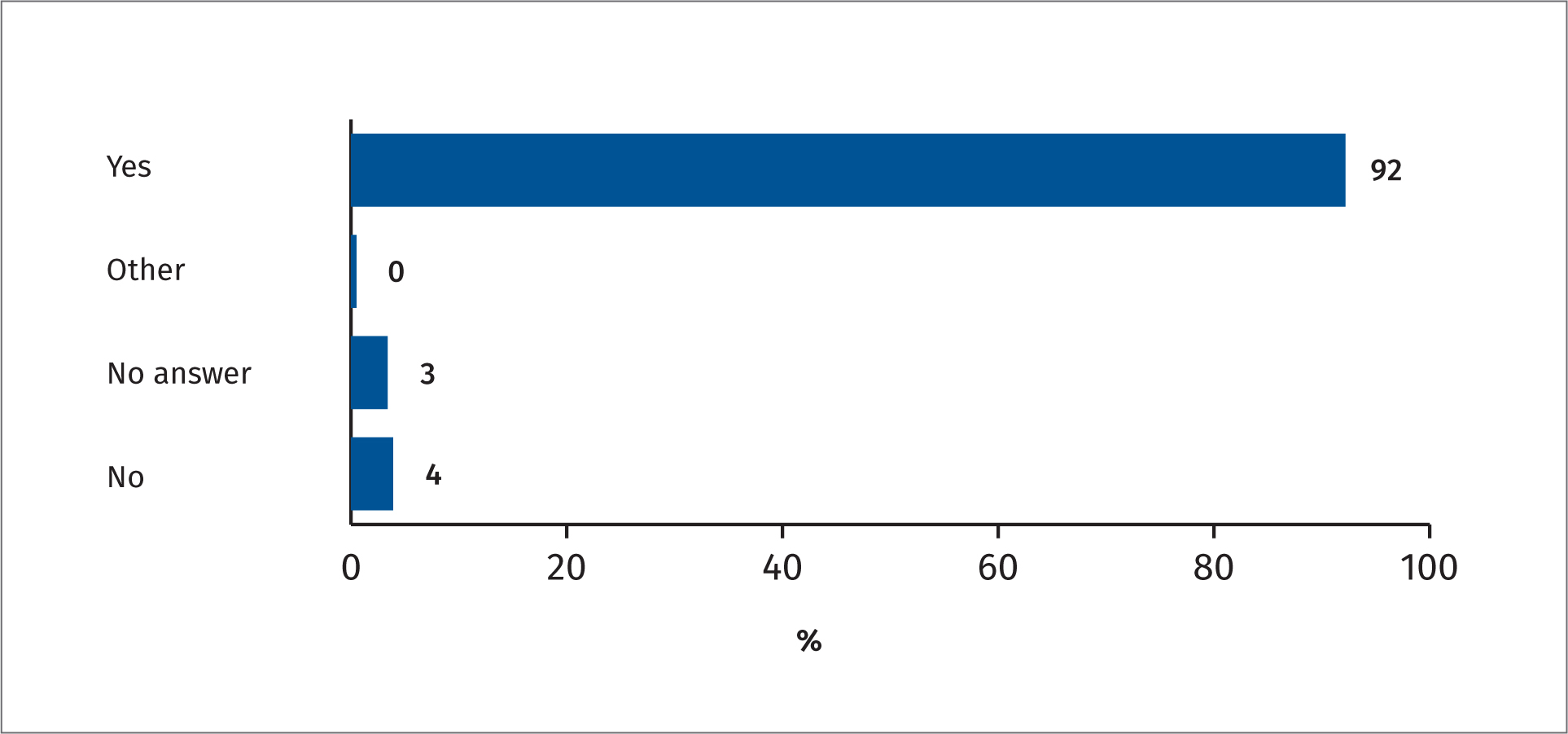

Figure 5. In your opinion, should this type of training be part of the curricula in school?

Figure 5. In your opinion, should this type of training be part of the curricula in school?

In one of the sessions, sign language translators supported us in communicating with our students, who were all hard of hearing, a very interesting experience for all involved in the session.

At the end of each session, a small questionnaire was delivered to trainers asking for feedback and to obtain a short demographic description of the participants in the session. Participants were also asked if, in their opinion and after this experience it would be appropriate to include this type of session as a mandatory topic to be taught in school. Questionnaires were distributed and later collected by the non-health professional members of the team. Questionnaires were completed anonymously and without the presence of the nurses to avoid any possible influence in the replies.

Consent from the school board had been pursued and granted prior to the day. Teachers had all been made aware of the event by the school liaison teacher and students were asked for their consent to participate in the teaching session. Participation in the sessions was fully voluntary and participants could withdraw at any time from the study.

Results

As expected, most participants were students (92%) with a smaller number of teachers and support staff (sign language translators).

Regarding age, understandably considering the nature of the school, the majority (93%) were between 14 and 19 years old, and the average age was 16 (Figure 2).

Although most of the participants had stated that they were already familiar with the topic, mainly by similar awareness sessions in school, a vast majority (92%) still stated that after the briefing sessions, their knowledge on the topic had improved and they were now more confident about acting if needed.

When asked on the relevance of integrating this type of training in the school plan of studies, 92% of the interviewed were in agreement.

Based on the answers to the questionnaire, one can conclude that all participants were very receptive and available to partake in this type of learning and training. During the sessions, everyone's interest was also high with the students showing great attention to the demonstration, actively engaging in the practice and asking pertinent questions.

Moreover, thanks to these sessions, even if they were short, the majority of the participants stated that their knowledge about BLS had increased and improved, and that they were feeling more confident to apply the competences acquired if needed. The results of this questionnaire confirm findings from similar studies, which found that teaching BLS to students can be easily applied in the school environment while also working as a multiplying factor of knowledge in BLS, mainly when students and teachers are motivated to share their experience with family and friends (Böttiger et al, 2016).

Limitations

Due to the number of classes and students in each class and the limited time available for the day, sessions were of short duration. Students were, however given, sufficient time to practice with manikins and ask any questions to the nurses present.

The study was limited to one event in Porto and further studies would be necessary to be able to generalise the findings.

Conclusions

Cardiac-respiratory arrests secondary to a cardiovascular event are still common and, although it is widely known and proven that the implementation of BLS manoeuvres as quickly as possible followed by the use of an AED are fundamental to increase survival chances and to improve the quality of life in case of cardiac arrest, the amount dedicated to promote training by policy makers is still a small percentage of the total budget for health expenditure.

One of the most efficient and low-cost ways to learn BLS would be the adoption of an annual training session of BLS in school. Findings such as the ones presented in the article help to show that the school community is very motivated to integrate BLS in their environment, as it is an important factor to strengthen, remember or acquire knowledge and techniques. Yearly training under the supervision of nursing and/or trained school staff will also contribute to raise confidence, which can help these trainees to act in the future if needed.

Nurses are well respected within the school community and may have a very important role in implementing training such as this within primary and secondary school environments, contributing to spread the awareness on the importance of BLS as an essential knowledge to be shared among the community. Events such as the World Restart a Heart Day are also essential to assert the importance of this topic among the general population.