The paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) is a challenging work environment with the demands of managing complex and critically unwell patients, physical demands of long shift/out-of-hours duties as well as the emotional demands of providing paediatric end of life care. There is a constant requirement for high performance (in both technical and non-technical skills) in a high-intensity atmosphere.

Recent studies have shown that PICU staff are at high risk of moral distress, burnout, stress, and fatigue, which can affect the ability to make critical decisions while under pressure (Colville et al, 2015; 2018; Looseley et al, 2019; McClelland et al, 2019; Jones et al, 2020). This has been shown to be a significant contributing factor in many critical incidents, not only in health care, but also in other large corporations such as NASA (Farquhar, 2017). In a health-care setting, the presence of burnout may lead to a reduction in patient safety (Gandi et al, 2011; Salyers et al, 2017; Garcia et al, 2019). Stress, burnout, and fatigue also have an impact on the physical and emotional wellbeing of staff members. Burnout has been demonstrated to be a predictor of poor physical health outcomes (such as type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease) and mental health outcomes (including insomnia, depression, and hospitalisation for mental disorders) (Salvagioni et al, 2017).

The current COVID-19 pandemic has had a worldwide effect on how we live and work. Working patterns have been adjusted to protect staff and patients, while restrictions have been put in place outside of work to protect our individual health and communities. Initial research suggests that due to the demands of the pandemic, health-care workers are now at an increased risk of developing stress-related disorders, depression and anxiety (Buselli et al, 2020; Cabarkapa et al, 2020; Elhadi et al, 2020; Tan et al, 2020).

It is recognised that most children suffer only a mild form of COVID-19 (Molteni et al, 2021); however, this does not mean there has been no impact on the PICU working environment. As of July 2021, PICANet (2021) reports 300 care episodes for 291 children who had tested positive for COVID-19; 7 children died in PICU. A small number of children with COVID-19 are now known to go on to develop a paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally linked to COVID-19 (PIMS-TS), with a proportion of these requiring admission to intensive care (Davies et al, 2020). This has necessitated a rapid formulation of management strategies for this novel and potentially serious condition.

Redeployment of staff to adult ICU has also posed challenges. Clinicians have been asked to work in unfamiliar areas, at times with little or no induction, with a patient population markedly different to the one they are used to. They have needed to become accustomed to mortality rates that far exceed those they would usually see in PICU. Staff have had to cope with these stressors while surrounded by new team members, deprived of many of their usual work support networks, and might not have had the same opportunities to debrief. For those ‘left behind’, other pressures have emerged – challenges of missing staff members, but also having to deal with feelings of guilt around not being redeployed to adults and sharing the burden. Some PICUs have been repurposed as adult ICUs – the same team may remain, but again they are faced with unfamiliar patient demands and may have to acclimatise to shifts in job roles.

We set out to explore how clinical staff in our Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) perceive their own wellbeing to be affected in this time by the changes implemented due to COVID-19.

Aim

To explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the wellbeing of clinicians working in PICU at the Royal Hospital for Children, Glasgow, with a focus on burnout, stress, work-related fatigue and work-life balance.

Methods

A single-centre, anonymised online survey was conducted. The survey was created by the authors by compiling established and validated scoring tools. A generic email invitation with a link to the survey (Appendix A) was sent to a full cohort of 30 clinicians including consultants, advanced nurse practitioners (ANPs) and trainee doctors. The survey was active online from 25/05/2020 to 28/06/2020, with a reminder email sent out halfway through this period. Baseline demographic data pertaining to staff grade (consultant, ANP, or trainee) and work pattern (full time or less than full time) was collected. The survey was divided into four sections: burnout, work-related stress, work-related fatigue, and the perceived impact on work-life balance (Appendix B).

Burnout is defined by the ICD-11 as ‘a syndrome conceptualised as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed’ and is characterised by feelings of exhaustion, mental distance from work and/or cynicism, and reduced efficacy (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2019). In this study, an abbreviated Maslach Burnout Index (aMBI) was used for assessment. 12-item tools have previously been validated (Gabbe et al, 2002; Lim et al, 2019); we utilised a 9-item survey, which has been shown to yield subscale results congruent with those obtained with the original 22-item MBI (Riley et al, 2018). It consists of 3 domains: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalisation (DP) and personal achievement (PA). Scores from 0 to 6 are given for each response, with a maximum score of 18 in each domain. The creators of the MBI, in their most up-to-date guidance, have not included strict cut-offs for the ‘diagnosis’ of burnout, recognising it as a spectrum (Mind Garden, 2019). A consensus has not been reached on criteria for burnout: some studies require high scores in EE and DP, and a low score in PA to qualify as high risk; others require high scores in both EE and DP only; some studies require a high score in only one of DP or EE (Doulougeri et al, 2016). In this study, to enable comparison with a recent survey exploring the psychological impact of working in PICU in the UK, high risk of burnout was defined as scoring ≥ 9/18 in the EE subscale, OR ≥6/18 in the DP subscale (Jones et al, 2020).

Work-related stress is defined by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) as ‘a harmful reaction people have to undue pressures and demands placed on them at work’, and is linked to high levels of absence, staff turnover, and increased error rates (Health and Safety Executive, 2020). It has also been linked to adverse health outcomes (Salvagioni et al, 2017). The Effort-Reward Imbalance (ERI) is a validated model devised by Siegrist et al, which proposes that a failure of reciprocity in the workplace (i.e. that high amounts of effort lead to minimal gains) results in strain and therefore more stress-related disorders (Siegrist et al, 1986; Siegrist, 1996; Van Vegchel et al, 2005). Further studies have demonstrated a bidirectional relationship between a high effort reward imbalance (ERI) and health outcomes: not only will this imbalance cause increased adverse outcomes, but that these adverse outcomes will then lead to increased stress (Shimazu and de Jonge, 2009). The short version of the ERI questionnaire contains 16 questions compared to the long version, which comprises 22 questions; the authors suggest that the short version is easier to utilise in large-scale investigations (Siegrist et al, 2019). Within the short form, 6 of these 16 relate to ‘over-commitment’; because these questions are not included in the effort reward ratio (ERR), they were not included in our survey. We therefore had a set of 10 questions, 3 relating to effort, and 7 relating to reward. The use of abbreviated effort-reward imbalance questionnaires has been validated (Siegrist et al, 2014). Answers are scored on a 4-point Likert scale. The ERR is calculated by dividing the effort score by the reward score, then correcting for the imbalance in number of questions for each domain:

- ERR = E/(R*c) where c = is correction factor, 3/7 (3 is the number of ‘effort’ questions, 7 is the number of ‘reward’ questions)

- An ERR of 1 suggests that for each ‘unit’ of effort, one ‘unit’ of reward is obtained i.e. efforts and rewards are balanced. An ERR >1 suggests that for a unit of reward, relatively more effort is required, whereas an ERR <1 suggests that for a unit of reward, relatively less effort is required.

Fatigue, in contrast to stress, is defined by the HSE as ‘a decline in mental and/or physical performance that results from prolonged exertion, sleep loss and/or disruption of the internal clock’ (Health and Safety Executive, no date). Fatigue can hinder decision-making, impair reaction times, and lead to higher error rates in the workplace (Greig and Snow, 2017). Respondents were first asked if they had ever experienced work-related fatigue, and then asked to what degree a set of seven factors had impacted on their levels of fatigue. These factors were based on a survey used to assess out-of-hours working and fatigue in consultants working in anaesthesia and paediatric intensive care (McClelland et al, 2019).

Work-life balance is a broad concept. A literature review published by the Department for Business Innovation and Skills considered it to encompass a number of policies including job-shares, flexible working hours, working from home, childcare support, and parental leave/pay (Smeaton et al, 2014). Our questions in this domain were based on the ones used and described in a previous study (McClelland et al, 2019). The questions had been derived from an iterative process (Delphi) by all the key stakeholders and we used the ones specifically looking at work-life balance in our staff survey. Two free text questions were included to allow staff to note their opinions and perceptions of how a new way of working affected their work-life balance. We also used this opportunity to explore staff thoughts and ideas regarding potential solutions or improvement strategies focussing on staff wellbeing. Responses were evaluated separately by three of the authors to identify the key concepts and themes which were coming through in the responses. It was hoped that these free text answers would allow the local Wellbeing Support Team (WeST) to explore future wellbeing initiatives and strategies focused specifically on the issues and suggestions made by the local clinician team.

An email invitation (Appendix A) was sent to all participants to ensure they were fully informed of the rationale for the survey. The survey was voluntary and consent was implied by the completion of the questions. The survey was anonymous. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of organisational changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic in order to help instruct future wellbeing strategy. This was considered service evaluation and therefore exempt from the requirement for ethical approval (as per The University College of London Research Ethics Committee).

Results

The survey was sent to 30 staff members. 18 responded, giving a return rate of 60%. This comprised of 2 ANPs, 9 consultants, and 7 trainees. One consultant was less than full time, the remainder full time. ANPs and trainees work on the same rota with similar duties and were considered together, enabling comparison between senior (consultants) and junior tiers (ANPs and trainees).

Descriptive analysis

Burnout

All those who responded to the online questionnaire fully completed the aMBI portion (see Table 1 for responses and Figures 1a–1c for overall scores by person). 10/18 (55.6%) respondents reported at least one high score for burnout (aMBI-EE ≥9, or aMBI-DP ≥6). All these 10 respondents had high emotional exhaustion scores with a proportion (n=4) also having high scores in depersonalisation. No respondent had an isolated high aMBI-DP without a corresponding high aMBI-EE. 100% of respondents scored ≥9 in the aMBI-PA subscale, where a higher score indicates a lower risk of burnout.

Table 1. Responses to the aMBI questions by tier (overall/senior/junior)

| Every day | A few times a week | Once a week | A few times a month | Once a month or less | A few times a year | Never | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I deal very effectively with the problems of my patients (aMBI-PA) | Overall (n=18) | 11 (61.1%) | 5 (27.8%) | 1 (5.6%) | 1 (5.6%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Seniors (n=9) | 6 (66.7%) | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 5 (55.6%) | 3 (33.3%) | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2. I feel I treat some patients as if they were impersonal objects (aMBI-DP) | Overall (n=18) | 0 | 1 (5.6%) | 2 (11.1%) | 1 (5.6%) | 3 (16.7%) | 3 (16.7%) | 8 (44.4%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (22.2%) | 4 (44.4%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (11.3%) | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (11.1%) | 4 (44.4%) | |

| 3. I feel emotionally drained from my work (aMBI-EE) | Overall (n=18) | 1 (5.6%) | 2 (11.1%) | 4 (22.2%) | 5 (27.8%) | 3 (16.7%) | 3 (16.7%) | 0 |

| Seniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0 | 3 (33.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0 | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 0 | 0 | 4 (44.4%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | |

| 4. I feel fatigued when I get up in the morning and have to face another day on the job (aMBI-EE) | Overall (n=18) | 1 (5.6%) | 3 (16.7%) | 2 (11.1%) | 3 (16.7%) | 5 (27.8%) | 3 (16.7%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 0 | 2 (22.2%) | 0 | 2 (22.2%) | 3 (33.3%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0 | |

| 5. I have become more calloused towards people since I took this job (aMBI-DP) | Overall (n=18) | 1 (5.6%) | 0 | 1 (5.6%) | 3 (16.7%) | 1 (5.6%) | 4 (22.2%) | 8 (44.4%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 2 (22.2%) | 4 (44.4%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (22.2%) | 4 (44.4%) | |

| 6. I feel I've positively influenced other people's lives through my work (aMBI-PA) | Overall (n=18) | 5 (27.8%) | 5 (27.8%) | 4 (22.2%) | 2 (11.1%) | 1 (5.6%) | 1 (5.6%) | 0 |

| Seniors (n=9) | 4 (44.4%) | 3 (33.3%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | |

| 7. Working with people all day is really a strain for me (aMBI-EE) | Overall (n=18) | 0 | 2 (11.1%) | 3 (16.7%) | 3 (16.7%) | 1 (5.6%) | 5 (27.8%) | 4 (22.2%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 0 | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | 3 (33.3%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 3 (33.3%) | 0 | 4 (44.4%) | 1 (11.1%) | |

| 8. I don't really care what happens to some people (aMBI-DP) | Overall (n=18) | 0 | 1 (5.6%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (11.1%) | 3 (16.7%) | 12 (66.7%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | 6 (66.7%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (22.2%) | 6 (66.7%) | |

| 9. I feel exhilarated after working closely with my patients (aMBI-PA) | Overall (n=18) | 6 (33.3%) | 4 (22.2%) | 3 (16.7%) | 3 (16.7%) | 1 (5.6%) | 1 (5.6%) | 0 |

| Seniors (n=9) | 3 (33.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | 3 (33.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 3 (33.3%) | 3 (33.3%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 0 |

Work-related stress

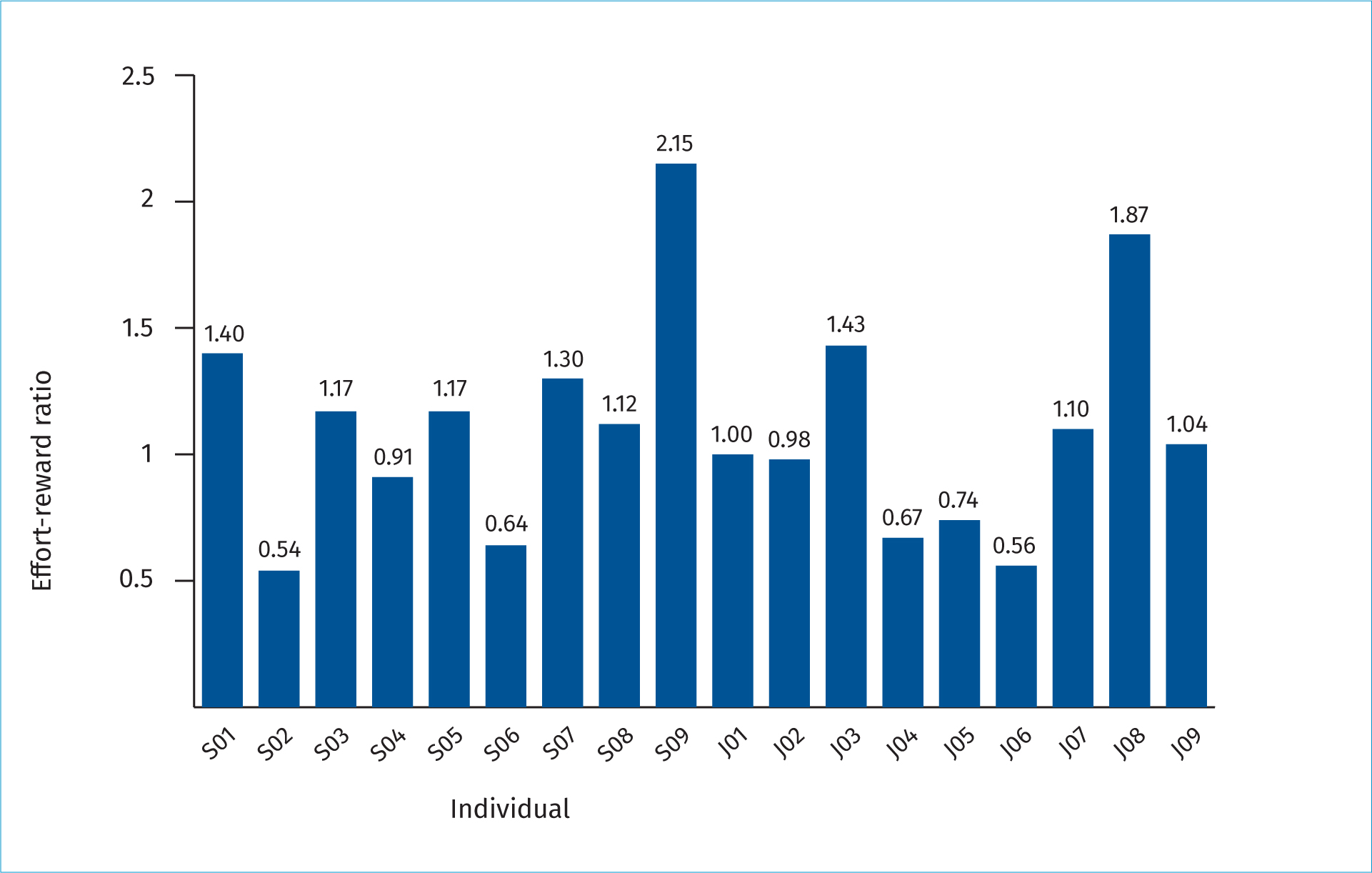

All those who responded to the survey fully completed the ERI set of questions (see Tables 2 and 3). ERR scores greater than 1 were returned by 10 respondents (55.6%), implying reduced gains compared to effort (see Figure 2). Mean ERR was 1.10 for the whole group.

Table 2. Responses to the ERI Questionnaire (Effort Scale) by tier (overall/senior/junior)

| Question | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERI1 - I have constant time pressure due to a heavy workload. | Overall (n=18) | 2 (11.1%) | 6 (33.3%) | 5 (27.8%) | 5 (27.8%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 0 | 3 (33.3%) | 3 (33.3%) | 3 (33.3%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 5 (55.6%) | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (22.2%) | |

| ERI2 – I have many interruptions and disturbances while performing my job. | Overall (n=18) | 0 | 7 (38.9%) | 5 (27.8%) | 6 (33.3%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 0 | 3 (33.3%) | 3 (33.3%) | 3 (33.3%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 0 | 4 (44.4%) | 2 (22.2%) | 3 (33.3%) | |

| ERI3 – Over the past few years, my job has become more and more demanding. | Overall (n=18) | 0 | 4 (22.2%) | 7 (38.9%) | 7 (38.9%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 4 (44.4%) | 4 (44.4%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 0 | 3 (33.3%) | 3 (33.3%) | 3 (33.3%) |

Table 3. Responses to the ERI Questionnaire (Reward Scale) by tier (overall/senior/junior)

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERI4 – I receive the respect I deserve from my superior or a respective relevant person. | Overall (n=18) | 1 (5.6%) | 4 (22.2%) | 12 (66.7%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 3 (33.3%) | 5 (55.5%) | 0 | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 7 (77.8%) | 1 (11.1%) | |

| ERI5 – My job promotion prospects are poor. | Overall (n=18) | 2 (11.1%) | 9 (50.0%) | 4 (22.2%) | 3 (16.7%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 5 (55.6%) | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (11.1%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 4 (44.4%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (22.2%) | |

| ERI6 – I have experienced or I expect to experience an undesirable change in my work situation. | Overall (n=18) | 3 (16.7%) | 9 (50.0%) | 4 (22.2%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 2 (22.2%) | 4 (44.4%) | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (11.1%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 5 (55.6%) | 3 (33.3%) | 0 | |

| ERI7 – My job security is poor. (n=18) | Overall | 9 (50.0%) | 4 (22.2%) | 3 (16.7%) | 2 (11.1%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 7 (77.8%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 2 (22.2%) | 3 (33.3%) | 3 (33.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | |

| ERI8 – Considering all my efforts and achievements, I receive the respect and prestige I deserve at work. | Overall (n=18) | 1 (5.6%) | 5 (27.8%) | 10 (55.6%) | 2 (11.1%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 3 (33.3%) | 4 (44.4%) | 1 (11.1%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 0 | 2 (22.2%) | 6 (66.7%) | 1 (11.1%) | |

| ERI9 – Considering all my efforts and achievements, my job promotion prospects are adequate. | Overall (n=18) | 2 (11.1%) | 4 (22.2%) | 8 (44.4%) | 4 (22.2%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | 5 (55.6%) | 2 (22.2%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 3 (33.3%) | 3 (33.3%) | 2 (22.2%) | |

| ERI10 – Considering all my efforts and achievements, my salary/income is adequate. | Overall (n=18) | 0 | 2 (11.1%) | 11 (61.1%) | 5 (27.8%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 0 | 0 | 6 (66.7%) | 3 (33.3%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 0 | 2 (22.2%) | 5 (55.6%) | 2 (22.2%) |

Overlap between burnout and work-related stress was noted, as 7 respondents had both an ERR>1, and high aMBI scores in at least one of aMBI-EE or aMBI-DP.

Fatigue and work-life balance

Staff members were first asked whether they had experienced work-related fatigue – 17 answered this question, with 82.4% responding that they had (see Table 4). The difficulty to take breaks was the most commonly cited contributing factor to fatigue (77.8% reporting a significant or moderate impact). ‘Challenges of remote communication’ (including breaking bad news) was the factor that was least frequently reported to have a significant or moderate impact (35.3% overall) (see Table 5).

Table 4. Responses to the question, ‘Have you experienced work-related fatigue?’ by tier (overall/senior/junior)

| Yes | No | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=17) | 14 (82.4%) | 3 (17.6%) |

| Seniors (n=8) | 8 (100%) | 0 |

| Juniors (n=9) | 6 (66.7%) | 3 (33.3%) |

Table 5. Responses to the question, ’Other than your working pattern, which of the following factors do you believe contribute to your fatigue/exhaustion levels?’ by tier (overall/senior/junior)

| Significant | Moderate | Minimum | Nil | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 – Ability to take breaks during clinical work | Overall (n=18) | 5 (27.8%) | 9 (50.0%) | 1 (5.6%) | 3 (16.7%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 6 (66.7%) | 0 | 2 (22.2%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 4 (44.4%) | 3 (33.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | |

| Q2 – Staffing issues-colleague sickness/isolation and understaffing | Overall (n=18) | 7 (38.9%) | 5 (27.8%) | 4 (22.2%) | 2 (11.1%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 6 (66.7%) | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0 | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 4 (44.4%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (22.2%) | |

| Q3 – Staffing issues-rota gaps and last minute changes to cover | Overall (n=18) | 4 (22.2%) | 8 (44.4%) | 4 (22.2%) | 2 (11.1%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 3 (33.3%) | 4 (44.4%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0 | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 4 (44.4%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (22.2%) | |

| Q4 – Non-clinical workload | Overall (n=18) | 5 (27.8%) | 8 (44.4%) | 4 (22.2%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 4 (44.4%) | 4 (44.4%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 4 (44.4%) | 3 (33.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | |

| Q5 – Stress of (potential or actual) complaints, disciplinary action or litigation | Overall (n=18) | 2 (11.1%) | 8 (44.4%) | 6 (33.3%) | 2 (11.1%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 2 (22.2%) | 4 (44.4%) | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (11.1%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 0 | 4 (44.4%) | 4 (44.4%) | 1 (11.1%) | |

| Q6 – Expectations from patients and families | Overall (n=18) | 2 (11.11%) | 9 (50.0%) | 6 (33.3%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 2 (22.2%) | 4 (44.4%) | 3 (33.3%) | 0 | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 0 | 5 (55.6%) | 3 (33.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | |

| Q7 – Remote communication with relatives e.g breaking bad news over the phone | Overall (n=17)* | 2 (11.8%) | 4 (23.5%) | 7 (41.2%) | 4 (23.5%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (22.2%) | 5 (55.6%) | 1 (11.1%) | |

| Juniors (n=8)* | 1 (12.5%) | 2 (25.0%) | 2 (25.0%) | 3 (37.5%) |

The majority (55.5%) disagreed or strongly disagreed that work-life balance had improved due to the COVID-19 pandemic. All 3 factors explored (remote working, messaging groups, and media coverage) were generally felt to have had a negative impact on work-life balance (see Table 6).

Table 6. Perceptions of staff of the impact of COVID-19 on work-life balance by tier (overall/senior/junior)

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 – My work-life balance has improved now compared to prior to the COVID19 pandemic. | Overall (n=18) | 1 (5.6%) | 2 (11.1%) | 5 (27.8%) | 6 (33.3%) | 4 (22.2%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 0 | 0 | 3 (33.3%) | 4 (44.4%) | 2 (22.2%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (22.2%) | |

| Q2 – Remote working and working from home has improved my work-life balance | Overall (n=18) | 1 (5.6%) | 5 (27.8%) | 2 (11.1%) | 7 (38.9%) | 3 (16.7%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 0 | 2 (22.2%) | 0 | 5 (55.6%) | 2 (22.2%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 3 (33.3%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (11.1%) | |

| Q3 – Closed messaging groups and social media has improved my work-life balance | Overall (n=18) | 0 | 1 (5.6%) | 3 (16.7%) | 9 (50.0%) | 5 (27.8%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (55.6%) | 4 (44.4%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 3 (33.3%) | 4 (44.4%) | 1 (11.1%) | |

| Q4 – Media coverage and public reaction has improved my work-life balance | Overall (n=18) | 1 (5.6%) | 0 | 6 (33.3%) | 4 (22.2%) | 7 (38.9%) |

| Seniors (n=9) | 0 | 0 | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (22.2%) | 5 (55.6%) | |

| Juniors (n=9) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 4 (44.4%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (22.2%) |

Comparison between senior tier and junior tier

Burnout mean scores for the group overall were 14.33 for aMBI-PA, 3.44 for aMBI-DP, and 8.06 for aMBI-EE. Senior tier clinicians, when compared to juniors, had a higher mean score for depersonalisation (4.00 vs 2.89) and emotional exhaustion (8.56 vs 7.56). They also had a higher mean score for personal achievement (15.00 vs 13.67). The criteria for having a high burnout score was met in an equal number of senior and junior tier clinicians (n=5 in each group); as previously noted, all of these had high emotional exhaustion scores. Of those who also had high depersonalisation scores (n=4), 3 were senior tier.

Work-related stress

The mean ERR was 1.10. Seniors had a slightly higher ERR than juniors (1.15 compared to 1.04).

Fatigue and work-life balance

100% of seniors reported experiencing work-related fatigue compared to 66.67% of juniors. Seniors were also generally more likely to report a negative impact on work-life balance. In comparison, 33.33% of juniors felt that work-life balance had improved after the onset of the pandemic, compared to none of the seniors. 77.78% of seniors felt remote working had negatively impacted on balance compared to 33.3% of juniors. Similarly, 100% of seniors felt that messaging groups and social media had had a negative impact compared to 55.56% of juniors. 77.78% of seniors felt media coverage and public reaction was detrimental to their work-life balance, compared to 44.44% of juniors.

Analysis of free text responses

Question: Please comment on how your work-life balance has changed during the COVID-19 pandemic

Twelve members of staff responded to this question: 7 consultants, 4 trainees, and 1 ANP. The common domains and themes identified on independent review of three authors (AC, EB, PD) are illustrated, in Table 9, alongside illustrative examples. In titling the domains, we have identified parallels with the Safety Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model, which is based on a human factors framework and has gone through a number of iterations (Carayon et al, 2020).

Table 7. aMBI Subscales by tier (overall/senior/junior)

| aMBI-PA | aMBI-DP | aMBI-EE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (mean, range) | 14.33 (10–18) | 3.44 (0–16) | 8.06 (1–17) |

| Seniors (mean, range) | 15.00 (11–18) | 4.00 (0–16) | 8.56 (1–17) |

| Juniors (mean, range) | 13.67 (10–17) | 2.89 (0–6) | 7.56 (4–10) |

Table 8. ERR by tier (overall/senior/junior)

| Effort | Reward | Esteem | Promotion | Security | ERR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (mean, range) | 8.83 (6–12) | 19.83 (13–27) | 5.44 (2–12) | 8.50 (5–12) | 5.89 (3–8) | 1.10 (0.54-2.14) |

| Seniors (mean, range) | 9.33 (6–12) | 20.22 (13–26) | 5.00 (2–7) | 8.89 (5–12) | 6.33 (4–8) | 1.15 (0.54-2.15) |

| Juniors (mean, range) | 8.33 (6–12) | 19.44 (14–27) | 5.89 (4–8) | 8.11 (5–12) | 5.44 (3–8) | 1.04 (0.56-1.87) |

Table 9. ‘Please comment on how your work-life balance has changed during the COVID-19 pandemic’

| Domain (number of participants highlighting topic) with breakdown of themes | Example quote |

|---|---|

| Work content and demands/’tasks’, ‘organisation’ (8) | |

|

‘I also have an increased work load so increased demands due to covid prevent having days off. Very few days are free of work related activity.’ S01‘Multi-tasking – engaging with and flitting between many different meeting agendas – all with expectations. Bombarded with the opportunity to attend many, continually, daily. Multiple training opportunities – how do you choose which to accept?’ S07 |

| Home and personal demands/’environment’, ‘person’ (6) | |

|

‘Improved in some respects with more time at home but worse in others: challenging to complete increase in non-clinical work from home with no childcare available. This has increased pressure both professionally and personally.’ S06 ‘Work has crept into every room at home, every hour and everyday’. J08 |

| Isolation and engagement/’organisation’, ‘environment’ (5) | |

|

‘I have felt the PICU COVID response left us out of the loop and training opportunities significantly reduced. That causes stress in itself and feeling deskilled and not valued with regard to strategic response and not actively engaged by senior clinicians.’ J03‘difficulty not feeling as part of a team as despite this intrusion you see people less often or in strange circumstances eg zoom’. S03 |

| Intrusion and blurred boundaries/’technology’, ‘organisation’ (8) | |

|

‘Intrusive whatsapp and teams messages means can never switch off’. S05‘I have stopped reading or listening to the news daily, as it was starting to depress me while heightening my fears of going to work.’ S09 |

Question: Please comment on any potential solutions or preventative measures that you feel could improve your wellbeing.

Thirteen staff members gave answers to the question above (8 consultants, 3 trainees, 2 ANPs). We have again listed the common domains and key themes identified in Table 10, with illustrative examples given.

Table 10. ‘Please comment on any potential solutions or preventative measures that you feel could improve your wellbeing.’

| Domain (number of participants highlighting topic) with breakdown of themes | Example quote |

|---|---|

| Social media/‘technology’(6) | |

|

‘Strict rules around whatsapp use’. S05‘Curfews on work-related social media posts.’ S07 |

| Work-life balance/‘organisation’ (8) | |

|

‘We need to be clear with ourselves and allocate rest days. We also need to be transparent about how much non-clinical work is expected of us i.e. how many hours a week should we do and how do we stop once this limit has been reached.’ S01‘Ability to come into the office for non-clinical work. i.e. balance of some remote non-clinical work but appreciation that the ability to come in for certain pieces of work is important for productivity: especially when there has been an increase in expectation to contribute to non-clinical COVID work.’ S06 |

| Expectations and interpersonal relationships/‘people’ (3) | |

|

‘Friendship and camaraderie with colleagues is a great help, as is having the resources to do the best for one's patients’. S04‘I strongly believe that wellbeing is also very closely related to how people are treated at work, and for this reason, I believe that if everyone is valued, and treated fairly by those around him, then certain negative impacts of work can be overcome by this caring behaviour. Treat others, as you want them to treat you. It's the basic law of humanity on which wellbeing balances.’ S09 |

| Wellbeing service and training opportunities/‘environment’ (3) | |

|

‘Have areas which are wellbeing free or just blank-or one room with nothing on the wall. Have a more personalised wellbeing service – as individuals.’ J08‘More patient procedures’. J06 |

Discussion

There is no consensus on the criteria for burnout. Our study suggests that, with the additional impact of the COVID-19 global pandemic, the staff on our unit are at a higher risk of burnout than rates identified in previously published studies (Gandi et al, 2011; Colville et al, 2018; Jones et al, 2020). It is reasonable to assume that our PICU is representative of units across the UK; the number of units within the UK is small, and they have all been similarly exposed to the challenges posed by the global pandemic. This would suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the risk of burnout across the nation.

Emotional exhaustion is a recognised issue in the intensive care environment (Colville et al, 2018; Jones et al, 2020). High emotional exhaustion scores in both the junior and senior tiers suggest that this is a global issue rather than one focused on medical hierarchy. High scores in the depersonalisation subscale were less frequently seen, in keeping with previous studies (Gandi et al, 2011; Jones et al, 2020); however, again it is worth noting that compared to Jones et al's 2020 study we have identified higher emotional exhaustion scores and depersonalisation scores in the setting of the global pandemic (55.6% vs 48%, 22% vs 10%).

Interestingly, staff scored highly for their sense of personal achievement, suggesting that people do feel that their work is worthwhile. This is perhaps even more profound than before the pandemic, as previous studies report a lack of personal achievement in up to 46% of surveyed staff. Personal achievement does, however, come at a cost which is highlighted by the perceived negative imbalance between works and gains (ERR>1). Levels of work-related stress have increased throughout the NHS; 44% of staff who responded to the NHS 2020 annual survey reported feeling unwell due to work-related stress, compared to 40% in 2019 (NHS Employers, 2021). It is not difficult to understand that working during a global pandemic is exhausting and staff reporting having to work harder to maintain a high standard of care is well described (Buselli et al, 2020; Elhadi et al, 2020; Mohd Fauzi et al, 2020; Tan et al, 2020). While not directly comparable, the fact that 55.6% of our staff had an ERR>1 suggests that PICU staff may be more at risk of work-related stress than NHS employees in general.

Almost all respondents had experienced work-related fatigue, consistent with McClelland et al's 2019 study, where over 90% of consultants working in anaesthesia and intensive care reported experiencing fatigue. It is interesting to note that it was only within the junior tier that this was not reported, while every consultant who responded reported fatigue. Higher scores in the consultant group compared to juniors is perhaps reflective of the additional responsibilities for rotas and ensuring adequate staffing that senior medics have compared to more junior colleagues. Similarly, consultants were those most likely to feel that complaints or threats of litigation impacted more heavily on fatigue, perhaps again due to their seniority and higher levels of responsibility. Unsurprisingly, the necessity of taking breaks was highlighted at all levels. The majority of staff felt that staffing challenges has a large impact on levels of work-related fatigue.

The area reported to have the smallest impact on fatigue was in the challenges of communicating remotely with relatives. There are a number of potential explanations for this. It might be that PICU staff in general are used to difficult conversations and therefore it is not too much of a stretch to add additional challenges such as virtual communication. It might also be that people are better at recognising physical causes of fatigue (no breaks, short staffing) or immediately obvious threats (e.g. complaints) than more insidious emotional stressors.

Work-life balance is not felt to have improved during the COVID-19 pandemic. While working from home increases flexibility and the ability to limit the number of staff members in clinical areas, it is perceived to have a deleterious impact on balance, especially amongst the consultant body. This may indicate that consultants have a greater burden of non-clinical responsibilities and therefore might end up taking more of this home. Similarly, utilisation of social media platforms increases accessibility while negatively impacting on work life balance. Again, consultants seemed to be those with the most negative perception of this. This is reflected by the number of consultants who mentioned social media intrusiveness and the possible benefits of curfews in their free text answers. This may suggest that out of hours, it is more likely for an off-duty consultant to be contacted for advice by a junior than it is for a trainee to be contacted by another staff member, or even for consultants to contact each other than it is more inter-junior queries. Media coverage is again noted to have a negative effect; this was noted most by consultants. Junior staff are perhaps better able to filter their social media news feeds, or this could reflect the need for senior clinicians to be more up to date regarding the impact of fast-paced government-led changes on policy to enable effective governance and management decisions.

Limitations

A variety of tools exist to assess burnout, stress, and fatigue; even when the same questionnaires are utilised, there is disagreement surrounding ‘cut-offs’ for the assessment of risk (Doulougeri et al, 2016). This can make it difficult to draw comparisons between studies. In an attempt to maintain anonymity for the small cohort, the opening questions regarding demographics were kept to a minimum, only asking for the participants to indicate if they were consultants or trainees/ANPs and if they work full-time or less than full time (LTFT). Arguably, this limits the identification of particular groups susceptible to psychological stress and fatigue, which may be an area to explore in more detail in the future to allow for more targeted solutions. Comparison between staff grades is difficult due to small sample sizes, particularly in the ANP group with only two members; however, where possible, trends and patterns have been noted and would warrant further exploration in larger samples. This study could also be expanded in the future to other centres and to other staff groups but that was out of the remit of this study. Nursing staff are critical team players and it would be useful to assess their wellbeing, along with perceived barriers or challenges. This could facilitate an approach to wellbeing that encompasses a greater section of the PICU.

Conclusions

Staff members working on PICU are at risk of burnout, work-related stress, and fatigue, regardless of seniority. Multiple factors specific to the COVID-19 pandemic have been identified as possible exacerbating factors, such as a negative shift in work-life balance with a blurring of boundaries and intrusion of work life into the home (and vice versa), an increased sense of isolation and lack of engagement, and a lack of ‘COVID-19-free’ time. Strategies to combat this should take a holistic approach in considering both the person and their environment.

So how can we improve wellbeing?

We have highlighted how potential strategies to improve wellbeing might correlate with the SEIPS model. While this is widely used in health-care settings as a model to prevent error and patient harm, we might also consider whether it can be applied to prevent clinician harm. We need to think about how we can modify the environment, the use of technology, the interactions between people, and the way that the unit and tasks are organised. Initial possibilities include:

- Approaches to burnout might be prudent to note the domain scores – support is needed for emotional exhaustion (perhaps to a greater degree than depersonalisation) – and should play on the strengths (i.e. that staff get a lot of personal achievement from the job). For example, utilising Learning from Excellence or GREATix to highlight good practice could reiterate personal achievements. Balint groups is one strategy that has recently been demonstrated to reduce emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation and could be delivered virtually (Stojanovic-Tasic et al, 2018; Huang et al, 2020; Pattni et al, 2020).

- Social media agreements should be in place – for example it is a reasonable expectation that if not on call, messaging groups will be muted and staff members will not routinely respond to these. An important step is making sure all staff members have the knowledge of how to actually mute notifications – assumptions should not be made.

- Boundaries when working from home should be established and this is fundamental for wellbeing. These boundaries need to be considered both by individuals (self-care) and by systems (having a safe contact policy stipulating the importance of protected time.

- It has been highlighted by free-text responses that the wellbeing drives have been quite senior led; it is important to collaborate with junior staff and to give them a voice. The importance of having senior buy-in for fundamental change cannot be understated but all wellbeing initiatives should be as collaborative and inclusive as possible.

KEY POINTS

- This study builds on previous studies of PICU staff wellbeing by exploring the additional impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- High levels of burnout, work-related stress and fatigue were identified, as well as a negative perception of the impact of the pandemic on work-life balance.

- Strategies to improve staff wellbeing must be sought from those most affected.

- The findings from this study should be shared with other centres experiencing similar circumstances.

REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- Have you considered your own risk of any of the work-related disorders we discuss here? Has your workplace carried out any surveys to assess employee risk?

- What strategies has your workplace employed to improve wellbeing, and were these informed by staff feedback?

- What other methods of improving wellbeing could be implemented in your workplace?