Two of the biggest health concerns regarding child health, worldwide, are dental caries and obesity (Carson et al, 2017). In the most recent UK Child Dental Health Survey, obvious tooth decay was apparent in the primary teeth of 46% of 8-year-olds, and in the permanent teeth of 46% of 15-year-olds (NHS, 2013). Over one-third of 12-year-olds reported that they were embarrassed to smile and laugh because of their teeth, and over half felt their day-to-day activities had been affected by tooth-related problems. Similarly, obesity has a considerable impact on quality of life and is associated with a wide range of medical conditions including type II diabetes, heart disease and cancers, which can have longstanding effects into adulthood (Bhadoria et al, 2015). While the determinants of these two diseases are multifactorial, lifestyle choices, such as unhealthy food selections and frequent snacking, are known to have a significant impact on the development of both (Lake and Townshend, 2006).

Watching television remains a significant part of children's lives in the UK, with viewing times averaging 14 hours per week (Office of Communications [Ofcom], 2017). A number of explanations for the theorised link between obesity and watching television have been proposed, with increases in sedentary behaviour and/or consumption of snack foods and total calorie intake correlating to increased television viewing (Halford et al, 2004; Wiecha et al, 2006; Roberts et al, 2017). Most significantly, the World Health Organization (2010) has identified and acknowledged that television advertisements promoting nutrient-poor and energy--dense foods are a plausible determinant for children being overweight and obese.

Television advertisements provide an effective medium for food companies to target children and influence their food choices (Boyland and Halford, 2013). Multiple systematic reviews have shown that child exposure to television advertisements directly impacts food preferences, attitudes and eating habits (Cairns et al, 2013).

‘Television advertisements provide an effective medium for food companies to target children and influence their food choices…Multiple systematic reviews have shown that child exposure to television advertisements directly impacts food preferences, attitudes and eating habits…’

Healthcare professionals and consumer associations have identified the need for greater control over the types of foods promoted to children. Since 2006, two independent regulators of television advertising, Ofcom and the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) have tightened regulations related to advertising to child audiences. Notably, these included a ruling that all high in fat, salt or sugar (HFSS) products be eliminated from television programmes engaging largely child audiences (Ofcom, 2007). Scales such as ‘Nutrient Profiling’ and ‘Traffic Light Labelling’ developed by the Food Standards Agency (FSA) have been utilised by Ofcom in this practice (Department of Health, 2011).

Comparison of data before and after the introduction of new regulations suggests there has been a reduction in children's exposure to both food and drink television advertisements as a whole, and the proportion of these that contain HFSS products (ASA, 2018). However, many of these studies overlooked the fact that children access channels that are not specifically targeted to them. Interestingly, 70% of children's television viewing takes place during adult airtime (Ofcom, 2017). This is likely to impact the extent and types of television advertisements they are exposed to, which is concerning since the restrictions on HFSS television advertising are not enforced on adult channels.

Objectives

This study aimed to:

- Determine the current frequency and proportion of food and drink television advertisements children are exposed to

- Analyse the nutritional content of the food and drink products that children are exposed to via television adverts

- Determine whether the target age group of a television channel affects the frequency and nature of the food and drink products advertised.

Methods

Review of data from the Broadcasters' Audience Research Board (BARB, 2020) and television channels' stated target audiences allowed categorisation and selection of the most popular television channels by age of intended viewership as follows:

- Pre-school (<6 years old): Nickelodeon Junior and Disney Junior

- Pre-teen and teen (6–15 years old): Nickelodeon and Disney Channels

- Adult (>15 years old): BBC and ITV.

During a 5-month period (January–May 2018), each children's television channel was individually viewed for a total of 16 hours, consisting of 10 weekday and 6 weekend hours. As the BBC channels do not broadcast advertisements, these channels were excluded from the study. Instead, ITV was viewed for 20 weekday and 12 weekend hours to give each target age group the same weighting. A single observer analysed a total of 96 hours of broadcasting and a spread of channels were viewed each week.

Data collection occurred during children's typical peak viewing hours, as reported by Ofcom (2017), this was between 6pm–9pm on weekdays, and either 9am–12pm or 4pm–7pm at the weekend. Data collection only took place during school term-time to minimise ‘holiday’ influence on the television advertisements analysed. Information was gathered with the aid of a digital stopwatch, including:

- Name of television channel

- Date and day of the week

- Total number of television advertisements

- Advertisement categorisation, split into ‘food/drink’ or ‘non-food/drink’

- Total time of television watched (seconds)

- Total time dedicated to advertisements (seconds)

- Total time dedicated to advertisements in the ‘food/drink’ category

- Name, brand and nutritional value of all ‘food/drink’ products advertised.

The exclusion criteria were channels not funded by advertisements, advertisements for forthcoming television programmes, and programmes broadcast during the school holidays.

The nutritional values of food/drinks advertised, including the products' fat, salt and sugar content, were researched online and analysed by application of the FSA traffic light labelling system (Department of Health, 2016), as illustrated in Table 1, rather than the ‘Nutrient Profiling’ system, as it was readily comparable to food/drink labelling, giving a quick objective indication of the salt, sugar and fat content of the product.

Table 1. Classification for food and drink, based on the Food Standard Agencies traffic light system

| Food (g per 100g) | Drink (ml per 100ml) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugar | Total fat | Salt | Sugar | Total fat | Salt | |

| Low | ≤5 | ≤3 | ≤0.3 | ≤2.5 | ≤1.5 | ≤0.3 |

| Medium | 5–22.5 | 3–17.5 | 0.3–1.5 | 2.5–11.25 | 1.5–8.75 | 0.3–0.75 |

| High | >22.5 | >17.5 | >1.5 | >11.25 | >8.75 | >0.75 |

The primary outcome measures were the frequency and proportion of food and drink advertisements within each of the intended age-groups. The secondary outcome measure was the nutritional content, as indicated by FSA, of each food and drink advertised.

Data were interpreted and additional statistical analyses conducted to compare the categorical data using the Pearson Chi-squared test, with P<0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

During the 96 hours of television programmes analysed, a total of 2482 advertisements were broadcast, of which 235 were food and drink related. Overall, television advertisements accounted for 17.3% of the total broadcasting time, or an average of 10.4 minutes per hour.

Table 2 shows the percentage, frequency and broadcasting time of food and drink advertisements in accordance with the target audience of the television channel. A statistically significant difference was found between the frequency of food and drink advertisements and the target age group of the television channel (X2=112.5, df=2, P<0.001), with adult television channels having a much higher rate of food and drink advertisements (4.8 food/drink advertisements per hour) compared with the combined children's television channels (1.0 food/drink advertisements per hour). Furthermore, channels specifically targeted towards younger children broadcast fewer food and drink advertisements in comparison with those targeted towards older children.

Table 2. Broadcasting statistics of food/drink advertisements by target audience of channel

| Proportion of total advertisements (%) | Mean frequency (per hour) | Mean broadcasting time (seconds per hour) | Total contribution to age category (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-school | 26 (3.1) | 0.8 | 18 | 11 |

| Pre-teen and teen | 56 (6.7) | 1.8 | 41 | 24 |

| Adult | 153 (19) | 4.8 | 101.1 | 65 |

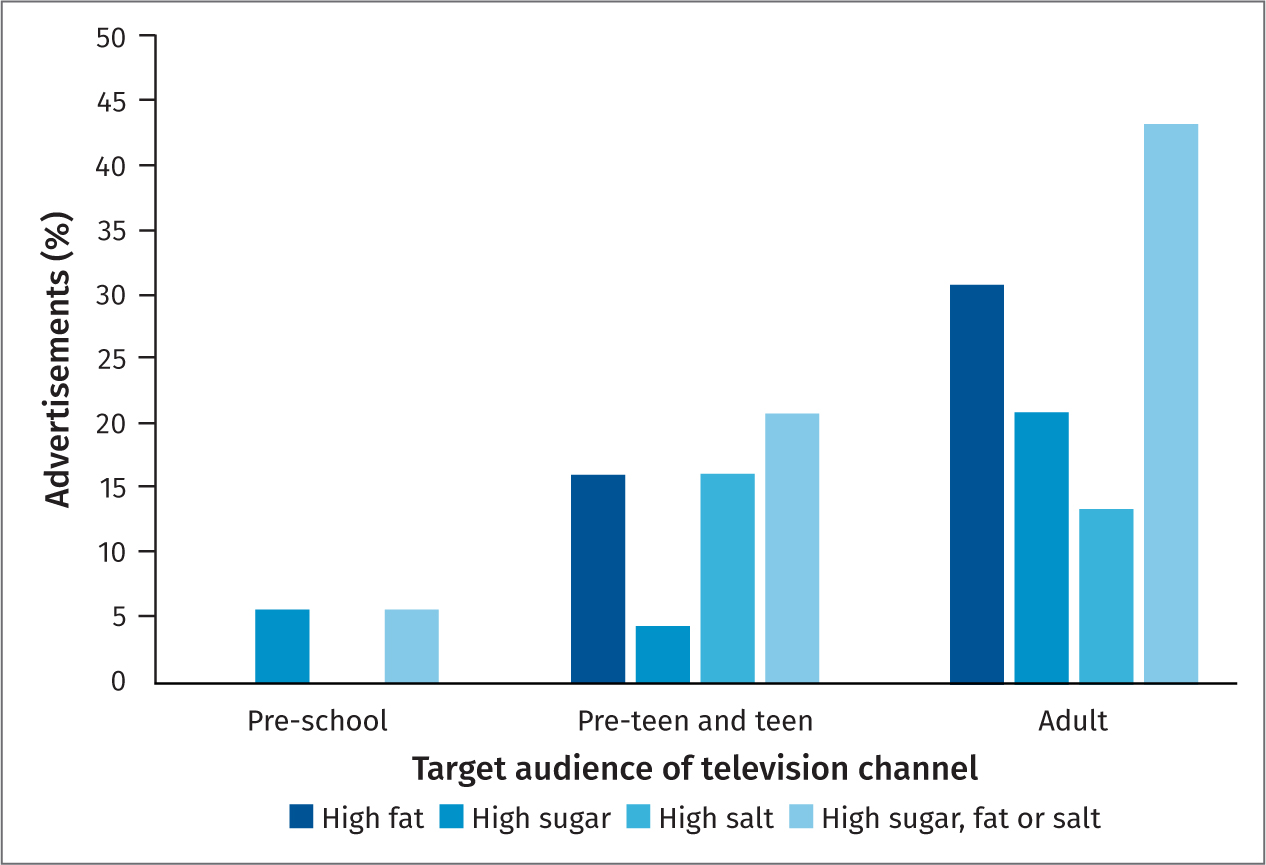

Table 3 provides an analysis of the nutritional content of the food and drink products advertised in accordance with the target audience of the television channel. Of the total 235 food and drink advertisements, 31.9% promoted HFSS products. As illustrated in Figure 1, there was a statistically significant difference between the target audience of the television channel and the frequency of HFSS products advertised (X2=16.8, df=2, P<0.001). The proportion of HFSS advertisements was significantly lower on television channels primarily targeted towards younger children when compared to television channels primarily targeted towards older children.

Table 3. Analysis of nutritional content of food and drink products advertised

| Proportion of food and drink advertisements, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-school | Pre-teen and teen | Adult | Overall (all channels) | |

| High sugar | 1 (5.9) | 2 (4.7) | 17 (21.0) | 20 (14.2) |

| High fat | 0 (0) | 7 (16.3) | 25 (30.9) | 32 (22.7) |

| High salt | 0 (0) | 7 (16.3) | 11 (13.6) | 18 (12.8) |

| High fat, sugar or salt (HFSS) | 1 (5.9) | 9 (20.9) | 35 (43.2) | 45 (31.9) |

| Low or moderate sugar | 16 (94.1) | 34 (79.1) | 56 (69.1) | 106 (75.2) |

| Low or moderate fat | 17 (100) | 34 (79.1) | 51 (63.0) | 103 (72.3) |

| Low or moderate salt | 17 (100) | 34 (79.1) | 63 (77.8) | 114 (80.9) |

| Low or moderate fat, salt and sugar (Not HFSS) | 16 (94.1) | 34 (79.1) | 46 (56.8) | 96 (68.1) |

Figure 1. Comparison between unhealthy food/drink advertisements (high fat, sugar or salt) and target audience of television channel.

Figure 1. Comparison between unhealthy food/drink advertisements (high fat, sugar or salt) and target audience of television channel.

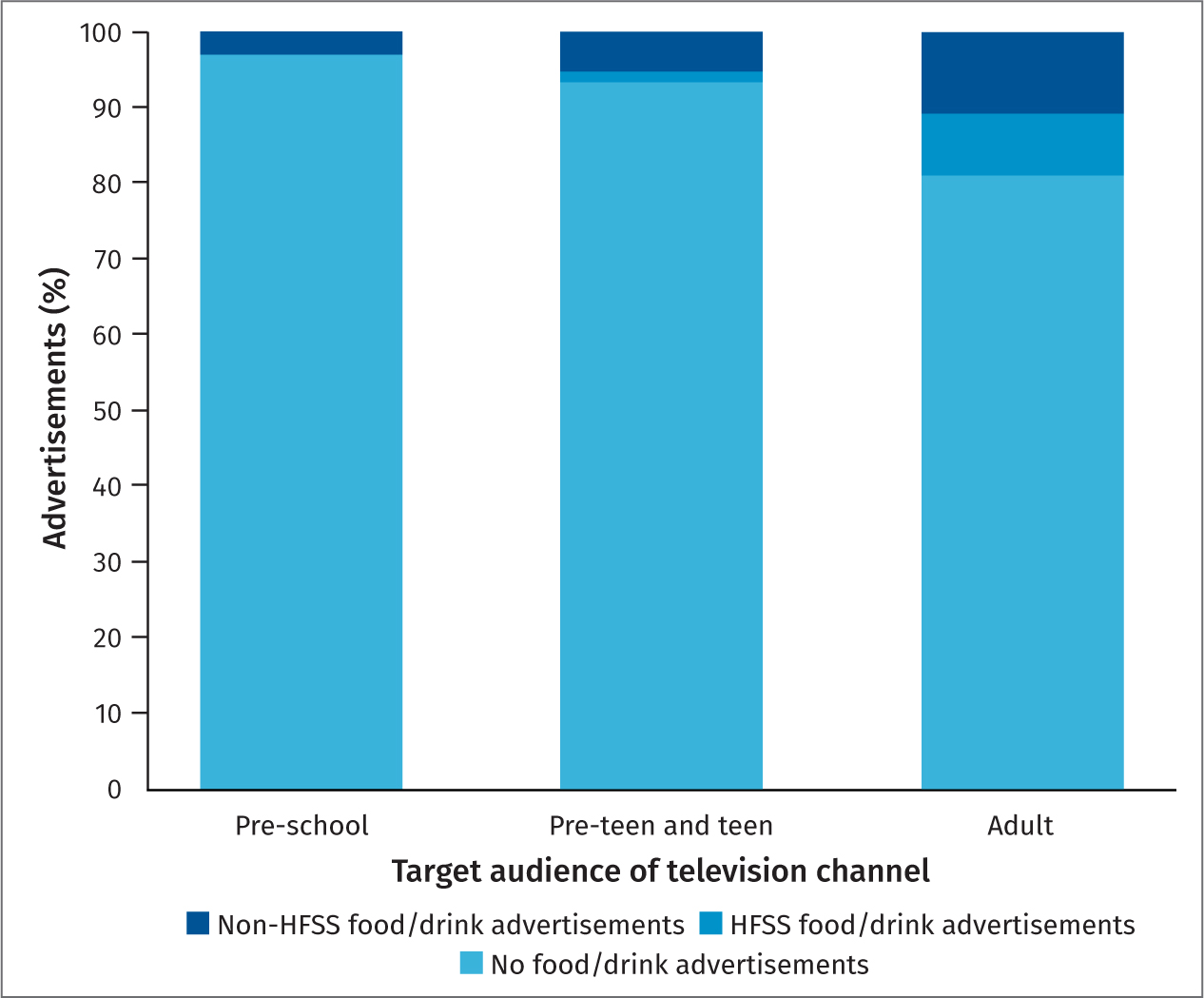

Although none of the food and drink advertisements broadcast on younger children's television channels were high in fat or salt, a small proportion of advertisements were high in sugar. Figure 2 illustrates how the proportion of different television advertisement categories varies according to the target audience of the television channel. Children who watch a greater proportion of adult television channels will be exposed to a significantly greater number of advertisements for HFSS products, with more than two advertisements for HFSS foods per hour.

Figure 2. Proportion of total advertisements made up by sub-categories, by target audience of television channel. HFSS=high in fat, salt or sugar

Figure 2. Proportion of total advertisements made up by sub-categories, by target audience of television channel. HFSS=high in fat, salt or sugar

Discussion

Statistics published by BARB and Ofcom were utilised to determine children's peak viewing times and select the most popular television channels with advertisements (Ofcom, 2017; BARB, 2020). Data collection took place over a 5-month period, on random days inclusive of weekend days and is thus representative of children's television viewing.

Just under one in ten (9.5%) advertisements were for food and drink products. This was less than previous studies; 34.8% found by Rodd and Patel (2005), and 16.4% found by Morgan et al (2009). There was also an apparent reduction in the frequency of HFSS product advertisements broadcast on children's television channels when compared against previous studies (Ofcom, 2010). This is an encouraging overall trend, but it is disappointing that a small number of HFSS product advertisements remained on channels targeted specifically to children. This is despite the regulations stating a blanket ban of HFSS advertisements on child-directed channels, suggesting that tighter enforcement of regulations is required.

Adult channels broadcast significantly more food and drink advertisements (4.8 per hour) in comparison to children's channels (1.0 per hour), with a significantly greater proportion of these advertisements being for HFSS products. The proportion of HFSS product advertisements was significantly greater (P<0.001) on channels targeted towards older children (20.9%) in comparison to those targeted towards younger children (5.9%). This may be indicative of advertisers' intention to exploit the greater independence of older children and teenagers in their access to money and ability to buy their products. The ongoing level of HFSS product advertisements broadcast on teen and adult channels is of concern. It has been recognised by Ofcom (2017) that children often access adult targeted television channels and airtime. To further limit child exposure to HFSS products, tighter regulations of advertisements on these channels must also be considered.

Despite offering a range of HFSS products, companies often only show healthy menu choices (non-HFSS) within their advertisements. Boyland et al (2015) concluded that advertisements drive an increased liking for the company in general, not for the healthier food choices. It appears that food companies can manipulate Ofcom's regulations, only advertising healthy products to satisfy Ofcom's requirements whilst still managing to promote the brand, in which the majority of products are HFSS. Theoretically, advertising healthier options should be viewed positively, but nevertheless it must be questioned and debated whether food companies should continue to be allowed to advertise to children without considering the potential health impact of their brand as a whole.

Any efforts to tighten regulations and reduce children's exposure to and consumption of HFSS products may be amplified by the provision of supplementary child and parent education on healthy dietary intake. Greater education and empowerment of parents in accessing and understanding government guidelines, such as the Eatwell Plate and of the Delivering Better Oral Health Toolkit, may be of benefit in allowing recognition and discounting of inaccuracies in advertisements (NHS, 2016; Department of Health, 2017). Though there have been inconsistencies in the reporting of the relationship between obesity and dental caries, the recurrent and undeniable theme is that there are common dietary risk factors, such as the increased intake of high sugar foods (Carson et al, 2017). Greater compliance with government guidelines may then be beneficial in managing both of these health threats.

Educational efforts were made by the FSA in their introduction of the traffic light system. This was developed as a guide for the public as to the fat, sugar and salt content of products by showing them to be either high (red), medium (amber) or low (green) per 100 g/100 ml of food/drink (Department of Health, 2016). The system was introduced in 2013 by the Department of Health and provides consistency, but it is used voluntarily and thus not currently adopted by approximately one-third of the food manufacturers/labels in the UK (Morrison, 2016). This is despite attempts by the Local Government Association to encourage mandatory use. The present study found inconsistencies in products not using the traffic light system, and variance in the recommended portion sizes for similar products, making comparison of nutritional value of food products difficult. Being able to easily compare how much fat, salt and sugar products contain is proven to be an effective way in helping people to actively make healthier choices (Sonnenberg et al, 2013). Improved labelling of products would enable parents to review products advertised on television more simply, helping consumers make healthier choices.

As further efforts are made to restrict HFSS advertisements on children's television programs, we must be mindful of marketer's reactionary utilisation of alternative media platforms. Online advertising of HFSS products has expanded greatly since the introduction of Ofcom's regulations in 2007 (ASA, 2018). This includes internet pop-ups, online games, and use of social media such as Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat. According to statistics from the Ofcom (2017) Media Use and Attitudes Report, 53% of 3–4 year olds, 79% of 5–7 year olds, 94% of 8–11 year olds and 99% of 12–15 year olds are now spending time online (Ofcom, 2017). Furthermore, 23% of 8–11 year olds and 74% of 12–15 year olds now own a social media profile (Ofcom, 2017). The recent rise in these figures has likely been driven by an increase in the usage of tablets and mobile phones, which permit online access by children.

With the majority of children now spending more time online, new challenges in managing advertisements have developed. Regulations have been introduced that prohibit HFSS advertisements on social media and websites targeted to children. However, since these rules were only introduced in July 2017, their effectiveness remains to be seen. There is currently much less evidence available regarding the influence that online advertising has on children's dietary intake in comparison to the strong evidence available for television advertising.

Conclusions

Despite the observed decline in advertisements for unhealthy products aired on children's television, healthcare professionals should remain mindful of the effect of frequent exposure of children to HFSS product television advertisements. Ensuring that legislation restricting unhealthy advertisements to children is upheld is important in reducing children's exposure to HFSS products. The findings of the present study show that children's exposure to HFSS television advertisements requires ongoing assessment in regard to the challenges of unhealthy diets, obesity and dental caries, and further regulatory interventions could be considered. The value of any such changes may be amplified further by development of new or greater access to supportive material and/or guidance for children and parents.

KEY POINTS

- Children's exposure to television advertisements can directly impact diet and has been recognised as a plausible determinant of child obesity

- Since the introduction of new regulations, the number of high fat, salt or sugar products advertised on children's television channels has reduced

- A statistically significant difference was found between the frequency of food and drink advertisements and the target age group of the television channel, with adult channels having a higher rate of these advertisements

- Of the high in fat, salt or sugar advertisements still broadcast on children's television channels, more were seen on channels aimed towards older children

- There is ongoing exposure of children to these products via both adult- and child-targeted television channels

- Ensuring that legislation restricting unhealthy advertisements to children is upheld is important in reducing children's exposure to high in fat, salt or sugar products

REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- Which of the proposed links between watching television and obesity do you believe to be the most significant, and why?

- Do current regulations on television advertisements go far enough to protect children from exposure to HFSS products?

- Should the same restrictions on advertising of HFSS products be applied to adult targeted channels as well as those targeted towards children?

- What do you consider to be the main challenges in regulating online advertisements of HFSS products?