Children make up 2.3 billion of the 7.8 billion people in the world (Fenz and Hamel, 2019; UN, 2019) and some of these children are orphans and vulnerable. Although there is no current data about the estimated number of orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) in the world, UNICEF (2017) estimated their number to be nearly 140 million in 2015. Africa is said to be home to 52 million of these orphans and vulnerable children (UNICEF, 2017).

The global occurrence and prevalence of adversities such as chronic poverty, acute and chronic illnesses, war, violence, conflict, road traffic accidents, HIV/AIDS (Arora et al, 2015; Kogo, 2018) and COVID-19 (Save the Children and UNICEF, 2020) have contributed to the increase in the number of orphans and vulnerable children. This increase constitutes a threat to the attainment of the Sustainable Developmental Goal 3 (Kogo, 2018). While it may be expected in some parts of Africa, especially in Nigeria, for children who lack parental care to be taken care of by the extended family, the high level of poverty, urbanisation and the high population of OVC have put a strain on the ability of some extended families to take up responsibility for the children who have lost their parents (Huynh et al, 2019). A significant proportion of such children therefore find solace in residential institutions such as orphanages (Assim, 2013; Huynh et al, 2019). Batha (2018) reported that 8 million children are estimated to live in orphanages and other institutions worldwide. This is almost four times what was reported 4 years earlier, where children in the orphanages were estimated at 2.2 million (FAI, 2014). In Nigeria, residential institutions such as orphanages are one of the most developed forms of formal alternative care available for children without parental care (Connelly and Ikpaahindi, 2016) despite its effect on children's social, emotional and cognitive development. In the context of new realities of family life in the study setting, the emergence of ‘social orphans’ is challenging. This concept is used to describe children who are neglected or abandoned by their own parents even though they are alive. Social orphanhood is associated with children suffering from parental negligence and deprivation due to their parents' failure or inability to perform their duties (Carter, 2017; Huynh, 2019). This ultimately creates peculiar vulnerability and further increases the number of children seeking refuge in residential care.

Despite a huge number of OVC living in orphanages and the concern about the care associated with residential care, their health status has rarely been documented in literature in the Nigerian setting. Studies have shown that children living in institutionalised settings are at risk of negative health and developmental outcomes (Desmond et al, 2020). In addition, a host of studies conducted among OVC in orphanages have also reported deficiency in their care (Lone and Ganesan, 2016; Nwaneri and Sadoh, 2016; Olagbuji and Okojie, 2016; Ramagopal et al, 2016; Mayuri and Ramya, 2017; Toutem et al, 2018). This deficiency in care requires an assessment of their health status in order to objectively determine potential or actual deficiency in their health status. This will serve as a basis upon which appropriate health intervention can be advocated for and provided. The purpose of this study was to document the morbidity profile and physical health status of Orphans and Vulnerable Children in selected Orphanages in Ibadan. In this study, physical health status is the status of the child based on the head-to-toe assessment and the body mass index.

Methods

This study employed a descriptive cross-sectional design. The target population are the OVC living in orphanages. The sample size was 384, using the Cochran formula n=Z 2pq/d2, with the prevalence rate (the proportion of OVC with poor health status) of 65% in a previous study (Ashly and Maheswari, 2017), and a 10% non-response rate.

The study employed a multistage sampling technique to select study participants. The first stage involved the selection of four local government areas (two urban and two suburban) from the 11 local government areas in Ibadan using a simple random sampling technique. The second stage involved a random selection of eligible orphanages (three from each of the selected local government areas) based on the inclusion criteria of being registered with the Ministry of Women's Affairs, being based in the state, being functional and having eligible children living in them at the time of the study. Selected orphanages were approached by the research team to discuss the purpose of the study and the selection of children. The third stage involved a random selection of eligible OVC (children or young people of less than 18 years with no major physical or congenital impairment).

Data collection

A pre-tested structured questionnaire was used to collect data directly from children who were 10 years and older, and from the caregivers of children under 10. The questionnaire has 3 sections. Section A contains questions on the socio-demographic characteristics of the OVC. Section B assesses the morbidity profile of the children and contains a list of common childhood illnesses experienced by the OVC in the last year with Yes or No options. Section C assessed the physical health status of the children and young people using a 53-item questionnaire. The first 52-item questionnaire is a physical examination checklist using the head-to-toe framework (adapted from Ashly and Maheswari, 2017) and one item assessed the nutritional status of the children using a BMI calculated from the height and weight. The BMI was interpreted using the NCHS and NCCDPHP (2000) BMI-for-age Children's Charts. The height was measured with a tape measure in centimetres and this was converted to metres. The steps followed for measuring the height were as described by Stephens (2019) while the weight was measured through the use of standardised weighing scales (in kilograms). The same scales and tape measure were used to assess the weight and height of all the children. The children's weight was measured with light clothing on and without footwear. The questions were translated into local languages to facilitate the participants' understanding of the concepts of the study and to be sure that they provide appropriate answers to each question (Wenz et al, 2021). The validity of this instrument was assessed through face validity and the reliability was obtained through a test–retest method with a correlation coefficient of 0.72. Data were collected between October 2019 and February 2020, directly from OVC aged 10 years and through their caregivers for children of less than 10 years. The decision was made based on the pilot study, where children aged 10 years and above responded to the questionnaire more appropriately while those below 10 years found it a bit difficult. However, all data were collected in the presence of the caregivers for all the children. All the distributed questionnaires were filled completely and retrieved because it was interviewer administered.

Data analysis

Data analysis was done with Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23 using descriptive and inferential statistics (Chi-square and multinomial logistic regression) at a 0.05 significance level. The morbidity profile data were presented using bar graphs. On the head-to-toe assessment, presence of abnormality was allotted 0 while absence of abnormality was allotted 1. For the BMI, abnormality (underweight, risk for overweight and overweight) was allotted 0 while normal BMI was allotted 1. The abnormality and normality of the BMI were judged based on the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) and National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP) (2000) BMI-for-age Children's Charts interpretation; a BMI inferior to the 5th percentile was categorised as underweight, a BMI between the 5th and 85th percentile as normal, superior to the 85th percentile as at risk for overweight and above the 95th percentile as overweight. The total obtainable mark for overall physical health status score was 53, which was converted to the percentile. The physical health status of each child was categorised based on the percentile score of the child. Any child that fell below the 50th percentile was categorised as poor, 50th to 75th percentile as fair and above the 75th percentile as good physical health status. A bivariate analysis was done between each of the socio-demographic characteristics of OVC and their physical health status using Chi-square test. Thereafter, significant socio-demographic characteristics from the Chi-square analysis were subjected to multivariate logistic regression analysis to identify the determinants of physical health status among the children.

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Ibadan University College Hospital Ethics Committee with approval number: UI/EC/19/0571. Approval was also obtained from the Ministry of Women's Affairs, Oyo State, to access the orphanages within the state, and informed consent of all participants was sought through consent and assent form signed by the participants. Consent was sought from their caregivers and/or proprietors of the orphanage for children in their facility to participate in the study while assent was asked from each child. All information gathered was treated with utmost confidentiality. The caregivers and the older children were duly informed of the purpose of the study and the benefits of taking part in the study. They were also informed that participation is voluntary and that they were free to choose whether they wanted to participate or that they could withdraw from the study anytime without any negative repercussions. To ensure the anonymity of the collected data, a unique identifier number was used on the survey instrument. Participants were also informed that the collected data would be kept confidential. Copies of the questionnaires and information sheets were kept in a locked file cabinet with the lead researcher.

Results

The socio-demographic characteristics of OVC

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. The mean age of respondents was 11.21±4.20, Min=3, Max=17. The largest proportion of the respondents (44%) was between the age of 11–15 years. There were more males (54.4%) than females (45.6%) among the respondents. About one third (37.5%) were at primary level of education while 40.9% were at secondary level of education. Many of the respondents (55.2%) were social- or non-orphans, the immunisation status of 66.9% of the respondents was not known and none of the respondents (0%) was under a health insurance scheme.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of OVC

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at last birthday | ||

| 1–5 | 58 | 15.1 |

| 6–10 | 92 | 24.0 |

| 11–15 | 169 | 44.0 |

| 16 and above | 65 | 16.9 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 209 | 54.4 |

| Female | 175 | 45.6 |

| Level of Education | ||

| Yet to start school | 16 | 4.2 |

| Kindergarten/nursery | 61 | 15.9 |

| Primary school | 144 | 37.5 |

| Secondary school | 157 | 0.9 |

| Not in school | 6 | 1.6 |

| Immunization status | ||

| Completed | 98 | 25.5 |

| Not completed | 29 | 7.6 |

| I don't know | 257 | 66.9 |

| Is this child under any health insurance scheme? | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0.0 |

| No | 384 | 100.0 |

Table 2 shows that almost half of the respondents (49.7%) were between the age of 1 and 5 years when they were admitted into the orphanage with a mean age of admission into the orphanage of 6.30±4.46 (Range 1–15) while the mean duration of stay in the orphanage was 4.93±3.74 (Range 3–15). Many of the respondents (62.5%) had stayed in the orphanage for a period of 1 to 5 years. Financial constraints of parents (48.4%) and maternal deaths (21.9%) were the major causes of residing in the orphanage. The majority of the orphans in the study were social orphans. The orphanage is responsible for the care of 91.2% of the respondents. The majority of respondents (94.5%) resided in a dormitory style of orphanage and the majority of the orphanages (49.4%) were private faith-based institutions.

Table 2. OVC Characteristics and type of orphanages

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age on admission into orphanage | ||

| 1–5 | 191 | 49.7 |

| 6–10 | 117 | 30.5 |

| 11–15 | 76 | 19.8 |

| Duration of stay in orphanage | ||

| 1–5 | 240 | 62.5 |

| 6–10 | 105 | 27.3 |

| 11–15 | 39 | 10.2 |

| Cause of stay in orphanages | ||

| Abandoned child | 14 | 3.6 |

| Broken home/parents' separation | 14 | 3.6 |

| Child trafficking/sexual abuse | 4 | 1.0 |

| Financial constraint of parents | 186 | 48.4 |

| Mother's illness | 4 | 1.0 |

| Mother's death | 84 | 21.9 |

| Father's death | 8 | 2.1 |

| Parents' death | 42 | 10.9 |

| Stubborn child/street child | 28 | 7.3 |

| AIDS orphans | ||

| Yes | 6 | 1.6 |

| No | 378 | 98.4 |

| Orphan status | ||

| Maternal orphans | 84 | 21.9 |

| Paternal orphans | 46 | 12.0 |

| Double orphans | 42 | 10.9 |

| Social orphans/non-orphans | 212 | 55.2 |

| Who is responsible for care? | ||

| Orphanage | 350 | 91.2 |

| Father | 19 | 4.9 |

| Mother | 8 | 2.1 |

| Relative | 7 | 1.8 |

| Style of orphanage where the child is residing | ||

| Family-based style | 21 | 5.5 |

| Dormitory | 363 | 94.5 |

| Type of orphanage where the child is residing | ||

| Government | 62 | 16.1 |

| Private | 133 | 34.6 |

| Faith-based private | 189 | 49.3 |

Morbidity profile of OVC

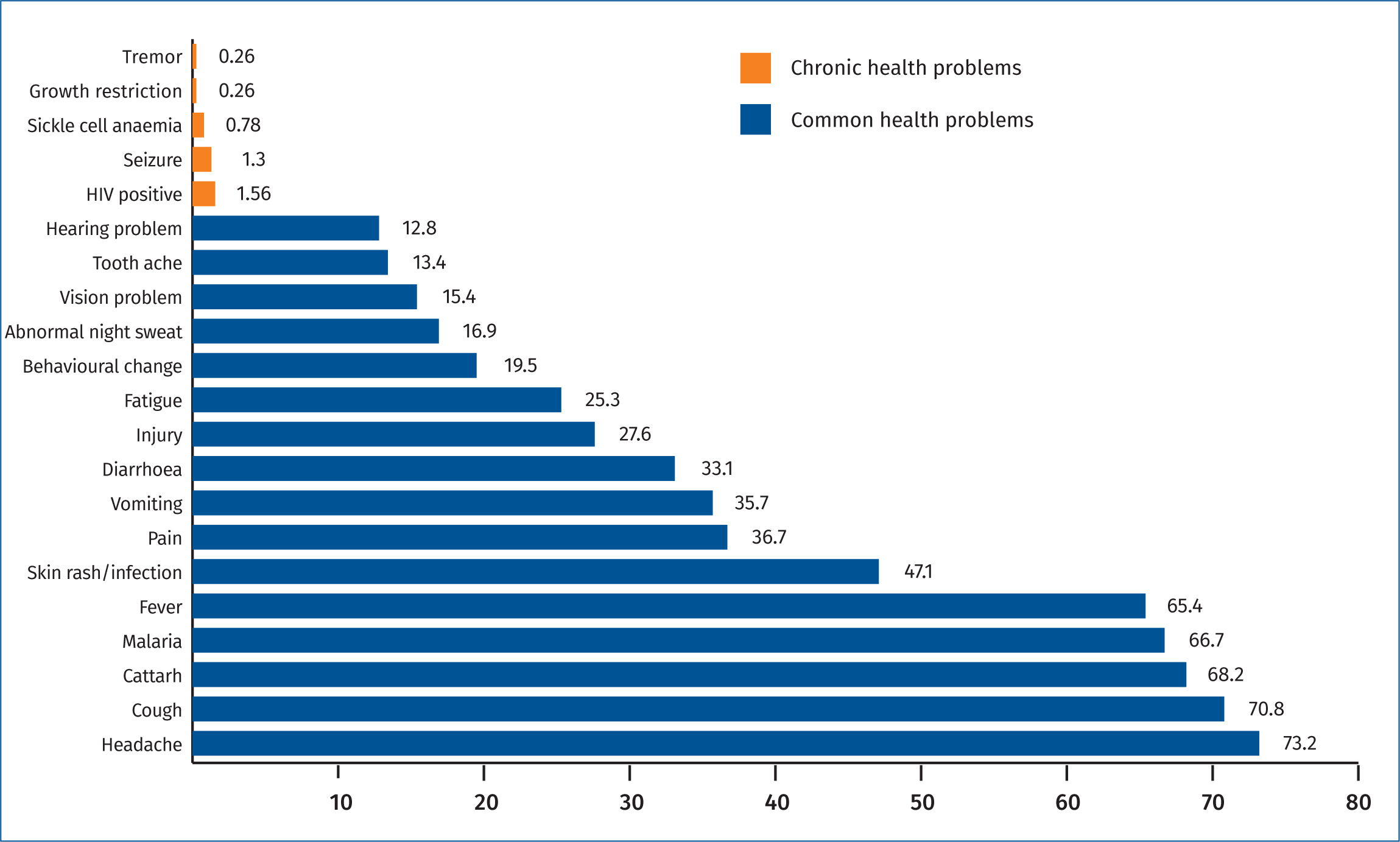

The result shows that the most prevalent childhood health problems experienced by children in the past year include headache (73.2%), cough (70.8%), catarrh (68.2%), malaria (66.7%) and fever (65.3%). The result shows that 4.2% (n=16) of the children have a chronic medical condition or disability, and HIV infection was the most prevalent chronic health problem among the children (1.56%, n=6). The majority (95.8%) of children did not have any chronic medical condition or disability. Figure 1 shows the morbidity profile of OVC as reported by the children and caregivers.

Physical health status of OVC

The mean health status score using the head-to-toe assessment was 49.34 ± 2.11; minimum score = 40.00 and maximum score = 52.00. The result of the head-to-toe assessment reflects a fair picture of the physical health examination for children in a residential facility. The mean BMI score was 16.64 ± 2.66; minimum score 8.00 while the maximum score was 32.70.

Table 3 shows the summary of the nutritional status of OVC using their BMI. Many of the respondents (76.9%) were underweight, 21.6% had normal weight, 1.0% were at risk of overweight and 0.5% were overweight.

Table 3. Nutritional health status of OVC

| Variables | Frequency N=384 | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Height (M) | ||

| 0.10–1.00 | 35 | 9.1 |

| 1.01–2.00 | 349 | 90.9 |

| Mean±SD: 1.42±0.87 | ||

| Weight (Kg) | ||

| 0–20 | 77 | 20.1 |

| 21–40 | 213 | 55.5 |

| 41–60 | 89 | 23.2 |

| 61–80 | 5 | 1.3 |

| Mean±SD: 31.87±12.79 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| Underweight | 295 | 76.9 |

| Normal weight | 83 | 21.6 |

| Risk for Overweight | 4 | 1.0 |

| Overweight | 2 | 0.5 |

| Mean±SD: 16.64±2.66 | ||

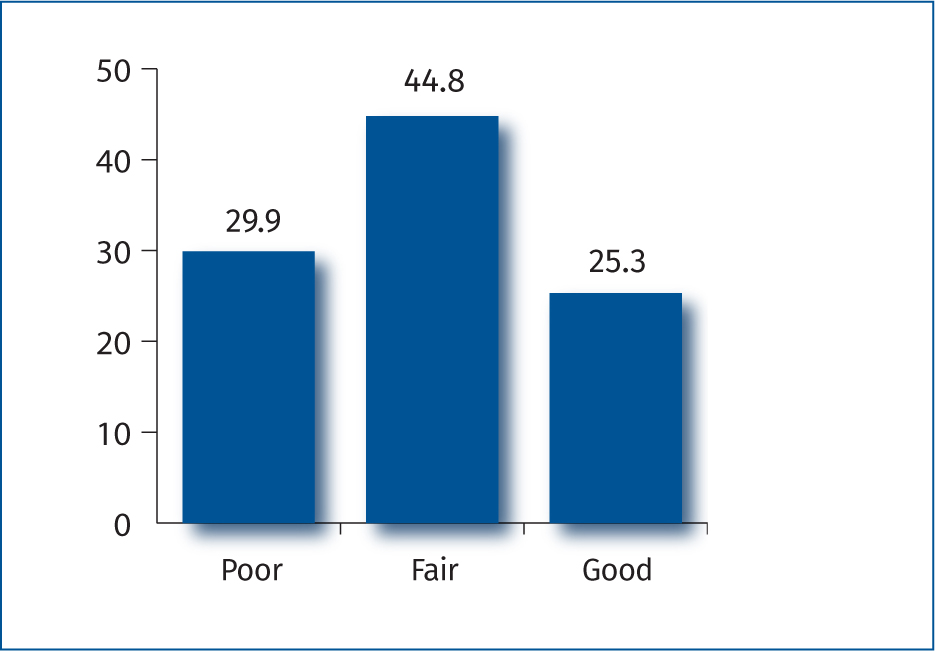

Figure 2 shows the summary of the overall physical health status of OVC using percentiles. The result shows that 44.8% had fair physical health status while 29.9% and 25.3% had poor and good physical health status respectively.

Characteristics predicting physical health status

Table 4 is the logistic regression of the socio-demographic and orphan characteristics of OVC and the physical health status. Table 5 shows that orphans and vulnerable children who are 10 years and above were about two times more likely to have good physical health than children who are below 10 years of age (p<0.05, Odd ratio–2.02, CI 1.56–9.29). In the same vein, orphans and vulnerable children in secondary level of education were about three times more likely to have good physical health than OVC who are not in school (vocational training) (p<0.05, Odd ratio-2.56, CI 1.82–7.07). The result also showed that the likelihood of having good physical health status decreased by 68% among female OVC when compared to their male counterparts (p<0.05, Odd ratio – 0.32, CI: 0.18 – 0.57).

Table 4. Multinomial logistic regression analysis of factors that influence physical health status Of OVC

| Variable | Statistical significance | Odds ratio | Confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower level | Upper level | |||

| Age | ||||

| 1–9 | 1 (ref) | |||

| 10 and above | 0.04* | 2.02 | 1.56 | 9.29 |

| Age when admitted into the orphanage | ||||

| 1–5 | 1 (ref) | |||

| 6–10 | 0.45 | 0.49 | 0.07 | 3.09 |

| 11–15 | 0.72 | 1.21 | 0.40 | 3.66 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1 (ref) | |||

| Female | 0.01* | 0.32 | 0.18 | 0.57 |

| Duration in orphanage | ||||

| 1–5 | 1(ref) | |||

| 6–10 | 0.70 | 1.57 | 0.15 | 16.43 |

| 11–15 | 0.88 | 0.93 | 0.36 | 2.41 |

| Above 15 | 0.11 | 5.81 | 0.64 | 52.52 |

| Level of Education | ||||

| Yet to start school | 0.17 | 0.33 | 0.68 | 1.61 |

| Kindergarten | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 1.13 |

| Nursery | 0.12 | 3.81 | 0.69 | 20.89 |

| Primary | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.37 | 2.41 |

| Secondary | 0.03* | 2.56 | 1.82 | 7.07 |

| Not in school | 1 (ref) | |||

| Orphan status | ||||

| Maternal orphans | 0.59 | 0.83 | 0.42 | 1.63 |

| Paternal orphans | 0.73 | 0.86 | 0.37 | 1.99 |

| Double orphans | 0.45 | 0.71 | 0.29 | 1.71 |

| Social orphans/non-orphans | 1(ref) | |||

| Immunisation status | ||||

| Completed | 0.54 | 1.23 | 0.57 | 2.87 |

| Not completed | 0.16 | 3.49 | 0.60 | 20.35 |

| I don't know | 1 (ref) | |||

Discussion

The study assessed the morbidity profile and physical health status of the OVC in orphanages. The distribution of the subjects by age revealed that many of the participants (OVC) were within the age range of 11–15 with a mean age of 11.21±4.20. This is at variance with a study conducted in India by Ashly and Maheswari (2017) in which many of the participants were 9 years old. Furthermore, there were more males than females among the participants in this study. This is consistent with previous studies conducted in Bangladesh and Nigeria (Huq et al, 2013; Ishaya et al, 2016). The finding is, however, at variance with previous studies conducted in Nigeria (Olagbuji and Okojie, 2016) where males and females were found to be of equal proportion; and in India (Ashly and Maheswari, 2017) where there were more females than males.

The findings revealed that more than half of the OVC in the orphanages were social or non-orphans and the major cause of their stay in orphanages was the financial constraint of their parents, followed by maternal death. The economic hardship in the country has made some parents take their children to orphanages and transfer their parental roles and responsibilities to caregivers. The African pride of parenting has been compromised because of lack of money and inability to provide for the needs of the children (Pillay, 2016; Nar, 2020). These findings are consistent with a study by Connelly and Ikpaahindi (2016) who identified poverty and loss of parents as major causes of admission of children into childcare institutions. The findings are also in line with the submission of Olowokere and Okanlawon (2016) who also stated poverty and loss of parents as major causes of orphanhood and vulnerability. However, this is at variance with a study conducted in Bangladesh by Huq et al (2013) who reported educational purpose as the reason why many OVC in their study were in the orphanage. Also, just a quarter (25.5%) of the OVC completed their immunisation. This proportion of children who completed their immunisation schedule is low when compared with a study from Kenya where many of the OVC in the orphanage completed their vaccination (Mwaniki et al, 2014). The lack of vaccination against childhood diseases can put the children at risk of childhood illnesses and will consequently increase the morbidity and mortality rate among this vulnerable population (CDC, 2019). Immunisation has been identified as the most cost-effective health investment, averting about 2–3 million deaths each year (WHO, 2019). This also reiterates the importance of healthcare providers' outreach programme to the orphanages where children in orphanages are properly assessed for age-appropriate immunisations. The study revealed that none of the OVC was under health insurance, which implies expenses on their health will be out-of-pocket, expensive and may likely be unaffordable. This may negatively impact on the decision to seek medical care when ill. This finding corroborated the study by George et al (2018) who identified lack of health insurance as a major barrier to meeting healthcare needs among vulnerable populations.

The morbidity profile of the children showed few (4.2%) of the children have chronic illnesses such as sickle cell anaemia, seizure disorder, growth retardation, HIV infection and tremor. The findings were at variance with a study by McSherry et al (2015) where close to one third of children surveyed was suffering from a chronic illness and/or disability. Despite the fact that the number of children living with chronic illnesses are few in the current study, the numbers are significant enough to receive optimal attention. There is a need to appropriately support the children so they can live positively with chronic illnesses in the best physical health possible. The implication of this finding is that healthcare workers and especially nurses need to monitor, educate, train and support the proprietors and caregivers on how to care for such children and how to seek expert care when necessary (Frood et al, 2018). The care of these children will also benefit from facilitative supervision by health professionals. Furthermore, caregivers in orphanages and HIV-positive children would benefit from healthcare providers' support on how to prevent, treat and cope with HIV and associated complications. More importantly, HIV-positive children need information for self-care and protection, and support to avoid transmission to other children (Frood et al, 2018).

Many of the common morbidities experienced by the children in the current study are similar to the report of Toutem et al (2018) in a study conducted in Southern India. Worthy of note is the proportion experiencing headache, cough, catarrh, malaria, fever and skin infections. These problems are suggestive of the need for periodic and regular visits to the orphanages by healthcare providers to assess and identify factors within the orphanages that could be contributing to health problems among OVC (El-sherbeny et al, 2015). Provision of appropriate healthcare for OVC is critical for maximising their health, potential and quality of life (Britto et al, 2017; Pillay, 2018). Healthcare providers need to be more proactive to engage in periodic community outreach programmes that focus on health assessment and prompt treatment of health problems for these children.

The findings from the physical assessment show that a significant proportion of OVC have decayed tooth and skin infections such as eczema, scabies, ringworm and rashes. This finding is consistent with the findings of Mayuri and Ramya (2017) who reported skin and dental problems as leading morbidities observed among children living in orphanages in India. This may likely be due to the non-individualised care that the children tend to receive from the caregivers in the orphanage. Dormitory style orphanages have been characterised by a low ratio of caregivers to children and a lack of individualised care for children (Embleton et al, 2014; Faith to Action Initiative, 2014; Darkwah et al, 2018).

Other abnormalities found to be existing among the children include redness or yellowness of sclera, pale conjunctiva, discharge and pain in the ear, impaired hearing, running nose, bad breath, bleeding from the gums, inflammation of the tonsils, cough and wounds on the scalp and extremities. These findings are almost in line with the findings of Toutem et al (2018) in a study conducted in Southern India. The understanding of the common health problems among OVC in the orphanages will help healthcare providers, most especially nurses, to know essential drugs and resources that will be needed to respond to the common health challenges of OVC. This is because the care of children in residential settings like orphanages is within the scope of public health nursing.

The nutritional assessment (BMI) also shows that the majority of children are underweight. This is of concern because poor nutritional status can make them vulnerable to infection and illnesses (Alemu, 2020, Gwela et al, 2019). This finding is consistent with that of Huq et al (2013) and that of Ashly and Maheswari (2017) who reported that the majority of children had malnutrition, but in contrast to Olagbuji and Okojie's study (2016) which reports that only a few are underweight. The findings of the current study show that more attention needs to be paid to the nutritional care of children and young people in the orphanages. This is because a scientific report has identified malnutrition as the key underlying and sensitive risk factor of vulnerability to an early grave among children (WHO, 2018. Therefore, good nutrition is pertinent for the children's continual existence and physical development (Chulack, 2016; Children's Bureau, 2018; Karratti, 2018). Combining direct food supplements with the linkage of orphanages to economic strengthening programmes, which empowers orphanages to improve their resource mobilisation ability, may assist them to meet the nutritional needs of the children in the orphanages and therefore improve their nutritional status. Healthcare workers may also help build the skills of caregivers at orphanages in meal planning, food preparation and food purchasing to help them feed the children adequately (Grobbelaar and Napier, 2014; Oduor et al, 2019; Samuel et al, 2021).

The overall physical health status of about one third of the OVC was poor, while the largest proportion had fair overall physical health status. This finding was in contrast to the study conducted in India by Ashly and Maheswari (2017) where a majority of OVC in their study have poor physical health status. The reason for the lower proportion of children with poor health status in the current study, in comparison with the study in India, could be because most of the orphanages were faith-based institutions that receive donations (cash or food) from philanthropists and significant members of the community. This may be enhancing their capacity to support the children.

The multinomial logistic regression predicting likelihood factors that influence physical health status in Table 5 shows that orphans and vulnerable children who are 10 years old and above, and those at the secondary level of education, are about two times and three times more likely to have good physical health status respectively, when compared with OVC below 10 years of age and those who are not in school. This is likely because most OVC who are 10 years old and above, and those at secondary level of education, are mature enough to take care of themselves and at the same time have a strong concern for their appearance (Juli, 2017). Also, the need to look attractive especially to the opposite sex among adolescents may make them place premium attention on their self-care as well as their overall physical health. This finding has implications for caregiving by healthcare providers. It is necessary to pay closer attention to children below the age of 10 and to those who are not in school so as to monitor their health and to support their self-care practices.

Implications for practice and further study

The policy-makers and concerned stakeholders, especially nurses, the government, and non-governmental organisations should strategise, design and implement appropriate interventions to help improve the health status of OVC in Nigeria. Taking a clue from countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States of America, healthcare workers like nurses are usually involved in providing care for children in orphanages. They provide a range of comprehensive healthcare services for children (Department for Education and Health, 2015; RCN, 2015, Szilagyi et al, 2015). Regular home visits to orphanages by healthcare professionals, especially public health nurses, are recommended. This will aid transference of appropriate health-related knowledge from nurses to children and their caregivers. For example, healthcare providers could provide a range of services to continually address nutritional problems in the orphanages through nutritional counselling, helping orphanages to provide nutritional supplements for the children and linking orphanages to food security or economic strengthening programmes in the community. Proprietors of orphanages could be linked with appropriate support services within the community to enhance their capacity to cater for the wellbeing of children under their care. This study has objectively documented the morbidity profile and physical health status of OVC in orphanages. Further study might replicate this study among OVC that live in more orphanages, households and those with foster parents.

Limitations

Some information about the children was obtained through the help of their caregivers. This is because some of the children were young and were not able to give adequate information about themselves, but caregivers' responses could be prone to bias. However, the physical health assessment that was done by the researchers provided objective information about the health status of OVC. In addition to this, inference on causal relationships cannot be made because of the design of the study.

Cconclusions

A significant number of OVC in orphanages have fair and poor physical health status. There are few children and young people in the orphanages that are living with chronic illnesses, while most of them are underweight. There is therefore a need for comprehensive health service provision for these children by healthcare workers so as to continually improve their health status and to avert future morbidity and consequent mortality. There is need for policy formulation and implementation as regards provision of healthcare services for OVC in the orphanages. This is necessary because there is no policy that specifically addresses provision of healthcare services for this category of children, unlike in other countries like the United Kingdom and the United States (Department for Education and Health, 2015; RCN, 2015; Szilagyi et al, 2015). Despite health and developmental problems associated with orphanages, many OVC still live in residential care. Their health must not be neglected as long as they live in the orphanages. There is a need to continually monitor their health status to ensure timely and appropriate care is given for optimal health.

KEY POINTS

- The majority of children in the orphanages are social orphans

- A significant proportion of OVC have poor physical health

- The majority of OVC in the orphanages are underweight

- Food security for orphanages should be addressed in health programming for vulnerable children in residential care.

REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- Why is a study which focuses on the assessment of health status of orphans and vulnerable children important?

- Why did the researchers focus on orphans and vulnerable children living in orphanages?

- What are the three most common childhood health problems experienced by the children who participated in this study?

- Which social demographic characteristics of OVC will predict their physical health status?