Body image has been a focus of interest among societies and scientific communities through the ages, and during the first decade of this century there has been an increase in the number of studies on the subject (Cash and Smolak, 2012). Body image is not just the construction of an individual perception, but also a reflection of the interactions with others (Schilder, 1950).

In toddlers (children between 12 and 36 months), due to their age, the concern with body image is mainly reserved to their parents. The ideal they have about the child's weight and body shape may be influenced by family, society, culture and the child's gender, among other aspects. Cultural prejudice favours thinness and is against excess weight. For the feminine gender, the ideal is a thin body, while for the masculine it is a thin and slightly muscled body. A deviation from this ideal may imply negative social consequences (Grogan, 2017).

The World Health Organization (WHO) says that overweight and obesity are associated with more deaths in the whole world than underweight, and estimates that 38 million under-5-year-old children were overweight or obese in 2009 (WHO, 2020). Excess weight in this age group may persist in adolescence, increasing the risk of comorbidities associated with obesity in adulthood (Sahoo et al, 2015).

Family has a big influence on children's lifestyle (Scaglioni et al, 2011; Alm et al, 2015), being their first reference model, including on eating habits (Sahoo et al, 2015; Berggren et al, 2018). Healthy eating in childhood is important, not only to prevent diseases associated with bad eating habits, but also because the eating habits acquired in this stage of life usually persist during a whole lifetime (Sahoo et al, 2015). Assessing children's nutritional status is of the utmost importance, since it allows us to monitor their development and detect and address changes that may negatively affect their current and/or future health (e.g. under or overnutrition) (Black et al, 2013). In toddlers, the identification of the nutritional status is fundamental to implement nutritional prevention or correction strategies (Hager et al, 2010). It also allows health professionals to plan effective interventions in order to reestablish the ideal health status, minimising the damage caused by underweight, overweight or obesity (Santini and Kirsten, 2012). The parents' importance in the development of eating habits and the recognition of their children's nutritional status is acknowledged, but there are studies (Berggren et al, 2018) which alert to the fact that they are not entirely capable of identifying their children's excess weight. Parents' perceptions about the children's growth status, height and weight (below or above the weight which is considered normal for the age and sex) are key factors in the family's determination and readiness to change lifestyles, since to implement behaviour changes related to health, the health issue has to be acknowledged first (Ling et al, 2018). Therefore, parents who do not acknowledge that their children are overweight have less probability of being concerned about their health and adopting healthier habits (Brown et al, 2016).

Health professionals' guidance may assume a fundamental role so that parents recognise their children's nutritional status and promote healthy behaviour (Dinkel et al, 2017). This means that during the child's surveillance appointments, health professionals, namely nurses, have the responsibility of informing them about their child's nutritional status and discuss the appropriate growth patterns with them, doing more than simply informing them about the growth curves (Brown et al, 2016). The paediatric Silhoutte Scales are a tool which can be used by nurses to help parents identify their children's nutritional status. With that in mind, this study has been developed to assess parents' perception about their toddler's nutritional status.

Methods

Quantitative, descriptive and relational study on a population of toddlers' parents who attended nurseries in the district of Viseu, Portugal. The 94 institutions in the district have been contacted, 68 of them having agreed to participate in the study. The data collection has been conducted between November 2018 and September 2019 through a survey answered by the parents. Of the 2 036 surveys given to all the parents of the registered children, 828 were returned. Twenty surveys were excluded for not containing all the information about the child's weight, length or age, resulting in a non-probabilistic sample consisting of 808 toddlers' parents.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants had to be the father or mother of a toddler who attended a nursery in the district of Viseu and who did not suffer from chronic diseases which might directly interfere on the nutritional status. Participants had to sign a form of informed consent.

Instrument of data collection

A survey which included a group of questions about the characterisation of the children (age, gender, weight and length, based on the last entry on the Child and Youth's Health Bulletin), questions about the Health Care Center's appointments (alerts from the professionals about changes in the child's weight) and ‘Toddler Silhouette Scale’ developed and validated by Hager et al in 2010 for children aged between 12 and 36 months regardless of gender or ethnic background. The scale may be used in clinic contexts to assess parents' perception and satisfaction with the size of the child's body, and with research goals. It is comprised of seven pictures, picture 1 corresponding to underweight, pictures 2 to 5 to normal weight and pictures 6 and 7 to overweight. Parents were asked to mark the picture which corresponded to the silhouette they considered ideal for a child their child's age (ideal silhouette) and, also, the silhouette they believed to correspond to their child's present silhouette (real silhouette).

Data analysis and processing

The data were processed through IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 25. Data approach involved simple descriptive statistical analysis (average, deviation, pattern and percentage). A possible connection between nutritional status and body image has been explored by conducting the chi-square test (X2), or Fisher's exact test. For the average comparison, the parametric test (t-test) has been used. In all analyses, the statistic significance was accepted for p values <0.05 and adjusted residuals ≥1.96. The use of residual values in nominal variables is more potent than the X2 test, since the adjusted residuals inform about the cells that are most distant from the independence between the variables (Marôco, 2018).

For the diagnosis of the children's nutritional status, the WHO international criteria (WHO, 2006) about the BMI percentile (Body Mass Index) were used considering: <3 percentile diagnosis underweight; ≥3 percentile and <85 normal weight; ≥85 percentile and <97 overweight; and ≥97 percentile obese. Children's BMI (difference between weight and height square) was calculated based on the last entry on the Child and Youth's Health Bulletin, assessed in the health care center's appointment, considering the child's age at that moment.

Ethical aspects

The study has been approved by the Ethical Commission (CETI) of the Abel Salazar Biomedical Sciences Institute (Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas Abel Salazar), Porto University (Universidade do Porto) (n.° 263/2018/CETI) and authorised by the directors of the nurseries in which it was conducted. All the participants signed an informed consent form.

Results

Sample comprised of 808 toddlers' parents (confidence interval of 3% for a level of significance of 95%). Most toddlers (50.4%) were male, 46.5% were between 12 and 23 months old, 44.1% between 24 and 35 months old, and 9.4% were 36 months old (M=24.63; SD=7.24). The weight varied between 6.8Kg and 21Kg (M=11.80; SD=1.92) and the length between 47 cm and 104 cm (M=84; SD=0.07), 0.7% were underweight, 21.8% overweight and 9.8% obese (Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution of the characteristics of the sample

| Children | average (SD) | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | 24.63 (7.24) | ||

| Gender | Male | 407 (50.4) | |

| Female | 401 (49.6) | ||

| Weight (kg) | 11.80 (1.92) | ||

| Length (cm) | 84 (0.07) | ||

| Percentile of current weight | Underweight | 6 (0.7) | |

| Normal weight | 548 (67.8) | ||

| Overweight | 175 (21.8) | ||

| Obese | 79 (9.8) |

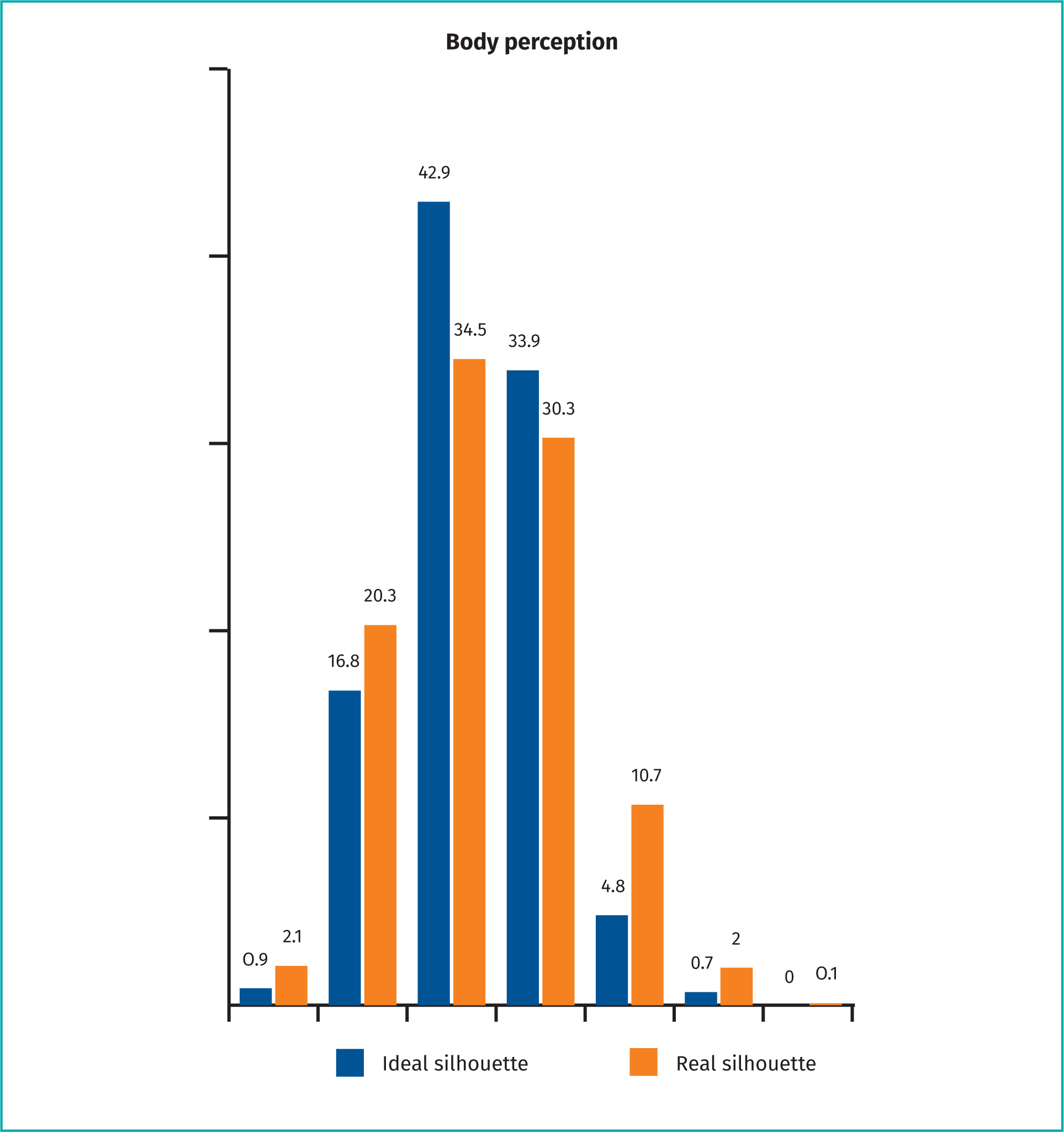

It has been verified that most parents (98.4%) considered that the ideal silhouette for a child their child's age was the one corresponding to the normal weight (pictures 2, 3, 4 and 5). While for 0.9% it was the silhouette corresponding to underweight (picture 1) and for 0.7%, the silhouette related to overweight (picture 6) (Figure 1).

Most parents (95.8%) considered that their child's real silhouette corresponded to the one of normal weight (pictures 2, 3, 4 and 5), 2.1% to the one of underweight (picture 1) and 2.1% to the one of overweight (pictures 6 and 7) (Figure 1).

The differences between the silhouettes perceived by parents as ideal and real have proven statistically significant (p=0.005); which shows that parents perceive that their children have one silhouette when in fact they have a different one with a variable of >60% (Table 2).

Table 2. Results of the t-test between ideal silhouette and real silhouette perceived by parents

| Difference | t | r | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| -0.066 | -2.833 | 0.780 | (**) |

Abbreviations: p=t-test

**p<0.01

The data concerning the toddlers' BMI percentile (Table 3) at the date of the study show that the majority (67.8%) had a normal weight. Among the children who were aged between 24–35 months, 23.0% were overweight and 6.7% obese. Statistical significances (p=0.046) have been found between the groups, localised by the adjusted residuals, between toddlers aged 12 and 23 months and the ones with obesity (Table 3).

Table 3. Child's BMI percentile regarding age and parental perception of the real silhouette

| BMI | Underweight | Normal-weight | Overweight | Obesity | Total | Residual | P | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentile | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Variables | (6) | (0.7) | (548) | (67.8) | (175) | (21.7) | (79) | (9.8) | (808) | (100) | |||||

| Child's age | |||||||||||||||

| 12–23 months | 3 | 0.8 | 242 | 64.4 | 82 | 21.8 | 49 | 13.0 | 376 | 46.5 | .2 | -2.0 | .1 | 2.9 | (*) |

| 24–35 months | 2 | 0.6 | 248 | 69.7 | 82 | 23.0 | 24 | 6.7 | 356 | 44.1 | -.5 | 1.0 | .8 | -2.6 | |

| 36 months | 1 | 1.3 | 58 | 76.3 | 11 | 14.5 | 6 | 7.9 | 76 | 9.4 | .6 | 1.7 | -1.6 | -.6 | |

| Parental perception of the real silhouette | |||||||||||||||

| Underweight | 2 | 11.8 | 9 | 52.9 | 4 | 23.5 | 2 | 11.8 | 17 | 2.1 | 5.4 | -1.3 | .2 | .3 | (***) |

| Normal-weight | 4 | 0.5 | 536 | 69.3 | 164 | 21.2 | 70 | 9.0 | 774 | 95.8 | -3.6 | 4.1 | -1.5 | -3.3 | |

| Overweight | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 17.6 | 7 | 41.2 | 7 | 41.2 | 17 | 2.1 | -0.4 | -4.5 | 2.0 | 4.4 | |

Abreviations: BMI: Body Mass Index; p= Fisher's exact test

***p<0.001,

*p<0.05

Comparing real silhouette perceived by parents, with the toddlers' BMI percentile, it has been concluded that the majority of the children (69.3%) whom the parents considered to have a silhouette corresponding to a normal weight, had in fact a BMI percentile corresponding to a normal weight. For toddlers whose parents considered the real silhouette corresponded to overweight, it has been found that 41.2% had a BMI percentile equivalent to overweight and 41.2% to obesity (Table 3). Fisher's test result revealed statistically significant differences between groups (p=0.000), and the adjusted residuals indicate a tendency for parents to have a perception of the child's real silhouette that corresponds to the child's BMI percentile (Table 3).

Among the parents of children who presented a BMI percentile corresponding to underweight, 33.3% have mentioned having been alerted by professionals from the health care center to that fact. 31.4% parents of toddlers with overweight and 1.3% of the ones who had obese children also said they had been alerted (Table 4).

Table 4. Alert about the weight change at the health care centre's appointments and parents' attitude regarding that alert

| Alert about the weight change at the Health Care Center appointments | Yes |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Underweight children | 2 (33.3) |

| Overweight children | 55 (31.4) |

| Obese child | 1 (1.3) |

None of the parents of toddlers who were underweight or obese and had been alerted by the nurses from the health care center concerning that issue have implemented any change concerning their children's eating habits or physical activity, the same having been verified with 9.7% of the parents of the overweight children. However, 13.7% of the parents of overweight children have changed the amount of food given to their children and 2.9% have changed the physical activity (Table 4).

Discussion

Concerning the present study, the assessment of parents' perception about the toddlers' nutritional status has been conducted by using the Hager et al Silhouette Scale (Hager et al, 2010). Data revealed that most children had a normal weight. However, 0.7% were underweight and 31.5% weighed more than what is considered ideal for their length and gender (21.7% overweight and 9.8% obesity). Other studies which have used the same scale have concluded that most toddlers had a normal weight (Hager et al, 2012; Adeniyi et al, 2018). The percentage of underweight children in our study was inferior to the one presented in those studies (Hager et al, 2012; Adeniyi et al, 2018), and the number of overweight toddlers was superior to the one presented by Adeniyi et al (2018). The percentage of obesity was inferior to the one reported by other researchers (Hager et al, 2012). This fact may be due to the social and economical characteristics of the places and communities where the studies were made.

Considering parental perception about their children's silhouette, it has been verified that most parents perceived their child's real silhouette as corresponding to pictures of a normal weight, however, by analysing the toddlers' BMI percentile at the moment of the study, it has been verified that some of those perceptions did not correspond to the actual weight of the child. These results corroborate the ones from other researchers. A study conducted with 897 mothers of less than 5-year-old Indian children (Dalal et al, 2019), found that 50% of the mothers were not able to understand the status of their child's correct weight. Adeniyi et al (2018) verified that all the overweight children were classified erroneously by the parents as having a normal weight. A study conducted in Portugal with 313 children aged between 2 and 6 years old, has revealed the absence of parental perception about their children's excess weight (Gomes et al, 2010).

Regarding the silhouette scale, the results of this study corroborate the ones obtained by the authors of the scale who have concluded that even though some parents have difficulties in identifying their children's real silhouette, the majority are able to correctly identify the silhouette which corresponds to their child's real weight (Hager et al, 2010). The scale is thus considered to be a useful instrument to help parents assess their children's nutritional status.

It has been verified that toddlers' parents have not always been alerted by nurses or doctors in the Health Care Center during their children's surveillance appointments about the fact that they presented a BMI corresponding to underweight, overweight or obesity, which concurs with the results gathered by Brown et al (2016). The difficulty many parents have to identify whether their child is underweight, overweight or obese, associated with the non-communication of that status by the nurses and doctors responsible for the child's health surveillance may lead them not to implement preventive or control measures of those situations. The fact that parents do not implement changes in the children's eating habits and physical activity when they are alerted by the health Care Center professionals about deviations on their child's percentile leads us to consider the importance of a bigger investment of the nurses in the toddlers' parents' health education.

Limitations

In spite of the fact that the study contributes to the knowledge about parents' perception concerning their children's nutritional status in the toddler stage, and although a validated visual scale has been used, the results cannot be generalised to the Portuguese population due to the fact that the study is limited to a single district of the country.

Implications for practice

The findings of this study allow us to conclude that parental perception about toddlers' nutritional status is often erroneous, which may cause the non-identification of problems related with the children's weight and cause a delay in the reaction. It is relevant to conduct studies which may allow us to identify which variables interfere with the parents' erroneous perception.

It has also become obvious that the parents have considered not to have been alerted by the nurses during the child's surveillance appointments about their child's nutritional status not being appropriate for their age and gender, nor about the potential implications that the situation might have on the child's health. This stresses the need for nurses to pay more attention to this issue, to act assertively, systematically including this subject in all the surveillance appointments and in the educational actions for health they conduct for toddlers' parents. Parents' perception about their children's unhealthy weight and the understanding of the consequences for their health are key factors for the nurses to address, with the child's health in mind.

Conclusions

The perception and parental knowledge about their children's overweight, obesity or underweight are essential for parents to be able to adopt measures in order to prevent and correct these situations. The existence of an inaccurate parental perception about their children's body and weight has been verified. This lack of perception may be associated with the perpetuating of unhealthy family habits and may limit the adoption of preventive measures. Nurses must pay attention to this situation, inciting and helping parents to adopt healthy lifestyles and prevent overweight and child obesity.

The present study contributes to research and the clinical nursing practice by contributing to a bigger understanding of the toddler's parents' perception about their child's nutritional status, underlining the benefits of using appropriate instruments to assess parents' perception.

With regard to the clinical practice, the results suggest that even though the nurses have the competence to accurately assess the children's nutritional status, they are not always alerted to the importance of warning parents about that nutritional status. This study emphasizes the need for nurses' awareness of the relevance of assessing the children, giving the appropriate information to the parents, and encouraging the implementation of strategies which promote the adoption of healthy lifestyles in the family.

KEY POINTS

- Parents' perception about the changes in the child's BMI is a key factor for the adequacy of children's diet and physical activity.

- The perception that parents have about the silhouette of their children may depend on the child's age.

- Silhouette scale is an easy and simple to use instrument, helping parents to assess their children's nutritional status.

- Nurses' performance during the child's surveillance appointments may play a fundamental role in the parents' awareness and in the resulting adoption of healthy lifestyles.

REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- How can nurses help parents become aware of their children's true nutritional status?

- Can parents' recognition of their children's true nutritional status imply changes in eating habits and physical activity?

- Is the child's age an influencing factor in the parental perception of their silhouette?