Asthma is a common chronic respiratory disease and a major cause of morbidity and mortality (Ozoh et al, 2019a). Approximately 300 million people have been reported to have asthma worldwide and this number is predicted to increase to 400 million by 2025 (Dharmage et al, 2020). The Sub-Saharan countries are not spared the health burden of asthma, with increased prevalence and exacerbation of symptoms among different age groups (Adeloye et al, 2013; Kwizera et al, 2019). In Nigeria, the prevalence of asthma is inconsistent and the nationally representative information needed for health intervention is not available (Ozoh et al, 2019b). However, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Musa and Aliyu (2014) revealed that the prevalence of asthma among people aged 13 years to 65 years ranged from 5.12% to 14.7% and the overall pooled estimate was 10.2%. The results of a recently conducted nationwide study indicated that the ‘prevalence (95% confidence interval) of physician diagnosed asthma, clinical asthma and wheeze is 2.5% (2.3–2.7%), 6.4% (6.0–6.64%) and 9.0% (8.6–9.4%) respectively’ and this value increased with age (Ozoh et al, 2019b). Even with the inconsistent data in Nigeria on the prevalence of asthma, a rising trend can be seen in the prevalence of asthma among adolescents.

Asthma among school children has been a source of concern for stakeholders because the condition has been linked to increased school absence leading to poor academic performances (Desalu et al, 2019), more emergency room visits, stigma and psychological trauma for both adolescents and parents (Kaplna and Price, 2020; Bakula et al, 2019; Licari et al, 2019)

Important goals of childhood asthma management are to ensure good symptom control, to avoid the limitation of physical activities by the disease, to ensure good partnerships between health-care providers and patients/caregivers and to give comprehensive asthma education. These goals are only achievable if health-care providers have good knowledge of the disease, particularly the socio-demographic factors, triggers, comorbid conditions and clinical profile, as well as local perception of childhood asthma, medication use, and drug availability in the particular locality (Isik and Isik, 2017).

‘Important goals of childhood asthma management are to ensure good symptom control, to avoid the limitation of physical activities by the disease, to ensure good partnerships between health-care providers and patients/caregivers and to give comprehensive asthma education.’

Özdemir and Sürücü (2019) and Desalu et al (2019) documented that poorly controlled asthma is a major contributor to school absence among adolescents, eventually affecting school performance. Besides absence, Shams et al (2018) observed that adolescents with poorer control of asthma often have psychological comorbidities. Other effects of poorly controlled asthma on adolescents include poor sleep quality, reduced socialisation (Isik and Isik, 2017), burden on the caregivers and overall reduced quality of life (Bose et al, 2018; Kosse et al, 2019). Appropriate management of asthma in schools has a significant impact on asthma control among adolescents. According to Langton et al (2020), ensuring asthma is well-controlled helps adolescents to learn better and participate fully in school activities. Adolescents spend the greater part of their time in school under the care of their teachers, making teachers one of the first lines of help should an adolescent have an attack during school hours. Limited or no access to a school nurse further places the teachers at the forefront and means they carry an increased burden of responsibility of care for adolescents with asthma (Cain and Reznik, 2016). The US National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (2007) made the case that schools, teachers, communities, parents, school nurses, school physicians and other major stakeholders can work with adolescents with asthma to help them to perform at their best.

The Asthma Friendly School Initiative (AFSI) dictates a partnership between health institutions, educational institutions, and the wider community for managing school children and adolescents living with asthma within the school environment (American Lung Association, 2020). According to the American Lung Association (2020), school personnel, families, community organisations and health-care providers all have a role in making schools ‘asthma friendly’. According to Datt et al (2019)—considering the case study of Islington in London, UK—schools need to be asthma friendly to be able to achieve maximum asthma control. The researchers further suggested that building partnership between education and health is key to ensuring the physical and emotional wellbeing of adolescents with asthma. As corroborated by Vu (2019), school nurses have important roles to play in the co-ordination of care, communication and education of students and all school staff with the overall aim of preventing school absence.

However, in Nigeria, there is no initiative directed at asthma-friendly schools, although a component of the National School Health Policy (Federal Ministry of Education, Nigeria, 2006) addresses the adequacy of school environment, though with no emphasis on asthma-friendly schools. The few studies carried out were on teachers' knowledge of asthma and the availability of facilities for asthma care in public schools (Kuti et al, 2017; Adeyeye et al, 2018). There is dearth of information on the knowledge of teachers regarding the characteristics of an ‘asthma-friendly’ school model, perception of their role in the control of asthma and their opinion on the existence of a partnership between the school and the parents of adolescents with asthma in the control of asthma, which this study was designed to describe.

Research question

What factors will predict teachers' perception of their roles in the control of asthma among adolescents?

Methods

Participants

This study adopted a descriptive cross-sectional design and was carried out in eight privately owned secondary schools in Osun State, Nigeria. The schools were selected purposively by identifying secondary school adolescents who had asthma and were receiving care at nearby hospitals to the schools. The adolescents were then traced to their schools and the schools were selected for the study. A total sample size of 388 high school teachers participated in the study. The teachers were selected from each of the schools using proportionate sampling technique.

Instruments

A structured, self-administered questionnaire was used to collect data. The questionnaire was adapted from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program guidelines. The guidelines were restructured to produce questions that could assess the teachers' knowledge of asthma-friendly schools, their role perceptions and school–parent partnership. The questionnaire was in four (4) sections. Section A contained nine (9) questions that elicited information on the socio-demographic variables of the teachers. Section B: contained twenty (20) items with Yes or No responses that assessed knowledge of asthma-friendly schools while Section C contained 15 Likert scale questions of 5 options (Strongly disagree to Strongly agree) that assessed the perceived roles of teachers in the control of asthma. Lastly, Section D contained six (6) items that assessed teachers' opinions on the partnership between the school and parents of adolescents with asthma in the control of the disease. The partnership questions had two response options of ‘No partnership’ and ‘Partnership in place’. Test-retest reliability of the instrument was carried out with a resultant correlation coefficient value of 0.83 among teachers in another secondary school with characteristics similar to the selected schools for the study.

Procedure

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethical review board of the Institute of Public Health of Obafemi Awolowo University College of Health Sciences (HREC Number: IPH/OAU/12/498). Approval for the study was also received from all the schools involved. The selected teachers were given information about the study in the staff rooms of each of the schools during the lunch break. Clarifications about the study were addressed and the investigator obtained informed consent of the teachers. The questionnaires were then administered to the teachers. Some filled in and returned the questionnaires immediately while some returned the filled questionnaires the following day. A total of 380 teachers returned completely filled questionnaires giving a response rate of 98%.

Data analysis

Data collected were analysed using SPSS Statistics version 23 (IBM Corp 2015). The knowledge questions with response options of Yes (1) and No (0) had a total obtainable score of 20. The scores were converted to percentages and scores of less than 50% were categorised as ‘poor’ knowledge, 50–59% as ‘fair, while 60% and above were categorised as ‘good’ knowledge. The perceived roles section, which was measured on a 5-point Likert scale of ‘Strongly agree’ (5) to ‘Strongly disagree’ (1), had a total obtainable score of 75. The mean score of 49.0 was used as a threshold to dichotomise the scale into ‘poor perception’ (≥ 49.0) and ‘good perception (<49.0). Teachers' opinion of partnership with response options of partnership (1) and no partnership (0) had a total obtainable score of 6. Linear logistic regression analysis was carried out to determine the predictors of perception of the teachers in relation to their socio-demographic variables and knowledge. The level of significance for the test statistics was taken to be P≤0.05

Results

The age of the teachers ranged from 21 years to 66 years with the mean age of 36.50 ± 7.34 years. There were more females (56%) than males (45%) in the study. Over half (61%) of the teachers had between 1 and 10 years' experience in teaching job with mean experience of 9.65 ± 7.10 years. Other characteristics of the teachers are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of teachers

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 20–29 | 67 | 17.6 |

| 30–39 | 187 | 49.2 | |

| 40–49 | 112 | 29.5 | |

| ≥50 | 14 | 3.7 | |

| Mean ± SD | 36.50 ± 7.34 | ||

| Gender | Male | 169 | 44.5 |

| Female | 211 | 55.5 | |

| Religion | Christianity | 335 | 88.2 |

| Islam | 42 | 11.1 | |

| Traditional | 3 | 0.8 | |

| Marital status | Single | 123 | 32.4 |

| Married | 252 | 66.3 | |

| Separated | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Divorced | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Widowed | 3 | 0.8 | |

| Highest education level attained | *SSCE | 3 | 0.8 |

| ∞NCE/OND | 31 | 8.2 | |

| BSc/BA/BEd/** HND | 298 | 78.4 | |

| MSc/MA/MEd | 45 | 11.8 | |

| PhD | 3 | 0.8 | |

| Subject taught in school | Science | 213 | 56.1 |

| Arts | 126 | 33.2 | |

| Commercial | 41 | 10.8 | |

| Years of experience as a teacher | <5 | 108 | 28.4 |

| 5–10 | 124 | 32.6 | |

| 11–15 | 83 | 21.8 | |

| >15 | 65 | 17.1 | |

| Mean ± SD | 9.55±7.10 | ||

| Years of experience in the current school | <5 | 192 | 50.5 |

| 5-10 | 143 | 37.6 | |

| 11-15 | 37 | 9.7 | |

| >15 | 8 | 2.1 | |

| Mean ± SD | 5.41±4.26 | ||

NCE/OND = National Certificate of Education/Ordinary National Diploma

**HND = Higher National Diploma

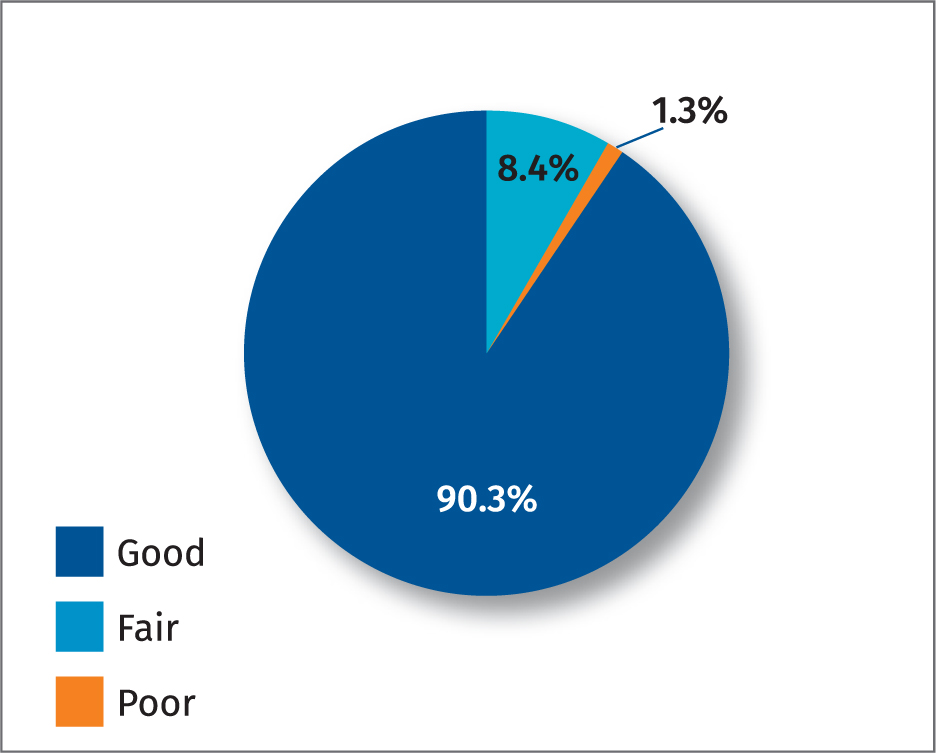

Many (94.5%) of the teachers knew that school should have a policy or rule that allows students to carry and use their own asthma medicine; followed by knowledge that the school and grounds should be free of tobacco at all times (93.9%), and adolescents with asthma should have quick and easy access to medicine if they do not carry their own asthma medicine (Table 2). A summary of the teachers' knowledge of the asthma-friendly school model showed that the majority (90.3%) of them had good knowledge, some (8.4%) had fair knowledge while the rest (1.3%) had poor knowledge as seen in Figure 1.

Table 2. Knowledge of teachers on the asthma-friendly school model

| Items | Yes n (%) | No n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| The school building and ground should be free of tobacco at all times | 357 (93.9) | 23 (6.1) |

| Schools should have a policy or rule that allows students to carry and use their own asthma medicine | 359 (94.5) | 21 (5.5) |

| Adolescents with asthma should have quick and easy access to medicine if they do not carry their own asthma medicine | 347 (91.3) | 33 (8.7) |

| Schools should have a written emergency plan for teachers and other staff to follow to take care of a student who has an asthma attack | 308 (81.1) | 72 (18.9) |

| In an emergency, such as fire a outbreak or if a student forgets their medicine, schools should have standing orders and an inhaler for adolescents to use | 328 (86.3) | 52 (13.7) |

| Students who have asthma should have updated action plans on their file in the school | 343 (90.3) | 37 (9.7) |

| The school nurse or other staff should be able to assess, and monitor students who have asthma in your school | 326 (85.8) | 54 (14.2) |

| The school nurse should help students with their medicines and helps them to participate fully in exercises and other physical activity including physical education, sports, etc. | 307 (80.8) | 73 (19.2) |

| The school nurse should readily and routinely be available to write and review plans and give the school guidance on asthma control | 318 (83.7) | 62 (16.3) |

| An asthma education expert should teach all school staff about asthma, asthma action plans and asthma medicines | 332 (87.4) | 48 (12.6) |

| Asthma information should be incorporated into health class, or first aid class and other classes as appropriate for the students | 319 (83.9) | 61 (16.1) |

| Students who have exercise-induced asthma should be free to choose another exercise without the fear of being ridiculed or receiving reduced grades in subjects like physical education | 307 (80.8) | 73 (19.2) |

| School partners with parents and school nurse to address students' asthma needs | 303 (79.7) | 77 (20.3) |

| The schools with nurse need not work with asthma specialists in the community | 291 (76.6) | 89 (23.4) |

| The school helps reducing or preventing student contact with allergen or irritants that can make their asthma worse | 274 (72.1) | 106 (27.9) |

| Excessive dust is present in the school | 71 (18.7) | 309 (81.3) |

| Cockroach droppings are present in the school | 63 (16.6) | 317 (83.4) |

| Pets with fur or hair are present in the school | 68 (17.9) | 312 (82.1) |

| Strong odors or sprays are present in the school | 85 (22.4) | 295 (77.6) |

| Mold or persistent moisture is present in the school | 88 (23.2) | 292 (76.8) |

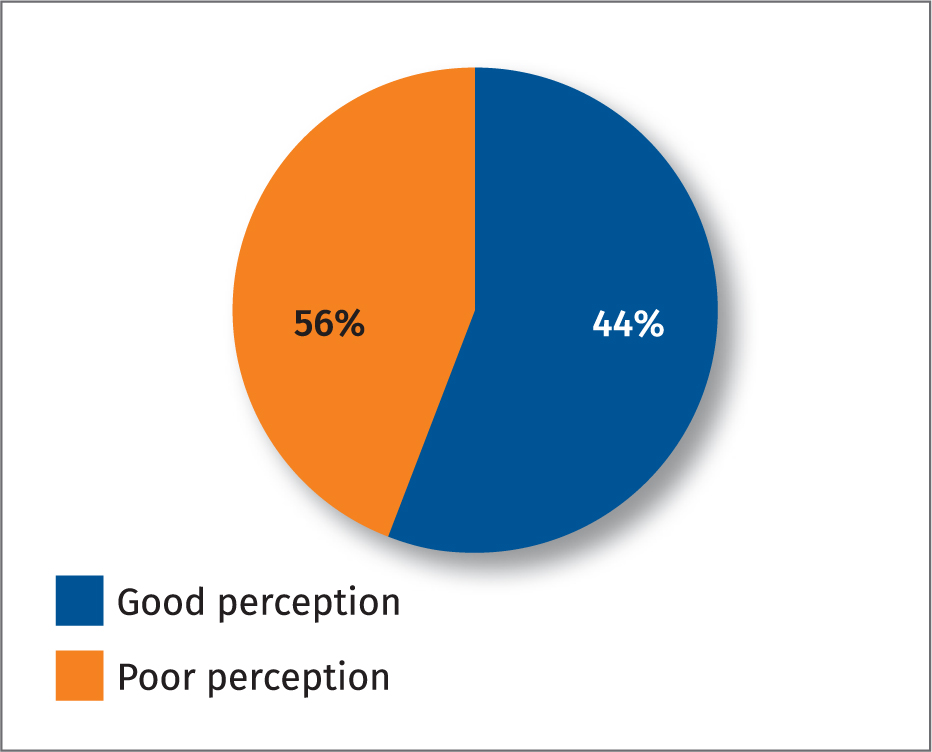

Analysing the responses of the teachers to each of the role perception items (Table 3) showed that over 50% of the teachers agreed and strongly agreed to many of the statements as their roles in the control of asthma. However, the statement ‘Know the signs and symptoms and the early warning signs of asthma episode’ was poorly agreed to as 27% strongly disagreed, 31% disagreed, while 14% were not sure. A summary of the teachers' perception of their roles in the control of asthma showed that 44% had poor perception while 56% had good perception (Figure 2).

Table 3. Teachers' Perception of their roles in the control of asthma

| Items | Strongly disagree n (%) | Disagree n (%) | Not sure n (%) | Agree n (%) | Strongly agree n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Be in possession of a written action plan for each adolescents with asthma | 58 (15.3) | 42 (11.1) | 37 (9.7) | 91 (23.9) | 152 (40.0) |

| Know how to easily assess a student's asthma action plan | 20 (5.3) | 45 (11.8) | 42 (11.1) | 127 (33.4) | 146 (38.4) |

| Review action plan with the students and parents to determine if classroom modifications are necessary | 25 (6.6) | 18 (4.7) | 65 (17.1) | 139 (36.6) | 133 (35.0) |

| Develop a clear procedure with the student and parent for handling school work missed | 13 (3.4) | 19 (5.0) | 43 (11.3) | 160 (42.1) | 145 (38.2) |

| Report if a student's symptoms are interfering with learning or activities with peers | 12 (3.2) | 16 (4.2) | 32 (8.3) | 145 (38.2) | 175 (46.1) |

| Alert school management, school nurse or parents of changes in student's performance or behavior that might reflect trouble with asthma | 15 (3.9) | 16 (4.2) | 29 (7.6) | 142 (37.5) | 178 (46.8) |

| Advise the school nurse when you suspect poorly controlled asthma in an adolescent | 35 (9.2) | 68 (17.9) | 43 (11.3) | 117 (30.8) | 117 (30.8) |

| Be able to identify adolescents with asthma, and observe the things that make asthma worse or better in the adolescents | 21 (5.5) | 35 (9.2) | 59 (15.6) | 144 (37.9) | 121 (31.8) |

| Understand triggers and symptoms for adolescents with asthma | 30 (7.9) | 46 (12.1) | 64 (16.8) | 125 (32.9) | 115 (30.3) |

| Know the signs and symptoms and the early warning signs of asthma episode | 102 (26.8) | 117 (30.8) | 53 (13.9) | 59 (15.6) | 49 (12.9) |

| Reduce allergies and irritants in the classroom | 41 (10.8) | 50 (13.2) | 40 (10.5) | 110 (28.9) | 139 (36.6) |

| Plan school activities in a way that ensures adolescents with asthma can fully participate | 41 (10.8) | 73 (19.2) | 40 (10.5) | 90 (23.7) | 136 (35.8) |

| Be alert for signs of uncontrolled asthma | 27 (7.2) | 43 (11.3) | 32 (8.4) | 111 (29.2) | 167 (43.9) |

| Never delay getting medical help for an adolescents with severe/persistent breathing difficulty | 17 (4.5) | 33 (8.7) | 33 (8.7) | 101 (26.5) | 196 (51.6) |

| Consult with school nurse or principal to update policy and procedures for asthma control | 40 (10.5) | 51 (13.4) | 34 (8.9) | 103 (27.2) | 152 (40.0) |

The findings from this study showed marital status as a major predictor of perception of the teachers (OR=4.57, CI=1.66–12.60, P=0.003) (Table 4). This means that married teachers are 4.6 times more likely than unmarried teachers to perceive themselves as having a role to play in the control of asthma among adolescents. In the context of this study, the married teachers include the married or previously married.

Table 4. Predictors of teachers' perception of their roles in the control of asthma among adolescents

| B | Adjusted OR (95% C.I) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 20–29RC | - | - | - |

| 30–39 | -0.75 | 0.47 (0.12 – 1.87) | 0.285 | |

| 40–49 | -0.02 | 1.02 (0.49 – 2.12) | 0.957 | |

| ≥50 | -0.43 | 0.65 (0.12 – 3.62) | 0.623 | |

| Gender | MaleRC | - | - | - |

| Female | 0.02 | 1.02 (0.49 – 2.12) | 0.957 | |

| Religion | ChristianityRC | - | - | - |

| Others (Islam, Traditional) | -0.28 | 0.75 (0.27 – 2.08) | 0.584 | |

| Marital status | SingleRC | - | - | - |

| Married | 1.52 | 4.57 (1.66 – 12.60) | 0.003 | |

| Highest Education | Below first degree (SSCE/NCE/OND) RC | - | - | - |

| First degree (BSc/BA/BEd/HND) | -0.41 | 0.66 (0.18 – 2.47) | 0.541 | |

| Postgraduate (MSc/MA/MEd/PhD) | -1.33 | 0.26 (0.06 – 1.27) | 0.096 | |

| Subject taught in school | ScienceRC | - | - | - |

| Arts | -0.27 | 0.77 (0.35 – 1.66) | 0.498 | |

| Commercial | -0.13 | 0.88 (0.27 – 2.91) | 0.837 | |

| Years of experience | <5RC | - | - | - |

| 5–10 | -0.21 | 0.81 (0.30 – 2.21) | 0.680 | |

| 11–15 | -0.43 | 0.65 (0.12 – 3.62) | 0.623 | |

| >15 | -0.18 | 0.83 (0.11 – 6.10) | 0.857 | |

| Years of experience in the current school | <5 RC | - | - | - |

| 5–9 | 0.23 | 1.26 (0.44 – 3.55) | 0.667 | |

| ≥10 | 1.55 | 4.71 (0.83 – 26.65) | 0.080 |

RC: Reference category

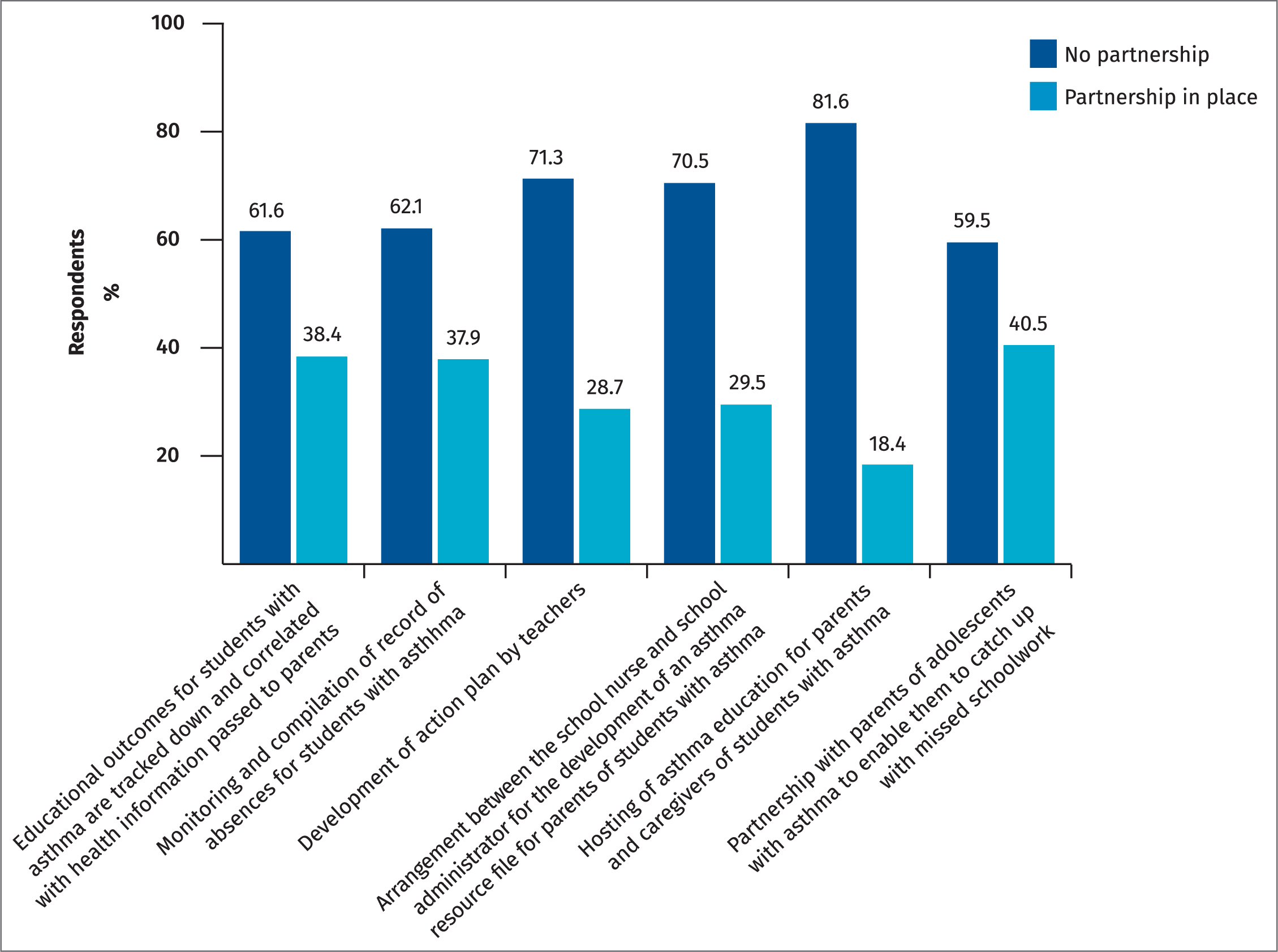

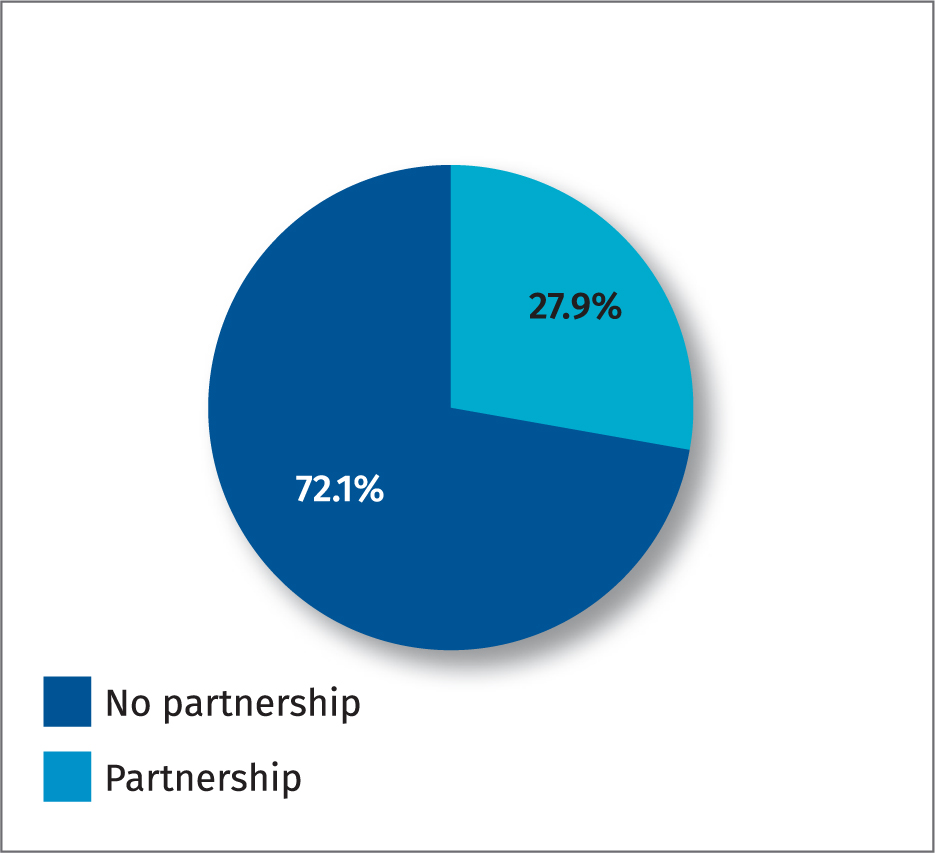

The questions on school–parent partnership showed that there was low partnership between the two parties. According to the teachers' responses, less than half (41%) of the teachers reported that the school partnered with the parents of adolescents with asthma to ensure that the students catch up with school work missed due to asthma episodes. The activity where there was the least partnership was the school hosting asthma education for parents and caregivers of adolescents with asthma (18%). Cumulatively, 28% of the teachers reported there was partnership between the school and parents of adolescents with asthma while 72% reported there was no partnership.

Discussion

Teachers are well positioned to help adolescents control their asthma, improve the health of school-going adolescents and reduce absence from school. Many studies have previously been conducted to assess the knowledge of teachers on childhood asthma. However, little has been mentioned on their knowledge regarding the asthma-friendly schools model. This may be due to the fact that it is a new concept that is yet to be established in Nigeria. Making the school building free of tobacco at all times and not exposing pupils to smoke and dust is essential to have control over asthma, as recognised by the teachers in this study. This was also supported by Adeyeye et al (2018) in a study carried out in Lagos, in the south-west of Nigeria. The use of asthma action plan allows for optimal control of asthma and improved health outcomes (Hynes et al, 2019). Findings from this study reveal that the majority of the teachers agreed that an individualised action plan that is regularly updated in collaboration with the school nurse should be made easily accessible in the classrooms of adolescents with asthma. According to Arekapudi et al (2020), an action plan on asthma is needed to facilitate role recognition in the control of asthma.

The proportion of teachers who had good perception of their roles in the control of asthma increased with age, years of experience and the number of years spent in the current school. It varied depending on the marital status, gender and by the subject being taught.

As documented by McClelland et al (2019), the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute has structured guidelines recommended for classroom teachers in the management and control of asthma. The roles include: being able to alert the school management, school nurse or parents of changes in performance that might reflect trouble with asthma, being alert for signs of uncontrolled asthma, and planning school activities in a way that ensures adolescents with asthma can fully participate. In the current study, using the mean score as a threshold to dichotomise the scale into poor or good perception, just over half (56%) of the teachers had a good perception of their role in the control of asthma. Although the school health programme is the basic structure on the ground in Nigeria to promote the health of school-going adolescents, emphasis can be laid on the teachers being familiar with their roles in the control of asthma. This is in line with the argument made by Jaramillo and Reznik (2015) in a systematic review on adherence to the US National Guidelines on asthma management in the classroom.

The asthma-friendly school model entails a collaborative synergy between the stakeholders. The stakeholders include adolescents with asthma, teachers, school nurses, physician, games masters/physical education (PE) teachers, school administrators and the community as a whole. More emphasis is placed on the role of the parents/guardian when these adolescents are not in school but at home. Although all actions are directed towards the goal of improving asthma control while adolescents are at school, a partnership between the parents of adolescents with asthma and the school teacher is essential to best meet the school's own needs and circumstances.

A strong partnership between the parent and school of adolescents with asthma has been shown to enhance asthma control. As opined by Kakumanu and Lemanske (2019), it establishes a circle of support to facilitate control of asthma. The support of the school and active involvement of parents offer unique opportunities for adequate planning and care for adolescents with asthma.

The school nurse is the coordinator of all these collaborative efforts, and school health services managed by licensed school nurses are the most effective way in which schools can meet the needs of adolescents with asthma for safe, continuous and coordinated care in a safe physical environment. Most of the things that ought to promote partnership between the school and the parents of adolescents with asthma are not in place. In the teachers' opinion, the level of partnership is below average, in terms of helping the adolescent with asthma to catch up with missed classes, hosting of asthma education for parents, arrangements for the development of an asthma resource file for parents, and for creating a platform for the adolescents' physician to be involved in the development of an action plan for them. There have not been systematic efforts to find out the educational outcomes for adolescents with asthma as opined by the teachers. Having control over asthma involves a coordinated effort between the school and parents of adolescents with asthma. However, findings from this study show that health information related to asthma is not being passed across to parents as well as other activities that can foster good partnership between the school and the parents of adolescents with asthma.

Limitations

The study is limited by its scope in terms of the components of the ‘asthma-friendly school’ explored. Also, the study was conducted in South-West Nigeria, hence the findings cannot be generalised to schools in the entire country.

Conclusions

The chances for better asthma-friendly schools lie in the hands of the major stakeholders in the school community (school administrators, teachers, other members of staff, the student population, the school nurse, adolescents with asthma and their parents). Good knowledge among teachers and the better perception of their roles in the control of asthma will go a long way to ensuring an asthma-friendly environment for school-going adolescents with asthma. Although schools serve different needs for varying individuals, complications relating to asthma will be minimised among in-school adolescents with asthma when their asthma is controlled.

It is recommended that further studies be carried out in public schools because the majority of secondary schools in Nigeria are public ones managed by the government. Although the teachers had good knowledge on asthma-friendly schools, an Asthma Friendly School Initiative could be introduced as a separate entity in the Nigerian Education System. While awaiting the introduction of Asthma Friendly Initiatives in Nigeria, the National School Health Policy should incorporate basic components of asthma-friendly schools in the school health services. Improving knowledge will positively influence their perceived roles in the control of asthma—achieving the overall aim of preventing school absence, optimal academic performance, sound physical and emotional wellbeing.

Implications for school nurses

Despite the increasing demand for school nurses, most schools are without nurses in Nigeria. Coupled with the fact that there is an increased prevalence of asthma among adolescents, it is imperative that the limited school nurses available will assist in putting necessary measures in place to promote asthma control. As seen in developed countries, certified asthma educators can be trained on current guidelines to follow on asthma care and on making schools asthma friendly. Furthermore, as a major stakeholder in the care of adolescents with asthma, teachers can alert nurses when exacerbation of symptoms is observed and even be trained on what to do in an emergency situation.