Analysis of the school nursing service's response to youth violence and serious youth violence in two London boroughs was undertaken following raising incidents of youth violence in the area.

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2002) defines violence as ‘the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment or deprivation”.

Definitions of youth violence vary, especially when stipulating the age bracket that constitutes ‘youth’. The WHO (2002) include children and young people aged 10–29 years old, whereas the Metropolitan Police Authority (2012) use 1–19 years old in their definition. However, organisations are in agreement that serious youth violence is an offence of the most serious violent or weapon-enabled crime, which include murder, manslaughter, rape, wounding with intent and causing grievous bodily harm. Youth violence includes lesser offences, such as assault with injury and acts of bullying (WHO, 2002; Metropolitan Police Authority, 2012; London Safeguarding Children Board, 2017).

Youth violence is acknowledged as an international concern. Worldwide, among those aged 10–29 years old, homicide is the fourth leading cause of death, with 200 000 homicides occurring each year; this is 43% of the total number of homicides globally (WHO, 2015). In England and Wales, during the year ending March 2019, of the 58 900 proven offences committed by children and young people (aged 10–17 years old), the main offence type was ‘violence against the person’, which accounted for 30% of all proven offences (Ministry of Justice, 2020). Also, there were around 4500 knife or offensive weapon offences committed by children and young people resulting in a caution or sentence. The majority (97%) were possession offences and the remaining 3% were threatening with a knife or offensive weapon offences (Ministry of Justice, 2020). Statistics from the two London boroughs include:

- A total of 4000 youth violence offences were committed between April 2017 and March 2018, 20% of which were serious youth violence offences (Borough 1)

- The highest levels of knife crime (781 offences) and knife crime with injury (255) offences in London (Borough 1)

- The number of police-recorded victims of serious youth violence increased by 71% between 2012 and 2018 (Borough 2)

- Between 2013 and 2017, there was a 13% increase in hospital admissions involving a sharp instrument or knife injury for those aged under 25 years old (Borough 2).

Exposure to youth violence has been shown to impact both physical and mental health (David-Ferdon and Simon, 2014). Children and young people exposed to violence have increased risk of enuresis, sleeping problems, loss of appetite, low self-esteem, depression and suicidal ideation (Klomek et al, 2007; Gini and Pozzoli, 2009). As a consequence, this exposure can interfere with children and young people's ability to study and achieve their potential (Schwartz and Gorman, 2003). Exposure to youth violence can lead to children and young people to engage in risk taking behaviours, such as substance misuse, delinquency and sexual promiscuity, which in turn causes a financial burden on society (Luk et al, 2012; David-Ferdon and Simon, 2014). The cost of violence to the NHS is equivalent to other major health issues such as alcohol use and smoking (Bellis et al, 2012). Therefore, youth violence is identified as posing a significant public health risk.

Youth violence has traditionally been managed through the criminal justice system, intended as a deterrent (Neville et al, 2015). However, currently in the UK there is a drive for a public health approach to tackling youth violence (Home Office, 2018; Public Health England [PHE], 2019a). The public health approach to serious youth violence aims to reduce violence by identifying and tackling underlying risk factors that make children and young people more likely to perpetrate violence (WHO, 2020). An example of the public health approach being used has been demonstrated by the Scottish Violence Reduction Unit. The unit was founded in 2005 after Scotland was branded the most violent country in the developed world (Violence Reduction Unit, 2020). Since the unit's introduction, Scotland has seen homicides fall to their lowest level since 1976, with a 39% decrease over the last decade (Scottish Government, 2019). The unit takes a multi-disciplinary approach involving serving police officers, civilian police staff, health, education, social work and other fields, which is key to a public health approach (Hagell, 2019). Plastow et al (2019) believes school nurses are in a unique position to contribute to the public health approach in reducing youth violence. However, the evidence for the impact school nurse interventions have is minimal.

The rise in violent crimes nationally and internationally has resulted in the implementation of violence prevention programmes across the world (O'Connor and Waddel, 2015). These programmes focus on either primary prevention, aiming to avoid involvement in youth violence, or use targeted interventions, aiming to lessen harm and reduce risk to those already involved in youth violence (O'Connor and Waddel, 2015). A systematic search of the literature identified 11 studies that all used an experimental design to measure effectiveness of a violence reduction intervention. These 11 studies evaluated nine violence reduction programmes (Table 1).

Table 1. Violence reduction programmes

| Programme title | Key characteristics |

|---|---|

| The INTEMO programme (Castillo et al, 2013) | Based on emotional intelligence the programme aims to improve student's understanding and regulation of emotions. The programme lasted two years and each academic year the student's received 12 taught one-hour sessions, delivered in the classroom. |

| Respect in Schools Everywhere (RISE) (Connolly et al, 2015) | Mental health workers recruited and trained 25 high school students to be peer leaders. They were trained with the skills and knowledge to manage peer aggression and lead peer aggression workshops. Students received two classroom presentations led by youth leaders. |

| Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS) (Crean and Johnson, 2013) | Described as a Social and Character Development programme, it aimed to reduce violence by strengthening skills in emotional literacy, positive peer relations and social problem solving. PATHS consists of lessons, pictures, photographs and posters designed to be delivered by teachers. There is flexibility in how the lessons are delivered across the school years. |

| The Fourth R (Crooks et al, 2015) | Programme takes a Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) approach to promote healthy relationships and target peer violence. Using role-play, students are given opportunities to practice ways to resolve conflicts. Lessons were delivered by usual classroom teachers who received a one-day training course. |

| Growing Against Gangs and Violence (GAGV) (Densley et al, 2017) | Aims to cultivate resilience against gangs and antisocial groups, promote healthy relationships, expose the myths around gangs and share the realities. Lessons are delivered by facilitators alongside the police (or other relevant community partners) and they focus on the consequences of knife crime, drug crime and peer on peer on violence. |

| Gang Resistance Education and Training (GREAT) (Esbensen et al, 2013) | Consists of lessons delivered predominantly by law enforcement officers. The main goals are: to avoid gang membership, reduce violence and criminal activity and help YP develop positive relationships with law enforcement. Teaches students about crime, its effects on victims, conflict resolution skills and life skills training. |

| Second Step: Student Success Through Prevention (SS-SSTP) (Espelage et al, 2013; Sullivan et al, 2015; 2017) | Lessons address interpersonal conflicts and problem solving, empathy and perspective taking, anger management diffusing a fight, dealing with bullying and resisting gang pressure. Delivered by either teachers or facilitators. |

| Count on Me (Jimenez-Barbero et al, 2013) | Brief intervention sessions, focussed on group discussion. Aims to develop empathy, self-esteem, social skills and capacity to solve conflicts in order to modify attitudes towards violence. |

| Violence Prevention Project (Thompkins et al, 2014) | Programme uses skill building exercises to improve student's conflict related attitudes and behaviours. The programme is made up of units: Self-concept, Group Dynamics, Vision and Imagination and Conflict Management. |

When looking at the effect the interventions had on physical violence, two studies noted a reduction in physical violence in the intervention group, compared to the control (Castillo et al, 2013; Espelage et al, 2013). Castillo et al (2013) and Espelage et al (2013) found a statistically significant effect on physical aggression with the INTEMO and SS-SSTP programmes, compared to the control group post intervention. However, during implementation of the INTEMO programme, 15.75% of the sample were lost, as a result of students changing classes or leaving the school (Castillo et al, 2013). Drop-outs can potentially bias the results because students who display aggressive behaviours are more likely to be excluded from schools and educated in alternative provisions (Graham et al, 2019). Therefore, the effect of the INTEMO programme may have been exaggerated because of drop-out of more aggressive students.

Mixed results were found in two studies (Crean and Johnson, 2013; Crooks et al, 2015). The intervention group in the ‘Fourth R’ programme (Crooks et al, 2015) self-reported higher knowledge of violence, awareness of the impact of violence and better coping strategies than the control. However, the study did not record any pre-intervention data. Therefore, it is not clear if the effects seen in the intervention group were as a result of the intervention alone or another variable. The ‘PATHS’ programme (Crean and Johnson, 2013) showed no significant effect on self-reported aggression or reported victimisation overtime, however, teachers delivering the PATHS programme did report a reduction in aggression over the 3 years. However, teaching staff were not blinded to the intervention, which could have biased the behaviour they reported.

The other seven studies did not find the violence intervention programme to have any statistically significant effect on physical aggression and violence. The youth-led RISE programme (Connolly et al, 2015) measured outcomes through completion of self-report questionnaires. Results showed the programme was effective in changing attitudes towards violence but had no impact on reported victimisation by students. However, self-report measures of aggression may not be a reliable measure. Thompkins et al (2014), who implemented the ‘Violence Prevention Project’, found all study participants (intervention and control) showed an increase in antisocial conflict resolution skills, over the 4 years of the programme's implementation. Overall, the effectiveness of violence reduction interventions reviewed in this literature was found to be limited.

Methods

Aims

- To better understand the current school nurse role in relation to youth violence

- Examine interventions currently delivered by the school nursing team, specifically to reduce youth violence.

Objectives

- Explore what universal prevention methods and what targeted interventions are delivered by school nurse staff, focusing on youth violence

- Ascertain staff views and experiences on how they think youth violence education should be provided to children and young people

- Explore staff understanding of the public health approach to youth violence and discuss how the school nursing service utilises this approach

- Audit referrals received from emergency department, where youth violence concerns have been identified, to ascertain if the referral process was followed.

Data collection

An online, self-completion, survey (Box 1) was administered to school nurse staff after piloting the survey with two staff members. An audit was conducted of referrals to the school nursing service, from the emergency department, where concerns around youth violence had been noted (Table 2).

BOX 1.SURVEY QUESTIONS

- Do you understand what the ‘Public Health Approach’ to serious youth violence is? Yes/No/Unsure Please provide an explanation of what you think the ‘Public Health Approach’ to serious youth violence is.

- What do you feel the school nursing team's role is in relation to youth violence?

- In relation to school nursing, what experiences do you have working with children or young people that have been either victim or perpetrator of youth violence? If none, then please state none.

- Have you referred to, or made contact with, any of the following agencies for support when working with children or young people who have been involved in youth violence? Please select ‘None’ if applicable (list provided). Please provide details of your contact.

- On a scale from 0 to 5, how confident do you feel in identifying a young person who may be involved in gangs? Please provide some examples of how you would make this identification.

- Have you ever delivered a classroom lesson or assembly on youth violence? If yes, please provide details. Yes/No/Please provide details.

- Do you feel that school nursing has a role in educating children and young people about youth violence? If yes, how do you see this education being delivered? Yes/No/Please provide details

- On a scale from 0 to 5, 5 being most confident, how confident would you be in delivering education to children and young people on youth violence? This may be in a 1:1 situation or in a group teaching session.

- Do you feel you require further information about youth violence? If yes, what information do you feel you would need? Yes/No/Please provide details

Table 2. Audit tool with data

| Audit question | Yes | No | Not applicable |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emergency department referral has been uploaded by administrator | 60 | 2 | |

| 2. Practitioner reports that consent has been gained for the school nurse referral by emergency department staff? If consent was not reported, clear rationale has been provided | 38 | 24 | |

| Out of the 60 referrals that were uploaded, the following audit question was applied: | 21 | 39 | |

| 3. School nurse has recorded the referral from emergency department within 10 working days (2 weeks) | |||

| Out of the 39 that were not followed up in timescale: | |||

| SN acknowledged referral within 20 working days (4 weeks) | 14 | ||

| SN acknowledged referral within 30 working days (6 weeks) | 6 | ||

| SN acknowledged referral within 40 working days (8 weeks) | 2 | ||

| SN acknowledged referral after 3 months | 1 | ||

| SN has not acknowledged referral – <3 months after referral date | 13 | ||

| SN has not acknowledged referral – >3 months after referral date | 4 | ||

| 44 referrals had been acknowledged by the SN and the following audit questions applied: | |||

| 4. SN records having reviewed any services the child/YP is currently accessing | 30 | 14 | |

| 5. SN records having attempted contact with parent/carer/child or YP to establish that they are accessing appropriate services | 25 | 19 | |

| 6. SN records having seen the child or YP for a face-to-face contact | 9 | 35 | |

| 7. SN records having provided child or YP with health promotion e.g. around sleep, diet, exercise, substances and sexual health | 4 | 40 | |

| 8. SN records having signposted the parent/carer/child/YP to services to support behaviour change. This advice may or may not have been accepted | 8 | 36 | |

| 9. SN records having provided parent/carer/child/YP details of Chat Health or Parentline | 10 | 34 | |

| 10. SN records having signposted YP to SN drop-in | 8 | 32 | 4-primary school aged |

| 11. SN records having made an onward referral to a relevant service, on behalf of client | 2 | 42 | |

| 12. SN records having liaised with school or any other relevant professional e.g. social worker | 30 | 14 | |

| 13. SN records having gained consent to liaise with other professionals or gave a rationale as to why consent was not gained | 7 | 23 | 14-did not liase |

| 14. SN documented a plan of care in the child/YP's notes | 43 | 1 | |

| 15. If SN had planned to follow up with another contact, this contact was reported to be completed | 3 | 18 | 23-no planned follow up |

Sample

Community staff nurses, school nurses and school nurse students, across the two boroughs' school nursing teams, were asked to complete the survey. In total, 41 members of qualified nursing staff were eligible to complete the online survey (excluding the pilot participants).

Data analysis

The audit process provided quantitative data, while the staff survey provided a mixture of quantitative and qualitative data. The quantitative data collected were analysed using descriptive statistics. Qualitative data were analysed using themes.

Consent and confidentiality

Consent was gained from the NHS Trust and had met the ethical requirements set by the Trust in relation to confidentiality and use of patient data. Anonymity was maintained throughout. Consent for participation in the survey was implied when staff submitted their responses. Participants were advised that responses would be anonymous and no identifiable information would be included in the final report.

Results

Staff survey findings

The survey was completed by 15 staff, giving a response rate of 36.6%.

Overall, 27% of staff stated that they understood a public health approach to serious youth violence. Staff provided a variety of explanations, with four themes reported. Table 3 provides examples of respondent quotes related to the themes. One participant stated they felt the public health approach involved health promotion and discussing the effects of serious youth violence on child health. However, this was not reported in any other responses. Another participant stated the public health approach involves ‘identifying and evaluating current practices', but this was also not discussed by other participants.

Table 3. Staff understanding of the public health approach to serious youth violence

| Theme | Staff responses |

|---|---|

| Finding ways to prevent serious youth violence | ‘…putting systems in place which will prevent serious youth violence.’‘…ways to prevent serious youth violence.’‘to steer young people away from knife crime and violence.’ |

| To explore causes of serious youth violence in communities | ‘…Looking at public health factors, including poverty, deprivation, social integration, conduct and emotional disorders and the prevalence of serious youth violence within different communities/areas in the borough.’‘…Looking at the wider picture i.e. causes that have led young people to be involved in serious youth violence/family dynamics/community/school/future opportunities/home situation…’ |

| Taking a multi-agency approach and collaborative working | ‘A collaborative approach including a [multidisciplinary team] in supporting the wider community to distribute promotion…’‘…A multi-agency working approach to reducing incidences of violent crime…’ |

| Using national guidelines and policies | ‘…national and targeted campaigns’‘…Ensuring that governments take responsibility and put in place the correct policy, legislation and guidance for all organisations to address serious youth violence.’ |

Multi-agency working and being able to signpost children to other services was reported frequently by participants as the role of the school nurse in serious youth violence. Participants' most frequently reported utilised service was social care. Table 4 summarises the responses. Health promotion and identifying health needs amongst children and young people involved in youth violence was acknowledged by staff to be an important part of the school nurse role. Delivering specific youth violence education was not mentioned by any participant, but offering general health promotion around promoting safety and healthy relationships was discussed.

Table 4. Staff responses regarding the school nurse role in serious youth violence

| Theme | Staff responses |

|---|---|

| Signposting children and young people to other services | Five participants used the phrase ‘signposting’ to other services for further support, when a need has been identified. |

| Prevention of serious youth violence | ‘Promote prevention of violence in schools.’‘…preventative education/promotion re: personal and community safety, healthy relationships, exploitation…’ |

| Identification of vulnerable children and young people and safeguarding | ‘…to identify vulnerable children, young people and families on our caseloads that may need extra support or interventions for serious youth violence prevention.’‘…ensure we are all safeguarding these young people effectively.’ |

| Multi-agency working and sharing concerns across agencies | ‘To continue to work with the professional network to ensure we are all safeguarding’‘Liaising with social/youth offending service workers and schools if necessary.’‘Following up with schools i.e if a child has attended A&E (as sometimes schools are unaware)’ |

| Working with those involved in youth violence and identifying health needs | ‘Following up and supporting children and young people who are involved.’‘…identifying health needs of those already involved in youth violence’‘…Follow up with the young person to discuss wound care, antibiotic cover, emotional wellbeing…’ |

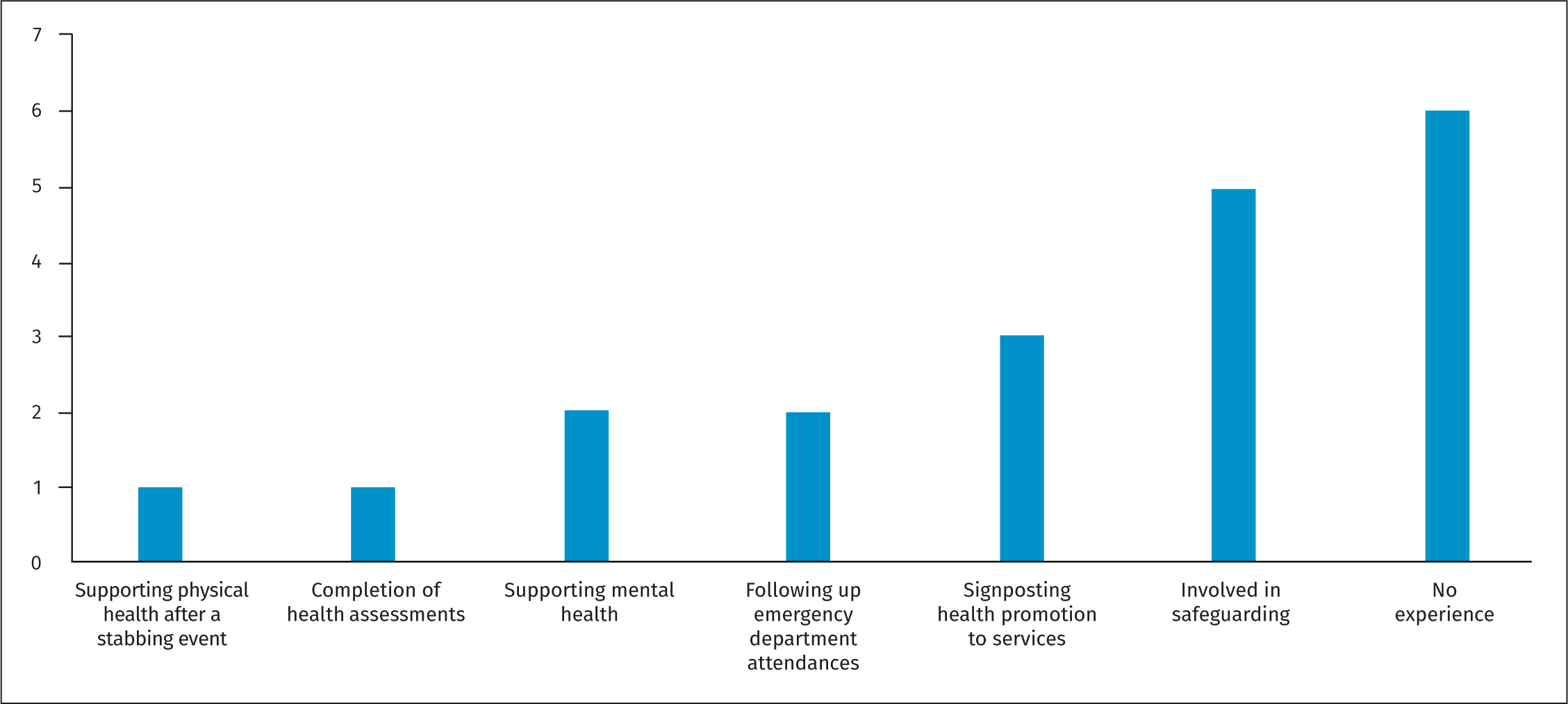

Figure 1 summarises the responses regarding participants reported experience of working with children and young people in relation to serious youth violence, with ‘no experience’ being the most common response. Involvement in safeguarding processes was the most common experience reported by staff. No staff reported experience of delivering universal primary prevention, all experiences were reported to be targeted interventions, where youth violence had already been identified.

Figure 1. Number of school nurse experiences with serious youth violence

Figure 1. Number of school nurse experiences with serious youth violence

Staff confidence and knowledge was assessed by asking: ‘On a scale from 0 to 5, how confident do you feel in identifying a young person who may be involved in gangs?’ The average rating for staff confidence was 2.53. The most common confidence score reported by participants was 3. Two participants reported difficulty in identifying those involved in gangs, as they are guarded about sharing information. Observable changes in children and young people's behaviour, appearance and school attendance were most frequently reported by participants (Table 5).

Table 5. Participant responses on how to identify gang involvement in children

| Theme | Staff responses |

|---|---|

| Physical possessions and monetary gains, inconsistent with the child's age and family background | ‘You are aware of the young person's family's financial circumstances, and the young person have expensive clothing/items on them. Unable to explain how they have purchased them.’‘…openly have access to more cash that would be normal for their age (even bring it in to school sometimes!)’ |

| Episodes of missing from home and/or education | ‘…disappear for unaccountable reasons overnight/for long periods.’‘Missing from home or education…frequently changing home/education provision’ |

| Changes in mood, personality and behaviour | ‘changes in behaviour (becoming more negative)…self-neglect’‘Assessing the child's emotional (and physical) wellbeing’‘…change in behaviour…poor emotional state’ |

| Associating with gang members or risky individuals or having knowledge about gangs | ‘…changes in peer groups…’‘They talk about known gangs, “aren't in them” but know people, young person feeling unsafe in certain areas of the boroughs.’‘Asking about friends-are they the same age or older… Area they live in-associated to gangs’ |

| Being involved in criminal activity | ‘…more than 1 mobile phone, being arrested more - especially if out of the local area’‘Carrying a weapon, being coerced or carrying “things” for other people, having a tag name, curfew times … carrying a burner phone, involved in incidents’ |

| Being involved in risk taking behaviours | ‘…risk taking behaviour…at risk of STIs pregnancy, child sexual exploitation, sexually harmful behaviours…’‘frequent emergency department attendances’ |

| Poor parenting and lack of parental support | ‘…looking out for vulnerabilities-issues at home/child protection/child in need, parental issues-Toxic trio…’‘…living in a home with poor boundaries/homeless…parents with mental health difficulties, domestic violence or substance misuse. Children and young people with poor attachment and lacking caring adults or bereavement.’ |

| Past experiences that increase a child's vulnerability to grooming | ‘Looked after child, child with learning needs or vulnerable child due to history of bullying…’ |

| Being guarded about the information that is shared | ‘this can sometimes be very difficult as young people are evasive and very good at hiding information as this could be normality for them for many years.’‘I think young people who may be involved in gangs are very cautious in the information they share making it difficult when you are working with opinions and third party information rather than facts.’ |

No participant reported delivering universal education on youth violence in their role as a school nurse or community staff nurse. However, 13 (86.67%) respondents stated they felt the school nurse had a role in educating children on youth violence but acknowledged that this is not being delivered currently. Staff reported serious youth violence education should be delivered in collaboration with others and some participants felt they would be unable to educate children and young people on youth violence because of a lack of staff training and information. The average score for confidence in delivering a teaching session on youth violence to children and young people was 2.2. All participants felt they required further information on serious youth violence (Box 2).

BOX 2.FURTHER INFORMATION REQUESTED BY PARTICIPANTS

- Updates on relevant legislation e.g., Modern Day Slavery Act and National Referral Mechanism

- Training on how to identify children and young people at risk of youth violence

- Information on organisations to signpost children and young people to for further support

- Discussion points and questions to ask children and young people you are worried about in order to engage in conversation

- Information on the school nurse role/local strategy in supporting children and young people involved in serious youth violence or youth violence

- Information on how to support schools and provide education in schools

- What health promotion to give children and young people to keep themselves safe and avoid gangs

- Information from partner agencies specialising in youth violence

- How to support emotional health and deal with trauma

- What the process should be for following up children who have attended the emergency department because of youth violence

- A list of resources and interventions that can be used with children and young people

Audit of emergency department referrals

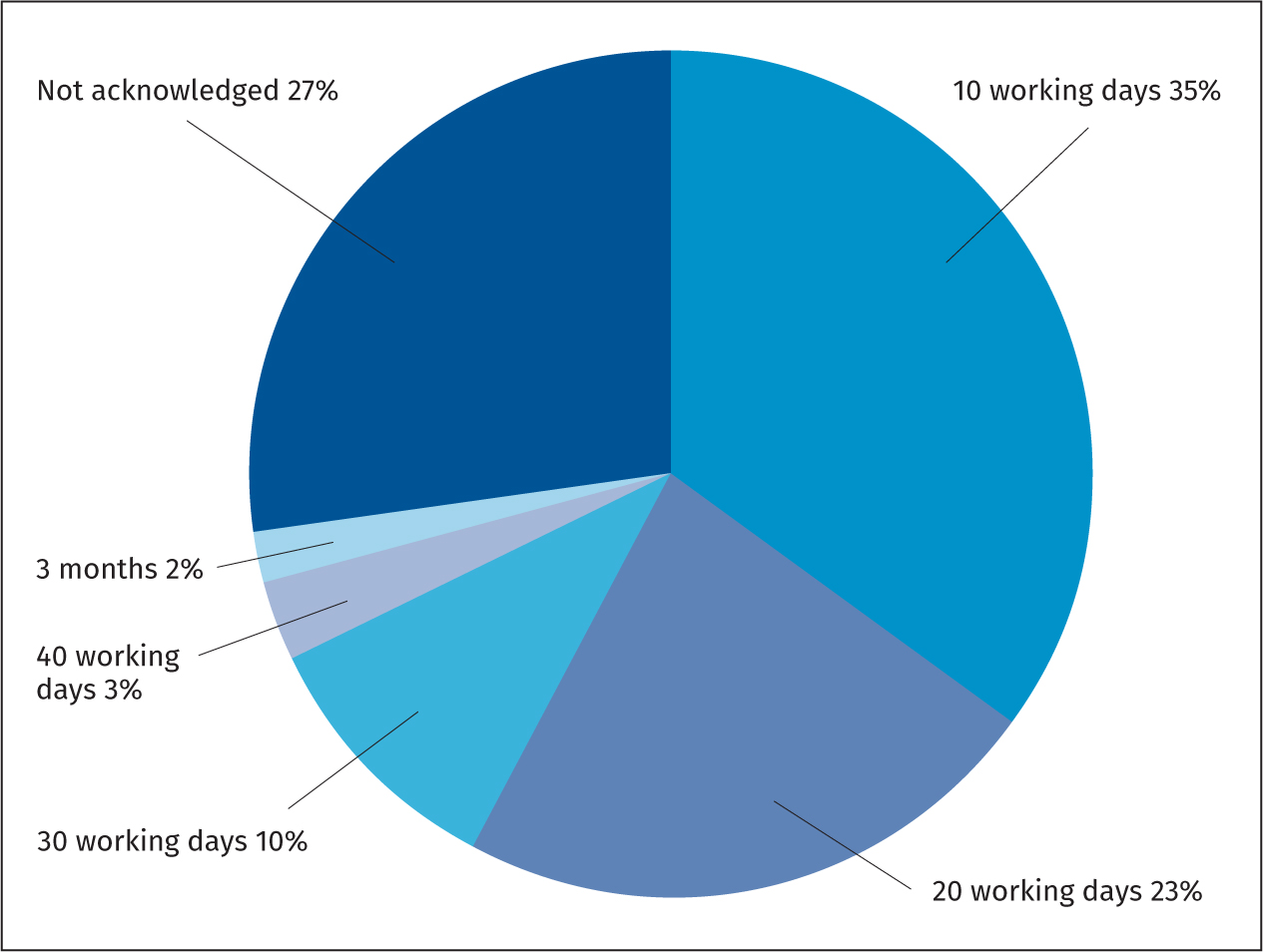

In total, 62 emergency department referrals fitted the inclusion criteria and were selected for audit (Table 2). Two referrals had not been appropriately uploaded to the child's records leaving 60 referrals for analysis, 21 referrals were acknowledged within the 10 working days required within the local emergency department referral protocol. Figure 2 shows the amount of time staff took to acknowledge referrals.

Figure 2. Time taken for staff to acknowledge emergency department referral on client's records

Figure 2. Time taken for staff to acknowledge emergency department referral on client's records

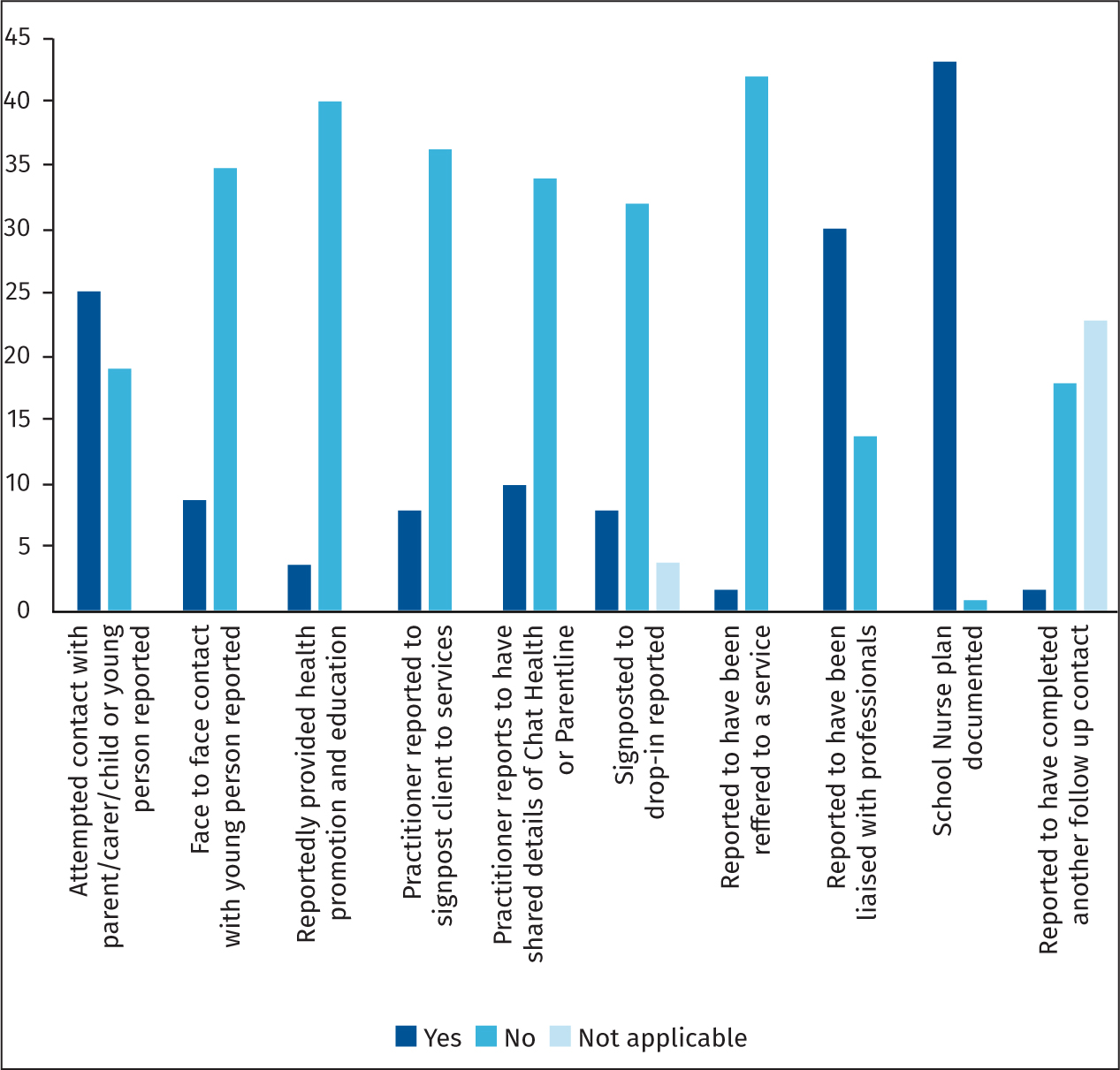

At the time of the audit, 16 referrals (27%) had not been acknowledged. The 44 acknowledged referrals were reviewed against the audit questions. Figure 3 provides a summary of results, detailing the documented actions by staff. Only 9 (20.5%) referrals were followed up with a face-to-face contact with the referred client and 9% (44 referrals) were documented to have been followed up by providing some level of health promotion. More practitioners reported sharing details of the school nurse drop-in (18%) and 22.7% reported providing details of Chat Health or Parentline.

Figure 3. Summary of results regarding follow up provided

Figure 3. Summary of results regarding follow up provided

A plan of care was documented on all records except one. A further follow-up contact or intervention was documented in the school nurse plan for 21 of the referrals. However, at time of audit, only three of these clients were reportedly seen again, meaning 18 clients had reportedly not been followed up as planned.

Discussion

Primary prevention is at the core of public health and the school nursing service, with school nurses having expertise in preventative health care (Royal College of Nursing, 2020). The ‘Healthy Child Programme 5–19 years' (Department of Health and Social Care, 2009) focuses on prevention, promotion and early intervention (Department of Health and Social Care, 2014) and is utilised by school nurses to guide the service. The Healthy Child Programme does not explicitly discuss youth violence, but does highlight the school nurse role in providing a safe and happy learning environment for children and young people, free from bullying. When reviewing the survey findings, there were no universal primary prevention methods reported by staff, explicitly youth violence focused. Participants were asked what they understood the school nurse role to be in relation to youth violence and only three participants (20%) discussed universal prevention to be a school nurse responsibility in this area. All other responses identified the school nurse role to involve targeted interventions for example, signposting vulnerable children and young people to specialist services for support.

Participants in the survey did acknowledge the use of health promotion as a primary prevention method, which could indirectly impact youth violence. For example, school nurses deliver education on healthy relationships and sexual consent, which can reduce the risk of violent behaviours (Plastow et al, 2019). School nurses also provide education to children and young people on substance misuse, which could indirectly impact youth violence as a link has been demonstrated between alcohol use and assault rates (van der Merwe and Dawes, 2007), with the assumption that alcohol and drug use dis-inhibits the user, impacting their actions. Finally, school nurses provide education to children and young people on maintaining good mental health. Psychological conditions can cause children and young people difficulties in concentration that can lead to problems in school performance and attendance, which increases the risk of violence (Office of the Surgeon General (US) et al, 2001). This study did not collect data on the wider health promotion activities undertaken by school nurses in the local area. However, health promotion being delivered by school nurses could indirectly impact youth violence. Nevertheless, it would not be possible to measure the impact this advice has locally because of other external variables. For example, health promotion offered by school nurses usually covers a varied selection of topics and it would be impossible to isolate the contribution of a single element of health promotion to any observed change.

Survey participants reported they had never delivered an education session on youth violence and their confidence level in delivering a teaching session was reported to be 2.2 out of 5, which could be interpreted as low. Staff also reported they required further resources and training to be able to deliver youth violence education to children and young people. The majority of staff (86.67%) felt school nurses had a role in youth violence education and suggested this be delivered jointly with partner agencies, such as police and the voluntary sector. Such a collaborative approach would be appropriate, as violence is the result of several risk factors and there is no single solution. Therefore, a whole system approach where professionals have a shared goal is advocated (Home Office, 2018).

The staff survey asked what experiences staff had working with children and young people involved in youth violence. Examples of direct work being undertaken included supporting physical health after a stabbing event, completing health assessments and supporting mental health. These were clear examples of targeted interventions provided by school nurses. However, there were no examples of universal primary prevention work. The most common service utilised was social care, supporting the finding that school nurses provide targeted support for identified vulnerable children and young people more frequently than they undertake primary prevention. A qualitative study exploring the role of the school nurse in health promotion and PSHE found similar themes, whereby targeted interventions were more commonly delivered because school nurses had large child protection caseloads (Hoekstra et al, 2016).

Participants reported they would like further guidance on a number of different topics, including how to recognise children and young people involved in serious youth violence and how to engage them in conversations. However, there is no local guidance on how to support children and young people involved in youth violence or any suggestions for staff on how to engage identified children and young people in conversations. Furthermore, staff have not received training in how to support the emotional wellbeing of those involved in a significant trauma, such as a stabbing or shooting, which was highlighted in the staff survey. This perhaps explains why ‘signposting to other services' was consistently reported in the survey, as participants may feel inexperienced, or under resourced, to offer direct support on the topic and more comfortable to signpost other services.

The audit showed 68% of referrals were followed up with liaison to either the child's social worker, school safeguarding lead or another professional. However, only 20% of referral follow ups provided a face-to-face contact with the referred client. What is apparent from the audit of emergency department referrals is staff were more likely to concentrate on the safeguarding aspects of the referral (ie information sharing with professionals), rather than see the referral as an opportunity to provide an appropriate intervention. This is not necessarily a surprising result, given safeguarding is an integral part of the school nurse role and is seen as a priority. In two qualitative studies (Hoekstra et al, 2016; Littler, 2019), school nurses reported safeguarding would often take priority over health promotion and another study acknowledged the time child protection record keeping takes can impede a school nurses ability to be present in school (Harding et al, 2019). Safeguarding the welfare of children is not solely the responsibility of the school nurse, and multiple professionals are often involved in cases where child protection concerns have been identified. Therefore, when safeguarding concerns have been highlighted, the school nurse should liaise with the wider professional network, ascertain what each professional's role is, and what interventions will provide the most value. However, this should not be at the expense of direct contact with the young person.

Of the nine face-to-face contacts with children and young people, four reported providing health promotion, for example education on healthy relationships, sexual health or substance use. When an emergency department referral is received where youth violence has been identified, school nurses should prioritise health promotion education, as potentially no other professional will be able to offer this. Providing this vulnerable group with health promotion advice is crucial, as children and young people involved in gang violence are more likely to have poorer health outcomes, for example drug and alcohol use, unsafe sex with multiple partners, mental health problems, be victim to violent crime, suffer from cancer in adulthood, have high blood pressure and die prematurely (Sanders et al, 2009; Frisby-Osman and Wood, 2020; Rima et al, 2020). There are many examples from practice where school nurse-led targeted interventions have been successful in reducing alcohol consumption, smoking and teenage pregnancies (Turner and Mackay, 2015). Research shows risk of violent behaviours can be reduced through health education (Plastow et al, 2019); however, this group are less likely to access healthcare or have access to healthcare promotion advice, with the majority seeking help from the emergency department in moments of crisis (Sanders et al, 2009).

This study has highlighted a gap in the school nursing service, which is the lack of universal primary prevention and education being delivered directly focusing on youth violence. There is also a lack of education being delivered at the secondary level of prevention, focusing on youth violence, which was evidenced through the audit. Throughout the study, it was apparent staff require a better understanding of their role in relation to youth violence. In England, there is currently no guidance explicitly discussing the school nurse role in relation to youth violence prevention. The Home Office (2013) provides guidance to schools and teachers on developing an approach to tackle youth violence, but the school nurse role is not discussed. However, in the USA, the National Association of School Nurses (2018) have released a position statement on the role of the school nurse in reducing violence, and provide online violence prevention resources for school nurses. This lack of clarity regarding the position of the school nurse in the UK was reported by participants to be a barrier to providing education on serious youth violence, and participants requested further information regarding the school nurse role and the local strategy.

The findings from this study must be interpreted with caution, because of the limitations of the study, such as the low response rate, which could mean that results may not represent the views and experiences of the boroughs' school nurses. The data available were also limited and may not reflect the universal health promotion that indirectly targets youth violence. However, this study has highlighted an important but currently neglected aspect of school nurse practice, where there is very limited information.

Conclusions

In conclusion, school nurses are recognised as being leaders in the delivery of health promotion to those from 5–19 years old and play a key role in public health. However, the school nurse service has minimal evidence of any universal primary prevention being delivered focusing on youth violence and the audit highlighted there was a lack of health promotion being delivered at the secondary level of prevention. Staff currently report low confidence in delivering universal education to children and young people on youth violence and therefore need further support and guidance to include this in their role. Staff should be encouraged to have discussions with schools and partner agencies to see how school nurses can work collaboratively in delivering key messages to children and young people on youth violence. Children and young people involved in youth violence are at higher risk of poor health outcomes and also less likely to access health promotion advice. Therefore, the school nurse needs to recognise they have an important role in reducing health inequalities in children and young people exposed to youth violence.