The safeguarding of a child's wellbeing is a fundamental part of the role of the school nurse (Department for Education [DfE], 2018). This article explores the subject of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in relation to safeguarding drawing upon relevant evidence, theory, and policy. The role of the school nurse as a specialist community public health nurse (SCPHN) within the safeguarding arena will be discussed with reference to collaborative and multi-agency work. The legal, policy and professional frameworks underpinning safeguarding and public health practice will be critically considered. While reference is made within this article to safeguarding within the NHS context, safeguarding is applicable within all health and social care organisations and contexts.

Methods

A literature search was carried out using academic databases (CINAHL complete database, Medline and Google Scholar). The following key words (school nurse, adverse childhood experiences, resilience, safeguarding children, collaborative working, public health, communities) were used. Inclusion criteria included being published between 1998 and 2021, in the English language, academic articles and government documents (including guidelines), generalisability and transferability. Articles with a narrow focus, particularly with a social work background, were excluded as they were lacking in transferability.

Literature review

Policy background

According to the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund, every child has the right to live in a safe environment and be protected from abuse, including violence and neglect (UNICEF, 1989). The safeguarding of a child's wellbeing is a fundamental part of the role of the school nurse (DfE, 2018). It could be argued that the Children Act (1989) provides the cornerstone of the safeguarding legislation used in the UK (Owen, 2009). However, initially it was not without a conservative credo which did not allow for the demonstration of a true child-centred approach (Owen, 2009). Subsequent amendments and government documents, for example the Adoption and Children Act (2002) have gone some way to address this issue. For example, the recognition of unmarried fathers as having parental responsibility is significant, since it puts the child's needs at the centre of policy (Owen, 2009). The concept of safeguarding children has seen further extensive development over the past few years, due largely to recommendations made following serious case reviews and reports (Reid, 2017). Significantly, reports by Lord Laming (2009) and the Munro Review (2011) helped strengthen the legal framework for safeguarding children and resulted in crucial developments such as the introduction of local safeguarding children boards. The current statutory guidance Working Together to Safeguard Children (DfE, 2018) provides the core legal requirements for organisations such as the NHS. Keeping the child at the centre of care decisions is an essential part of the role of professionals, including the school nurse, when working collaboratively with parents, carers, and other agencies (DfE, 2018). The document clarifies when and how information should be shared in order to safeguard children.

What are adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)?

ACEs refer to traumatic experiences that occur in the lives of young people before the age of eighteen, which may have long-term negative effects on physical and emotional health (WAVE Trust, 2021). Felitti et al (1998) identified ten distinct ACEs which fall under the umbrella terms of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction (Table 1).

Table 1. The 10 original ACEs

|

It is argued that ACEs are being commonly used as important indicators of poor health outcomes (McLennan et al, 2020). It is suggested that the cumulative effect of ACEs has an impact on the ‘Neurological, immunological, and hormonal development of children … increasing the risk of accelerated development of chronic disease and early death’ (Bellis et al, 2018).

There is ample evidence to demonstrate the connection between adversity in childhood and an increased risk of youth psychopathology (McLaughlin, 2016), as well as physical difficulties (McLaughlin and Sheridan, 2016). McLaughlin and Sheridan (2016) argue that to develop an understanding of why ACEs have such a profound impact on developmental processes, it is necessary to consider the construct of adverse experiences. The original ten ACEs, it is indicated, have gone largely unquestioned (McLaughlin and Sheridan, 2016). However, there have been some more recent additions, including poverty (Hughes and Tucker, 2018; Children First, 2018), and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic (Sinha et al, 2020) (Table 2). The long-term effects on children of lockdown, increased poverty, and increased levels of domestic abuse due to the pandemic are as yet unknown (Sinha et al, 2020). However, it is predicted that it will further widen the socio-economic, health and educational gap, increasing the vulnerability of children across the country (Public Health England [PHE], 2020; The Guardian, 2020).

Table 2. Adverse community environments

|

The study of ACEs has provided empirical evidence for the need to end the repeating pattern of exposure to certain early-life experiences which may have negative long-term effects, according to Dube (2020). In the original study, Felitti et al (1998) concluded that ACEs can affect the long-term health and wellbeing of adults. However, by their own admission, there were certain limitations to the interpretation of the results of the original study (Felitti et al, 1998). These included its self-reporting nature, physiological brain function, or attitudes to health that may influence the health status reported by adults in the study (Felitti et al, 1998). Another interesting point being that the study cohort consisted of mostly white adults, who were well educated and had access to good health care (Dube, 2020). Edwards et al (2017) seriously question the validity of the ACEs research and outcomes, casting doubt on factors such as the findings' transferability, the imprecise variables of the ACEs such as the length of time a child is exposed to an ACE, and the risk of pathologising people when the lines between what is considered ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ are indistinct. Finkelhor (2018) also argues that the study captured adversities during a particular era, which may not necessarily be transferable to contemporary society.

Working with vulnerable families

Safeguarding children involves creating a safe environment in which children can grow and develop physically and mentally, free from harm, and where organisations and agencies are proactive in ensuring they can achieve the best outcomes in life (DfE, 2018). Nurses working with children and young people must be equipped with the appropriate knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values needed to provide effective safeguarding practice (Royal College of Nursing [RCN], 2019a). However, it could also be argued that the main responsibility for safeguarding lies with the child's parents or those with parental responsibility (Powell, 2016). Bowlby's (1988) ethological theory of attachment concludes that an infant will naturally form a close relationship with the primary caregiver, and consequently, this relationship will have a lasting social and developmental influence on the child. Positive attachment between the infant and the parent is widely accepted as being fundamental, and indeed critical to the healthy development of the child (PHE, 2019). This is a crucial area of practice where the school nurse can provide vital support to help parents form that positive attachment, which can contribute to building the resilience of the family (Children First, 2018).

The rhetoric surrounding the role of parents and safeguarding can often have negative connotations. Terms such as ‘toxic stress’ may leave some parents feeling they are not good enough and they may struggle to recognise themselves within socially accepted norms of ‘good parenting’ (Valentine et al, 2019). It is worth being mindful of the use of such terms, and noting that parenting is often viewed as one of the most demanding roles anyone will face (Powell, 2016). It is suggested that parents are constantly subject to scrutiny by a range of professionals, whose role it is to escalate any deviation from the currently expected social norm (Valentine et al, 2019). Some studies have indicated, for example, that parents who misuse drugs and/or alcohol, which is identified as an ACE and a risk factor for maltreatment (Stevens, 2019), have also been associated with less consistent and poorer parenting (Hampshire County Council, 2015). Valentine et al (2019) assert, however, that such parents can provide a loving and secure environment for their children with the correct support. Therefore, the school nurse needs to be alert to potential safeguarding risk factors but be sensitive in the approach taken when working closely with vulnerable families to build a therapeutic relationship when supporting them (RCN, 2019a). The school nurse also requires a good level of understanding of the concept of ‘good enough parenting’ but must consider that this term is subjective (Powell, 2016). To minimise subjectiveness and ensure a consistent approach is taken to safeguarding, the school nurse must follow the local NHS trust and evidence-based safeguarding children partnership policies, working collaboratively with members of the wider multi-agency team.

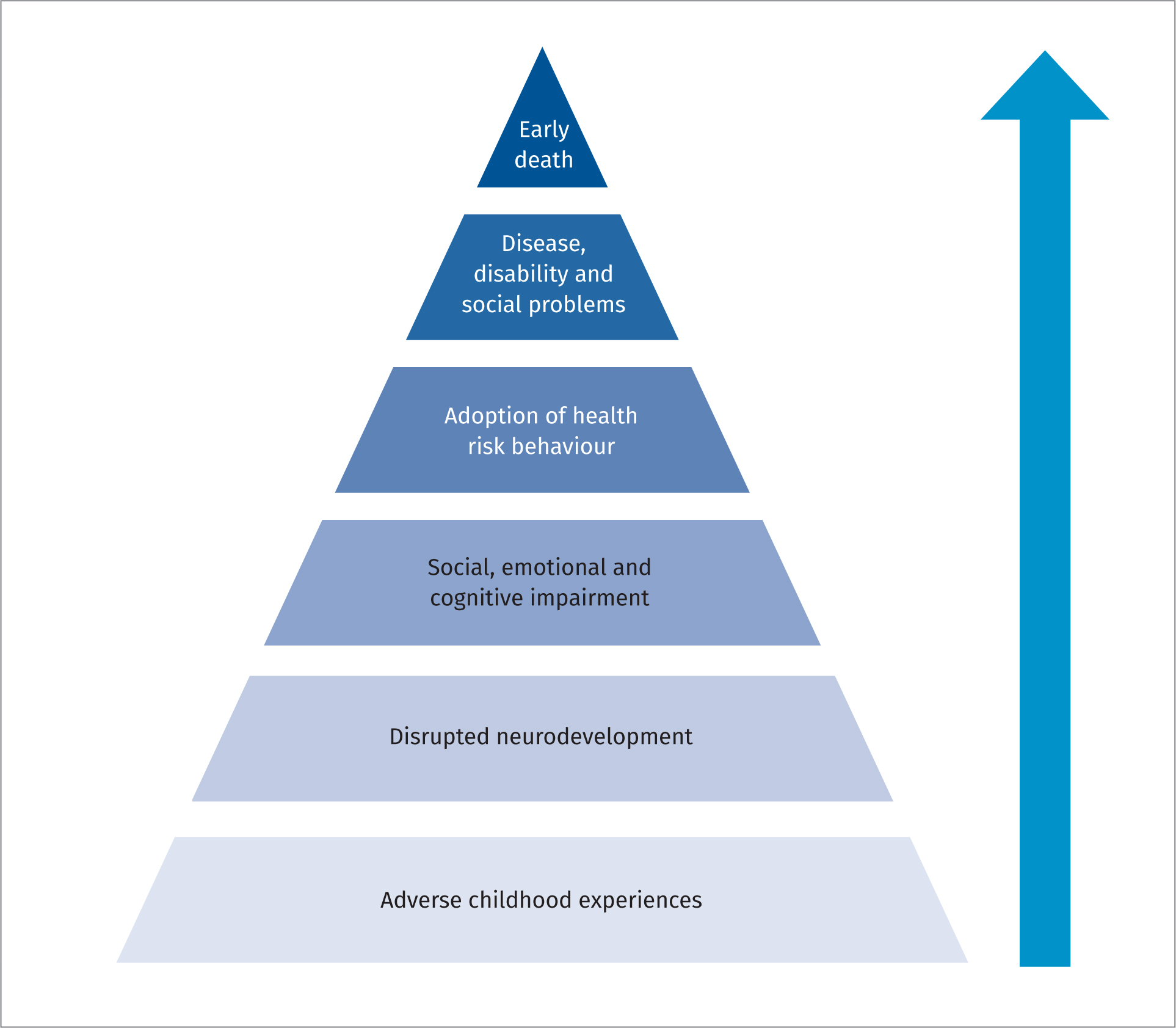

It is believed that when a child is exposed to traumatic or stressful events, cognitive, immune, and nervous system development may be jeopardised, thus having long-term implications on the child's health (World Health Organization, 2021). The consequence of this for an individual child may be devastating (Figure 1).

It may result in a higher susceptibility to disease, mental health problems, poor educational attainment, and a higher number of risk-taking behaviours (Asmussen et al, 2020). Frederick et al (2020) argue that studies have indicated individuals with a higher number of ACEs are disproportionately represented among social care service users. Perhaps unsurprisingly, according to Asmussen et al (2020), of the 399 500 children that were deemed as being ‘In Need’ in England in 2019, 80% had experienced at least one ACE. While there is much evidence regarding ACEs, the development of the brain and how the complex interaction of external factors influence cognitive development, emotional and physical health (NSPCC, 2014), it is important to note that due to the limitations of the evidence base, ACEs should not be used in isolation (PHE, 2020). ACEs must be considered alongside the wider social determinants of health, as there is evidence to suggest that although ACEs are prevalent across society, people living in deprivation are more likely to have experienced them (Asmussen et al, 2020). The implication then being that policies or frameworks that are formulated to address ACEs must also tackle the wider issues of socio-economic deprivation (Asmussen et al, 2020). Asmussen et al (2020) state that unless public health policies address the wider determinants of health, and evidence-based early intervention strategies are integrated into policy, the effectiveness of interventions will be limited. It is suggested that taking a whole-system public health approach can ensure that not only vulnerable children and families receive targeted interventions by skilled professionals, but that wider community issues such as poverty can also be addressed, thus helping to reduce inequalities (Marmot, 2020).

Moving toward a more collaborative approach

Parton and Reid (2017) claim that child protection is a social construct, and as such is ever changing depending on the socio-economic and political climate. It could therefore be proposed that the same applies to safeguarding. Changes to safeguarding legislation, such as the move toward a more collaborative multi-agency approach and the increased recognition of the influence of early years' experience on the long-term health and wellbeing of children reflect the current political and economic environment. Spratt et al (2019) assert that being aware of specific ACEs that can widely be associated with potential undesired outcomes later in life allows health and social care professionals to develop a policy and interventions that can address these issues. While there is evidence of a commitment to addressing ACEs from the Scottish government and in Wales, there is currently no such indication of a similar obligation in England (Stevens, 2019). However, progressive work has been undertaken in some regions and a strong argument developed for the prioritisation of the prevention and mitigation of ACEs within the public health agenda (Stevens, 2019). The importance of a collaborative approach is clear: school nurses do not work in silo and no one professional is able to proactively address ACEs independently.

The public health role of the school nurse

It is postulated that the terminology of ACEs has become largely negative and reductionist (McLaughlin, 2016). This can lead to stereotyping and feelings of shame and guilt among some parents (Valentine et al, 2019). Studies indicate that this could influence parental engagement in support and feelings of self-efficacy when addressing their own parenting and health issues (Valentine et al, 2019). While there is a broad range of literature evidencing the connection between children's wellbeing and factors referred to as ‘adversities’, Devanay et al (2020) point out that it is not inevitable that the ‘adversity’ is traumatic. That is not to say, however, that it is not without consequence, but there are individuals who have experienced ACEs who can continue successfully in life. While it is evident that there is a clear correlation between socio-economic factors and health (Marmot, 2020) this is also not necessarily deterministic (Davidson et al, 2010). Many children who come from disadvantaged backgrounds can thrive (Davidson et al, 2010). This may be linked to the presence of protective factors within the child's life, such as strong support networks for the family which provide resilience (Early Intervention Foundation [EIF], 2018). The school nurse has a vital role to play in helping develop these networks. As a public health professional, the school nurse is skilled in undertaking health needs assessments, identifying community assets, and valuing a co-production approach to addressing local health needs (PHE, 2018b). School nurses can also work with statutory and voluntary sectors to help shape local services that promote resilience (PHE, 2021). The case has been made by some authors that screening for ACEs should be carried out routinely (Kerker et al, 2016). However, Asmussen et al (2020) argue this approach should be considered with caution, due to the lack of robust evidence around the use of screening. The argument for the use of routine screening for ACEs in children and young people to help practitioners offer appropriate client-centred support appears to be lacking in evidence (PHE, 2020). Following their pilot study (REAch), Quigg et al (2018) concluded that along with the ethical issues that would be involved in screening children, there was no clear evidence to show that routine enquiry was of benefit to the client. It was suggested that there may be a risk of re-traumatisation, should ACE questions be asked in an inappropriate manner (Quigg et al, 2018). Indeed, Sneddon et al (2016) conclude that further harm may be done and trust may be eroded if disclosure has been made to one practitioner, then support is offered by another. Blake (2019) argues that to provide a therapeutic relationship, the same school nurse should see the individual child or young person, as the continuity will help build trust. This consistent support could result in better health outcomes for adolescents (Summach, 2011).

Early intervention

Fundamental to the role of the school nurse is that of health promotion and early intervention (Department of Health (DH), 2009). It is well documented that providing effective early intervention is not only beneficial to the health and educational outcomes of children and young people, but is also economically and socially advantageous for the wider society (DH, 2009; Marmot, 2020). Being in the unique position of providing a universal service to children and young people and their families means that the public health nurse is ideally placed to deliver health interventions across age groups (Waterall, 2020). School nurses lead the way in the delivery of the Healthy Child Programme (DH, 2009) and provide the link between children and young people, schools and the community (RCN, 2019b). As such, school nurses are perfectly placed to identify children and young people who are at risk of maltreatment (Harding et al, 2019; RCN, 2019a).

Concepts of childhood

UNICEF (1989) provides an accepted definition of childhood. However, concepts surrounding the ‘child’ and ‘childhood’ do not appear to be universal, and it is suggested that they are heavily influenced by and inexorably connected to cultural and societal differences (Norozi and Moen, 2016). Concepts include seeing the child as physically weaker and less cognitively competent than adults, and the child as being in a state of imperfection in relation to an adult (Norozi and Moen, 2016). Historically, the period of childhood has altered from being a time of working to help support the family, to the post-industrial era where schooling is a legal obligation, and the child is financially dependent on the adult. It is this latter model of childhood which is common in contemporary society today (Norozi and Moen, 2016). James and Prout (2015) offer a useful alternative perspective on what may be construed as this controlling model:

‘That children must be viewed as active participants of society, and their own independent perspectives must be considered…’.

This view is echoed by NICE (2019) and the Office for Standards in Education, Children's Services and Skills (Ofsted, 2011). Following recommendations from the Munro report (2011), children and young people have the right to have their voice heard and recorded accurately (RCN, 2019a). The school nurse should not only listen to what a child or young person has to say verbally, but also be aware that behaviour is a method of communication (Ofsted, 2011). The school nurse needs to be skilled at interpreting what parents or carers have to say and beware of taking things at face value (Ofsted, 2011). Burton and Revell (2018) offer that using higher-level cognitive skills and professional curiosity when working to safeguard children and young people may be challenging for the professional, but transformative in understanding the children and young people's lived experience. School nurses are well placed to use this approach, and to recognise the signs of vulnerable children and young people (PHE, 2018a; RCN, 2019a). The school nurse often works therapeutically with children and young people and families, so may already have built up a level of trust and be able to initiate an appropriate plan of early help (DfE, 2018). School staff are vital sources of information regarding children and young people as they see them daily and can be alert to any changes. However, vulnerable children and young people are not always willing to access support services (PHE, 2018a). Therefore, as leader of the Healthy Child Programme, and with a focus on safeguarding and addressing the High Impact Areas (DH, 2009) the school nurse must work collaboratively with schools and the multi-agency team, following the local safeguarding frameworks to provide safe and effective support to children and young people (PHE, 2021).

Assessment methods

The Common Assessment Framework (CAF) (HM Government, 2006) is often used as a robust method for practitioners to assess the needs of children, young people, and families (Powell, 2013). The CAF can be a useful way of holistically assessing the child, their environment, parenting factors, development, and family situation (H. M. Government, 2015). The RCN (2019a) provides explicit guidance for professionals regarding the appropriate knowledge and skills required when working to safeguard children, which the school nurse must adhere to. Because a substantial part of the school nurse's role is that of safeguarding (RCN, 2019b) it could be suggested that it must be embedded in every contact made (PHE, 2016). The school nurse can help to safeguard children and young people by acting as an advocate and ensuring their voice is heard (RCN, 2019a). An affirmative relationship with the children and young people can be a beneficial and perhaps even protective factor (Maston and Barnes, 2018).

Building resilience

It is believed that the most significant influence on a child's wellbeing comes from his/her carers and immediate circumstances (Frankland, 2017). Some psychology theorists have referred to this as the microsystem in which they live (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2007). This is echoed in current policy, with a strong emphasis on the benefits of a secure and safe relationship existing between the child and caregivers (DfE, 2020). The complex and dynamic concept of resilience has been much debated over the past few decades, in an effort to explain how to promote healthy positive development in children who have been exposed to ACEs (Maston and Barnes, 2018). Resilience can broadly be defined as ‘The capacity … to adapt successfully to challenges that threaten the function, survival, or future development’ (Maston and Barnes, 2018). Maston and Barnes (2018) suggest a significant research finding is that resilience is not restricted to a child's body, but that it is highly influenced by external influences such as the environment and relationships. These could, it is suggested, include ACEs. ‘Preventing or mitigating harm from adverse experiences is one of the most important approaches within a resilience framework’ (Maston and Barnes, 2018).

The school nurse's role in promoting resilience

The school nurse can help support the building of resilience in children and young people and their families through a variety of approaches. The school nurse can help to increase the presence of protective factors, thereby reducing the risk of harm from ACEs, even when risk factors still exist (PHE, 2020). Research indicates that there are three broad strategies required in resilience work with children and young people: risk, asset, and protection focused interventions (Maston and Barnes, 2018) and school nurses are often already skilled in these areas. For example, risk reduction could include ensuring the school nurse is visible and available, educating communities on how to reduce levels of stress, working collaboratively within the multi-agency team and taking the appropriate steps to escalate safeguarding concerns. An asset approach may include work done through a community development project aimed at meeting the local health and wellbeing needs identified through a health needs assessment. Ellis and Dietz (2017) argue that public health, child health, social care and other professionals can work collaboratively with the wider community to build resilience, which in turn results in more resilient children. This reduces ‘toxic stress’ and leads to positive long-term health and wellbeing outcomes (Ellis and Dietz, 2017). Protection strategies may include support around enhancing self-efficacy for children and young people to address certain health issues (Maston and Barnes, 2018). There is strong evidence to suggest that the primary prevention strategy of mindfulness can be useful in helping vulnerable young people reduce the negative effects of stress and trauma-induced symptoms (Sibinga et al, 2016).

The school nurse has the expertise to work collaboratively with others to help communities develop more control over their own health (Buck, 2020) and should use the public health approach of prevention, protection, and promotion (RCN, 2021). Taking an upstream approach (National Health Service (NHS), 2019) and embedding prevention in day-to-day practice is imperative as part of the ‘fifth wave’ of public health (Newland et al, 2021). Moving toward asset-informed rather than trauma-informed care (TIC) may help toward developing a positive relationship with children and young people and families (Galinski, 2020). The evidence for using TIC to help prevent ACEs is not fully understood yet due in part to an absence of empirical evidence on the key components of TIC (Hanson and Lan, 2016). Engaging children and young people and families using motivational interviewing techniques (Miller and Rollnick, 2013) may allow them to be heard and to activate their own resourcefulness in making changes. When used effectively, motivational interviewing techniques can help the individual to feel empowered and safe. They also take a person-centred approach, so vital when safeguarding children and young people.

Discussion

Safeguarding children policy has gained in clarity and focus over recent years. Keeping the child at the centre of all care decisions is imperative, as is a collaborative approach by all health and care agencies involved. ACEs can have long-term negative effects on the health and wellbeing of children and young people, and evidence indicates the wider determinants of health also influence this. The long-term effects of the Covid pandemic are as yet unknown but it has been predicted that the vulnerability of children will increase. Therefore, perhaps now more than ever, the school nurse needs to work closely with individuals and communities to build resilience, emphasise the importance of protective factors such as positive relationships, and support children and young people to thrive.

Conclusions

There is ample evidence demonstrating the potential effects of ACEs on the health and wellbeing of children and young people. However, there is also research to argue that ACEs should not be viewed in isolation, and are not necessarily in themselves deterministic of negative outcomes. With sound knowledge and understanding regarding ACEs, the school nurse can play a vital role as part of the wider team in building the resilience of the community, and provide therapeutic interventions on a family or one-to-one basis with young people, thereby helping to safeguard, support and improve their outcomes.

KEY POINTS

- The safeguarding of a child's wellbeing is fundamental to the role of the school nurse.

- Safeguarding policy provides clear guidelines for professionals working with children, and supports a collaborative approach between professionals to ensure child safety.

- Evidence suggests that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) may have long-term negative impacts on health and wellbeing but may not necessarily be deterministic of trauma.

- As a Specialist Community Public Health Nurse, the school nurse is skilled in undertaking health needs assessments, identifying community assets, and helping to shape services that promote resilience.

- School Nurses can use early intervention strategies, and an asset-based person-centred approach to help vulnerable children and families achieve better health and wellbeing outcomes.

REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- What long-term effects can ACEs potentially have on children, young people and families?

- Why can ACEs often be considered a safeguarding concern?

- What interventions could the school nurse undertake to support children and families?

- What effect might the wider determinants of health have on the prevalence of ACEs within a community?