Healthy childhood development is fostered through sufficient physical activity, limiting sedentary behaviours, and adequate sleep; collectively known as movement behaviours (Moore et al, 2020). Stockwell et al (2021) define physical activity as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscle that results in energy expenditure, and can include exercising, walking, gardening and doing household chores. Sedentary behaviours can be defined as any waking behaviour with an energy expenditure of ≤1.5 metabolic equivalents while in a sitting or reclining posture, including watching TV, video gaming and computer use (Stockwell et al, 2021).

Recent statistics show that in the UK, 9.7% and 20.2% of children aged 4–5 years old and 10–11 years respectively were classed as obese or severely obese in 2018/19, based on data from the National Child Measurement Programme. Compared to 2009/10 data, this represents an overall increasing trend (NHS, 2019), and an escalating problem in the paediatric population. Obese children are at an increased risk of several physical and psychological comorbidities throughout their lifespan, including during childhood where there is an increase in cardiometabolic risk, and chronic illness and premature death later in life (Kumar and Kelly, 2017; Sharma et al, 2019). While the causes of childhood obesity can be multifaceted, one of the main elements that contribute to obesity is the long-term dysregulation of energy balance; an overconsumption of high-energy foods, meaning the child often has too high an energy intake, along with an energy expenditure that is too low, based on spending too much time partaking in sedentary behaviours and not enough physical activity. While the UK government has set a target to cut childhood obesity in half by 2030, worryingly, rates are showing an overall increasing trend.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had far-reaching health, social, and economic implications worldwide (Pietrobelli et al, 2020). Since the start of the pandemic, many countries, including the UK, were put into lockdown, an inevitable method of prevention to limit movement of the public. This meant that the public were banned from participating in unnecessary outdoor activities during COVID-19, encouraging people to stay at home and stay indoors as much as possible. While these lockdowns aimed to limit the spread of COVID-19 and related deaths, there was the potential to impact associated levels of physical activity and sedentary behaviour in the long term (Stockwell et al, 2021). Social restrictions, including remote learning and the closure of activities that children and young people would normally attend, such as dance classes or football sessions, have made it difficult for children and adolescents to engage in physical education, sports, or other forms of school-related or community-based organised physical activity. Additionally, parental limitations because of working from home or loss of childcare may have created challenges in finding ways to keep children physically active (Bates et al, 2020). A number of recent pieces of research have examined the effects that COVID-19 restrictions have had on children globally, in particular in terms of their physical activity and sedentary behaviours.

‘Social restrictions, including remote learning and the closure of activities that children and young people would normally attend, such as dance classes or football sessions, have made it difficult for children and adolescents to engage in physical education, sports, or other forms of…organised physical activity’

COVID-19 and children's physical activity and sedentary behaviour

Dunton et al (2020) carried out research examining the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity and sedentary behaviours in children in the US. They found that, on average, children engaged in approximately 90 minutes of school-related sitting and over 8 hours of leisure-related sitting a day. Parents of older children (ages 9–13 years) vs younger children (ages 5–8 years) perceived greater decreases in physical activity and greater increases in sedentary behaviours from the pre- to early-COVID-19 periods. The authors concluded that short-term changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviours in reaction to COVID-19 may become permanently entrenched, leading to increased risk of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease in children. Given the increasing time since lockdown measures were first introduced, the potential problems routed in sedentary behaviours and low levels of physical activity are likely to be exacerbated.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had far-reaching effects on health, and research shows that lockdown rules have likely resulted in increased sedentary behaviour in children

The COVID-19 pandemic has had far-reaching effects on health, and research shows that lockdown rules have likely resulted in increased sedentary behaviour in children

‘While the UK government has set a target to cut childhood obesity in half by 2030, worryingly, rates are showing an overall increasing trend’

Moore et al (2020) carried out an online survey of Canadian parents (n=1472) of children (5–11 years old) or youth (12–17 years old), just over half of whom (54%) were girls. They assessed immediate changes in child movement and play behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak. Behaviours included physical activity and play, sedentary behaviours, and sleep. They found that only 4.8% (2.8% girls, 6.5% boys) of children and 0.6% (0.8% girls, 0.5% boys) of youth were meeting combined movement behaviour guidelines during COVID-19 restrictions. Children and youth had lower physical activity levels, less outside time, higher sedentary behaviours (including leisure screen time), and more sleep during the outbreak. Parental encouragement and support, parental engagement in physical activity, and family dog ownership were positively associated with healthy movement behaviours. This research demonstrates that family engagement could lessen the negative effects of pandemic restrictions by encouraging more physical activity and less sedentary behaviours within the family unit.

Pietrobelli et al (2020) carried out a study looking at 41 children and adolescents with obesity, participating in a longitudinal observational study in Verona, Italy. Lifestyle information, including diet, activity, and sleep behaviours, was collected at baseline and 3 weeks into Italy's national lockdown. There were no changes in reported fruit and vegetable intake during the lockdown, but they did find that potato chip, red meat, and sugary drink intakes increased significantly. In terms of physical activity and sedentary behaviours, they found that the time participants spent in sports activities decreased significantly, and sleep time and screen time both increased significantly. This dysregulation in energy expenditure could have far-reaching consequences for long-term health in these children.

Xiang et al (2020) conducted a natural experimental longitudinal study among 2427 children and adolescents (6–17 years old) in five schools in Shanghai, China. The first survey was conducted between 3 and 21 January 2020 (the public health emergency began in Shanghai on 24 January 2020) and the second survey between 13 and 23 March 2020 (during the pandemic). They found that overall, the average amount of time spent in physical activity decreased drastically, from 540 minutes per week (before the pandemic) to 105 minutes per week (during the pandemic). They also found that the prevalence of physically inactive students increased significantly, from 21.3% to 65.6%. Screen time considerably increased during the pandemic in total (up by 1730 minutes, or approximately 30 hours per week, on average). This suggests that during the pandemic these children were not meeting the current global physical activity guidelines set by the World Health Organization (2010), which state that children and youth should accumulate at least 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity each day to achieve health benefits.

Between April and June 2020, McCormack et al (2020) surveyed 345 parents of at least one school-aged child (80.5% aged 5–11 years old and 54.9% male) in Calgary, Canada. They found that during this period, most children increased television watching, computing or gaming, and use of screen-based devices. They also found that half of children decreased playing at the park and in public spaces. This increase in sedentary behaviours is likely because there were currently fewer opportunities to partake in physical activity, as a result of a lack of extracurricular sports activities in schools, and the shutdown of organised sports and public sports facilities. These are just a sample of global studies that have recently examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young peoples' physical activity and sedentary behaviours, as well as their dietary intake, but the results are concerning. All of the research points to the fact that the pandemic is having a negative impact on lifestyle, which could have far-reaching consequences.

So what should be done next? Given the numerous physical and psychological benefits of increased physical activity and decreased sedentary behaviour, public health strategies should include the creation and implementation of interventions that promote safe physical activity and reduce sedentary behaviour, should other lockdowns occur (Stockwell et al, 2021).

‘Given the numerous physical and psychological benefits of increased physical activity and decreased sedentary behaviour, public health strategies should include the creation and implementation of interventions that promote safe physical activity and reduce sedentary behaviour…’

The COM-B model: how to implement effective behavioural changes

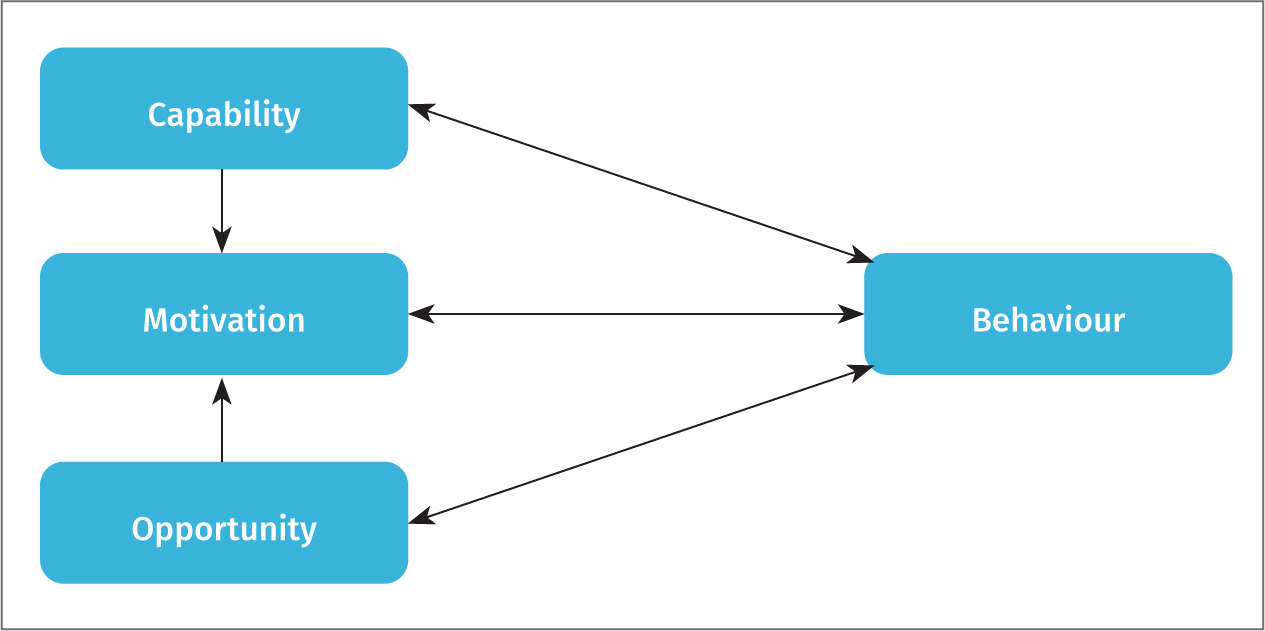

The Capability, Opportunity, Motivation Behaviour (COM-B) model (Figure 1) is widely used to identify what needs to change in order for a behavioural intervention to be effective (Michie et al, 2011). The COM-B model suggests that for a behaviour to occur, the person concerned must have the capability, and opportunity to engage in the behaviour, and be motivated to enact that behaviour. Capability relates to the individual's psychological and physical capacity to engage in the activity concerned, such as having the knowledge and skills to perform the behaviour, in this case a particular physical activity. Motivation relates to those brain processes that energise and direct behaviour, not just goals and conscious decision-making. In this case, how motivated the child is to partake in physical activity. Opportunity relates to the factors that are beyond the individual that make the behaviour possible. For example, the space to exercise or the equipment needed for a particular physical activity. There is the potential for each component of the model to influence another; for example, opportunity can influence motivation. If there is a lack of access to an open space, such as a garden, then this could reduce motivation to want to play football and partake in physical activity.

Figure 1. The COM-B model of behaviour

Figure 1. The COM-B model of behaviour

Evidence from literature reviews provide substantial support for the importance of family on children's movement behaviours and highlight the importance of the inclusion of the entire family system as a source of influence and promotion of healthy child and youth movement behaviours (Rhodes et al, 2020). Relating to the COM-B model, motivation is an important factor that can enable a particular behaviour. Therefore, it is important to focus efforts on including the entire family, and trying to find ways to encourage and motivate family members to work together, and partake in physical activities, both indoors and outdoors, rather than more typically sedentary behaviours, such as watching television indoors.

Parental anxiety can also have an impact on children's physical activity and sedentary behaviours. McCormick et al (2020) found that children of more anxious parents had fewer visits to the park and were more likely to spend more than 2 hours per day on computing or gaming compared with children of less anxious parents. It is important when thinking of strategies to increase young peoples' physical activity, to consider family members and how to make people feel comfortable and give them that feeling of capability; for example, providing ‘safe’ ways to be physically active and knowledge for how to keep safe outdoors, such as maintaining social distance.

Rundle et al (2020) point out that while increases in sedentary activity affect all children, they are likely to have the largest impact on children living in more urban areas, who do not have access to safe, accessible outdoor spaces where they can maintain social distancing. For these children, the lack of opportunity for exercising outdoors will be detrimental for the behaviour to take place. While parks and playgrounds remain open in much of the UK, Rundle et al (2020) suggest that there is widespread appreciation that it is not possible to keep the playgrounds clean and children will have difficulty maintaining social distance, leading to urban families sometimes electing not to use these spaces, exacerbating the disparity between those who can and those who cannot remain physically active outdoors. Therefore, it is important to show people other ways of staying active, to offer other opportunities for physical activity, as well as ensure the feeling of staying safe and protected.

Lambrese (2020) suggests that it is important to respond to the uncertainty of COVID-19 by developing routine and structure in a child's day, and suggested that fostering a sense of predictability at home can go a long way in helping children cope with an uncertain world. He suggests that while it is important to set aside time each school day for children to complete schoolwork, it is also vital to take appropriate breaks, and plan activities for the child or family to do during these breaks, such as doing physical activity and going outside.

McCormick et al (2020) found that in the period of April–June 2020, children's physical activity at home either increased (48.8%) or remained unchanged (32.9%). The cancellation of youth sports and activity classes have inspired programmes, coaches, independent fitness professionals and others to offer online streaming services with live or recorded sports/activity classes for youth using platforms such as Zoom, YouTube, Instagram and proprietary mobile applications (Dunton et al, 2020). This has led to there still being the capability and opportunity for children to remain active, albeit in potentially different ways to before the pandemic. This is one way of encouraging people and enabling them to be physically active at home by providing different opportunities, and it is important to advertise these to families, so that they are aware of different options of being capable and enjoying physical activity at home.

Conclusions

Research has shown that the COVID-19 pandemic has had an enormous impact on young peoples' physical activity and sedentary behaviours globally, with a decrease in overall physical activity and an increase in sedentary behaviours. It is vitally important for children to be physically active, and to prevent a new, more sedentary lifestyle being something that young people continue even once lockdown has ended. It is important that the issue of decreased physical activity is addressed, partly because of the length of time children and young people have endured this pandemic and its lockdown measures, but also because of the dangerous impact that a more sedentary lifestyle and a decrease in physical activity can have on long-term physical and psychological health.

There are a number of ways to help. Behavioural interventions should ensure that children have the capability, opportunity and motivation to carry out the behaviour of physical activity. A major factor is the inclusion of the whole family in suggestions for physical activity; helping families to come up with ways to make physical activity a part of their daily routine, as well as showing people ways of being physically active and going outside, using online platforms such as dance and high-intensity exercise classes for children on YouTube.

KEY POINTS

- Recent research has shown that COVID-19 has significantly impacted children's physical activity and sedentary behaviours.

- This has the potential to impact associated levels of physical activity and sedentary behaviour long-term; therefore, it is vital to encourage and foster physical activity in children.

- The COM-B model of behaviour can be used to identify what needs to change in order for behavioural interventions to be effective.

- One factor would be to include the whole family in suggestions for physical activity, helping families to come up with ways of making physical activity part of their daily routine, as well as showing people other ways of being physically active.

REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- Is there anything you can do in your day-to-day discussions with young people that might impact the way they view physical activity more positively?

- What methods could you use to help foster positivity towards physical activity in the families and young people you speak to?

- Have a think about the COM-B model and how particular behaviours you are trying to encourage may fit into the model.